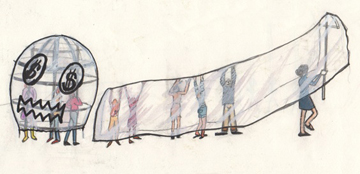

Octupy puppet graphic by Janet Owen Driggs.

On November 20, 2011, a giant octopus puppet floated up the Spring Street steps of Los Angeles City Hall. Held and maneuvered by over 40 protestors, this was the first public performance of Octupy Los Angeles, a project initiated by Performing Public Space which brings together octopus imagery, the history of the Southern Pacific Railroad, and the current Occupy movement. The puppet also performed more recently as part of Occupy the Rose Parade. Here, Teresa Carmody interviews Owen Driggs of Performing Public Space about making the puppet, animal imagery, the role of the artist-protestor, and how to make your own giant Octupy puppet.

Teresa Carmody: Why an octopus? Why now?

Owen Driggs: We first organized the octopus as a visual metaphor to help clarify the obfuscating actions of globalized monopolies—we wanted to make the corporate tentacles visible by literally winding them around the columns of L.A.’s City Hall. As the project got underway though, a second driver emerged: the relevance of the octopus—an infinitely graceful creature with an apparently distributed consciousness. So the octopus also stands as a visual metaphor for thinking about leaderless (leaderful) organization. We’d like to explore the latter idea more fully in the future, but for now the former is absorbing our attention, so I’ll answer primarily in relation to “making the corporate tentacles visible.”

For at least the past two centuries, cartoonists and writers have used octopuses to expose the workings of empire, fascism, communism, and monopoly capitalism, among others. The tentacles offer an excellent vehicle by which to describe the pervasive reach, multitudinous activity and insidious grasp of power striving for dictatorship. There is something important in the metaphor too about the alien (by which I mean the inhuman and inhumane) nature of such power operations.

More recently the metaphor has been rejuvenated by its relevance to contemporary conditions. The enormous breadth and reach of the Koch family’s right-wing network for example, coupled with their secrecy, and a fortuitous shared ‘och’ sound, has rendered “the Kochtopus” a popular study. Tony Carrk’s April 2011 study illuminates many of the brothers’ tentacles, while Zina Saunders’ 2011 animation offers a visual. A 2009 Rolling Stone article by Matt Taibbi described Goldman Sachs as “a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money.” His words spawned vampire squid imagery, spreadingly but particularly in relation to Occupy Wall Street (OWS). A recent example: On December 12 OWS people wore giant squid outfits to march in solidarity with their west coast counterparts during an action to close the ports titled “Day Without Goldman Sachs.”

With regards to Octupy though, it wasn’t so much the vampire squid and Kochtopus imagery that inspired us initially, not least because we were only peripherally aware of it before the project began. Rather, we were compelled by a very particular resonance that the octopus has for California.

In his 1901 book The Octopus: A Story of California, Frank Norris described the Southern Pacific Railroad (SPRR) as “the leviathan, with tentacles of steel clutching into the soil.” Take a look at this cartoon from 1882. It speaks to SPRR’s stranglehold on California’s commerce, its deceptive practices, its steamrolling of opposition, and its use of corruption and cronyism to grow immense wealth, land holdings, and power at the expense of the public purse and to the detriment of the public interest. The strategy and tactics certainly resonate with present day corporate practices, but SPRR is grandparent to the Kochs and Sachs of the world in more ways than one; it was in fact a (tax avoidance) lawsuit won by SPRR in 1886 that provides a major plank upon which contemporary laws regarding corporate personhood stand.

Octupy Los Angeles performance, L.A. City Hall, November 20, 2011. Photo: Teresa Carmody.

TC: How did you make the octopus? What materials did you use, how long did it take, and what was the experience of making the puppet in a public space?

OD: The process began with a public discussion about SPRR that we had with Fabian Wagmeister at Occupy LA in early October. The idea was to explore some background to contemporary sociopolitical and economic circumstances. That grew into an effort to translate the nineteenth-century cartoons into contemporary relevance, which birthed both an ongoing set of drawings and the giant puppet.

Ideas on how to make the puppet came through the AAAAAA listserv and at in-person meetings at Occupy LA. Many materials were suggested but we needed stuff that was free, abundant, light and sturdy, plus a method of construction in which people of varying ages and skill levels could participate. We settled on deconstructing plastic shopping bags and sticking them together with tape to form a kind of “fabric” for the tentacles. The head was more of a challenge until Jen Hofer introduced puppeteer Beth Peterson, who suggested using bamboo and bicycle inner tubes. Diagrams of how we made the puppet over a one-month period, plus a blog, are on the Performing Public Space website.

Making in public space in this way—as opposed to the kind of public space activity that, for example, a plein air painter undertakes—felt a little like a practical experience of the theoretical proposal that artists are advancing from the “assertion of an independent and private symbolic space” and on to the “realm of human interactions,” where meanings are constructed collectively (Nicholas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics, 2002). By this I mean that not only was the process of making visible, it was totally porous to the actions and ideas of anyone who chose to participate. In practice that meant a lot of discussing and explaining what we were doing and why, demonstrating the techniques we were using, and accommodating diverse ideas and methodologies.

Octupy Los Angeles performance, L.A. City Hall, November 20, 2011. Photo: Teresa Carmody.

TC: The use of non-human animal imagery comes with its own set of tensions. With this project, the octopus becomes both monster (greedy, strangling leviathan) and some version of a higher power (model for horizontal intelligence). Can you speak to these tensions, and to the parallels (if any) with the Occupy movement?

OD: As you say, our attraction to the octopus flows from its capacity to provide useful metaphors for both hierarchical and horizontal operations of power. The contradiction of those two states was undoubtedly a source of personal tension, for while art can accommodate ambiguity I don’t think agitprop can, not if it wants to be effective. Consequently, the question arose: are we artists or propagandists? Shall we explore the multifarious but potentially esoteric possibilities provided by an exploration of distributed consciousness? Or shall we “make the tentacles visible” in the form of a giant plastic puppet?

As you know, we plumped for the latter and, while I don’t want to romanticize the process of making or make exaggerated claims for its horizontal nature, it was a multi-person, distributed effort that created opportunities for communality and conversation. Somewhere in that mix, the tension between horizontal and vertical social relations was addressed in ways that I found satisfying as an artist.

And there’s something else here too: the octopus is a vision of controlling otherness. Its plastic, distributed, undulating form is antithetical to the Western ideal of a human being—a consolidated, conscious “I” encased by upright flesh. It’s the repulsively alien vampire squid. And yet, the puppet has no life unless we carry it. We are all inculcated and together we can drop the tentacles.

TC: At the performance on November 20, I was struck by the relationship between the puppet materials, human bodies, and voice. The puppet’s slow, slightly-jerking-yet-still graceful movement relied on a system of choreography and vocal instruction. How did you imagine human bodies interacting with the puppet during its construction? How did you choreograph the puppet performance? Were there surprises?

OD: Although we initially had visions of a ballet of tentacles winding their way around tents to meet at the octopus body, as visual artists and social practitioners we were most concerned to get the thing made. We wanted to facilitate the process of making and see what it looked like with its tentacles wrapped around City Hall before the inevitable police raid cleared us all out of Solidarity Park.

We did consider theatrical possibilities and we designed some puppet actions, but we were primarily focused on the making until about two hours before the performance. At this point it was finally possible to see how all the parts worked together, and then we had the first rehearsal. The 40 people who operated the puppet were, consequently, the ones primarily responsible for the choreography.

I still have dreams of an octopus ballet exploration of horizontalism—one in which Isadora Duncan operates tentacles as gauzy as Shirley Jones’ wedding veil from the Oklahoma! dream sequence. If there’s anyone out there who’d like to choreograph a tentacle ballet, please get in touch.

Octupy Los Angeles performance, L.A. City Hall, November 20, 2011. Photo: Teresa Carmody.

TC: What advice would you give to those who want to make their own Octupy puppet?

OD: Start collecting plastic bags. Think about ways to coordinate the puppet’s movement long before the morning of the performance. Check out our working diagrams—they may save you some time. Enjoy the process.

TC: If the LA Octupy could make one concrete political change, what would it be?

OD: We can’t answer for Octupy—it’s Matt, Beth, Chris, Jen, John, Brad, Minica, Diego, Roger, Krista, Stephanie, Noah, Lil’bit, Dayva, Regina, everyone who worked on the puppet. We can only speak for ourselves, and even then we’re afraid that we don’t have a straightforward answer. Not because there aren’t a million things we think should change, but precisely because there are a million things that need to change if we are to have a chance of flourishing fairly as a species.

Concrete suggestions mooted by OWS, OLA and others include a constitutional amendment revoking corporate personhood, the reinstatement of the Glass-Steagall Act, and a transaction tax on international financial speculation. We certainly don’t oppose any of those actions, but our collective problems are systemic and paradigmatic, they won’t be changed by a single political maneuver.

TC: Occupy LA—as both a movement and a public space—provides a stage for artistic interventions. Yet where is that line between promoting one’s art practice and promoting a political cause? How do you think artists can make overtly political work without having that work undermined by their own self-interest?

OD: First, we’d like to say that Octupy is totally self-interested. Our self-interest and the sociopolitical and economic changes we want our work to support are completely entwined. Can one be separated from another when the quality and future viability of human life depend on change?

Second, regarding the ways in which artists navigate promoting a political agenda and garnering career and monetary gains—we’re back in the tensions between parts and whole, individual and collective, that we mentioned earlier. We polarized the roles of artist and propagandist and separated the aesthetic and social functions of art in order to name those tensions, but the divisions are nowhere near that clear-cut and oppositional. They are, rather, points on a spectrum. We don’t think there is “a line.”

TC: What’s next? Will the Octupy perform again?

OD: On January 2, 2012 Octupy participated in Occupy the Rose Parade. For this outing, we were part of a larger human float that focused on an anti-corporate finance message. To sharpen that meaning we made puppet “accessories” for Octupy that included a huge hand snatching money from the pocket of the 99%, a giant hundred dollar bill to be stuffed into a ballot box, and a hammer, with which a tentacle tried to smash a picket-fenced house.

The puppet—which the LA Weekly described as “70 feet of Awesome” (we particularly liked that one)—stimulated a lot of media attention, including international coverage, in the run up to the parade. Not surprisingly there was a lack of live coverage on the day, a circumstance that itself drew comment from the LA Times and the LA Weekly. In all likelihood Octupy will next emerge to support the May 1st General Strike.

Teresa Carmody is a writer and the co-director of Les Figues Press.

Since 2007 Janet Owen and Matthew Driggs have worked as the collective identity “Owen Driggs.” Together they operate Performing Public Space, a multifaceted initiative that explores and supports ways in which citizen artists activate public space.

Pingback: #OccupyArt21 | AAAAAA

Pingback: From the Voice of the People to the People of the Voice | Art21 Blog