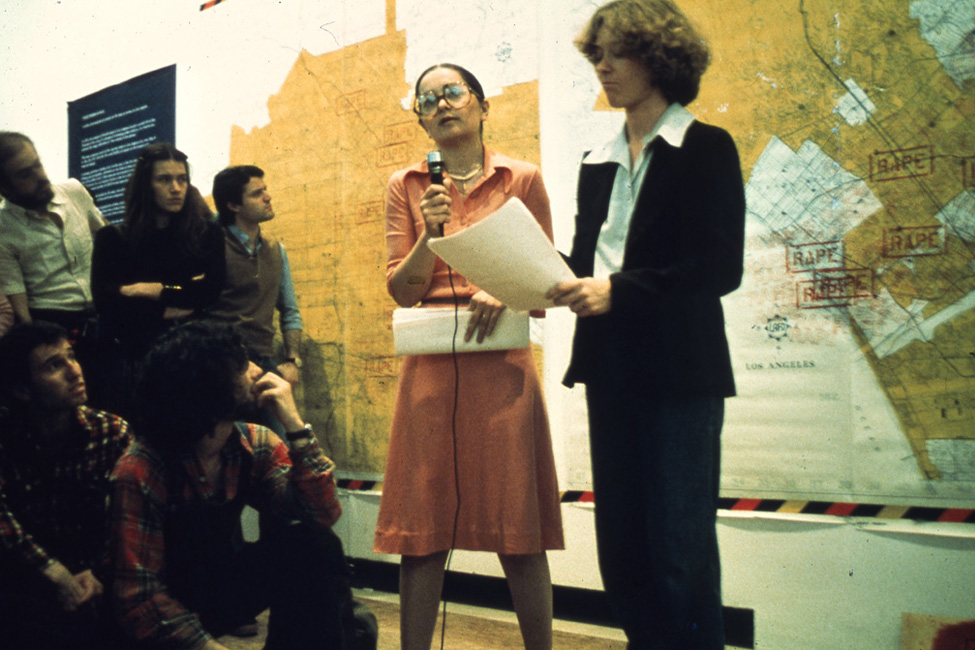

Today, Thursday, January 12, artist Suzanne Lacy will meet with Los Angeles Mayor Villaraigosa at the Los Angeles police department about ending rape in Los Angeles. An official from the police’s rape treatment center will be there, as will members of the media, and the meeting will launch Three Weeks in January, a project in which Lacy will, every day, document the rapes reported the day before on a map of L.A. hung outside the L.A. police’s Deaton Auditorium. Volunteers and students will help her do this, as they did thirty-five years ago, when Lacy launched Three Weeks in May, hanging her original rape map outside L.A.’s City Hall and updating it daily, even going out into the city and marking points on the sidewalk near where rapes had happened.

No one would argue Lacy’s status as a “real” artist; her work belongs to major museum collections, she was part of the original Judy-Chicago-helmed Feminist Art Program and she writes well about “performance” and “publics” (words only those versed in theory pair liberally). And that artists take on political messages is, of course, old news. But somehow, rape and sexual violence seem to have become a special duty for contemporary female artists, and one still conventionally gendered. Sure, the [male] mayor will be at the launch today, but a woman will be helming this campaign and the majority of participants will be women in a project that partly feels like a clean-up effort, a targeting then washing away of a scourge that still particularly affects female lives.

Women artists always participated in the frequent, on-campus Take Back the Night events, aimed at sexual violence awareness; when I was in college and grad school, I did too–it felt almost obligatory. They designed the posters and T-shirts or passed out fliers. At the last such event I attended, clotheslines were used to hang posters, and, unsurprisingly, the clotheslines very clearly connoted “cleaning up.”

I am thinking about clotheslines this week, in part because of Lacy’s Three Weeks in January clean-up, but also because I have seen or read about them in two historical L.A. artworks recently.

In Ericka Beckman’s The Broken Rule, a film made in 1976 and screened at MOCA on January 8, clotheslines appear repeatedly. In fact, the film opens with them: you see a woman in a sunny backyard hanging items slowly, but she keeps peeking over the billowing fabric to, we are made to understand, stare at a man nearby, who is also hanging clothes on a clothesline, but doing so in a competitive way, as if battling a Rubrik’s Cube. Soon, the woman disappears and then we see only men, two sets of them, with laundry baskets. One at a time, the men rush toward the clotheslines and hang the contents of their baskets, then rush back to hand off the basket to the next in line, who returns to the clothesline, pulls down the clothing, then hangs it again. So, in the hands of men, cleanliness becomes beside the point and competition takes over. Clotheslines become part of “the game” (which, in Beckman’s film, also includes relays with brief cases and top hats).

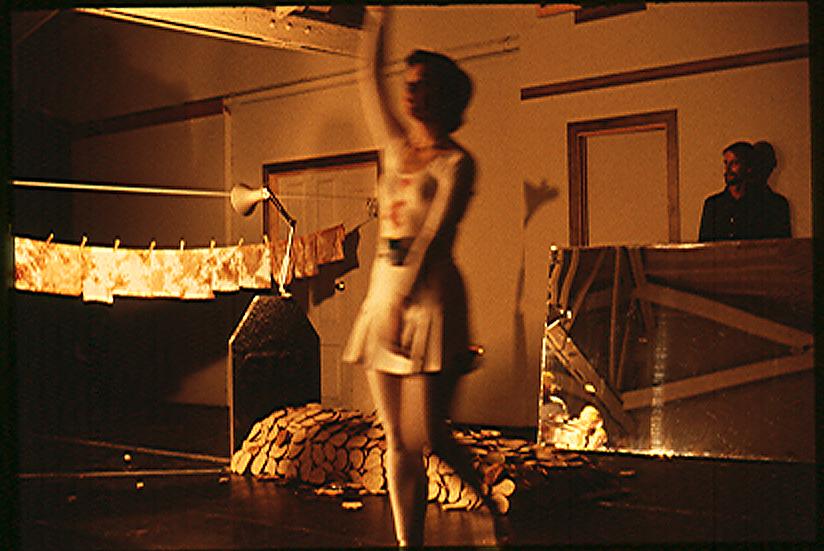

Because artist Liz Glynn is curating a series of re-performances that start this month, called Spirit Resurrection after the 1980 Public Spirit performance art festival, artist Barry Markowitz will be performing on January 14 at Human Resources L.A. The performance he did in 1980, called Think About it Susan, began in darkness with the hanging of two mylar clotheslines. An absurdest surgery plays out, where the artist is the one on the operating table, handing bloody rags to his mother as they enumerate (“I want to keep these,” he says, and the surgeon replies, “You know, these aren’t worth much without a signature”). His mother hangs them on the lines, which eventually are hung with bloody rags and not the least bit clean.

These two examples, by Beckman and Markowitz, are subversions of the clothesline symbol. In The Broken Rule, the clothesline helps Beckman comically address power structures that define gender. In Think about it Susan, they’re just one more subversion among many. However, perhaps the most compelling example of clothesline art, the installation Lintels by Gabriel Orozco (Season 2), is vague, minimal, and gray. Orozco draped lint — made up of hair, skin, dies, fabric — collected from New York laundry mats over clotheslines hung high across an otherwise empty Tate Gallery in 2001. He de-gendered the clothesline completely, and even pulled it out of the language of domesticity, instead making the conversation about what’s left behind and overlooked.

It seems that Three Weeks in January, though certainly gendered, really has that same goal: to address what’s often criminally overlooked, which is an aim art is particularly good at facilitating.

Pingback: Looking at Los Angeles | Andrea Fraser’s Men on the Line | Art21 Blog