Like a punch in the solar plexus of fine art: that’s what it felt like six years ago when I stumbled upon the piece Museum Meltdown by the Swedish artists Palle Torsson and Tobias Bernstrup. Museum Meltdown is a series of three artistically modified videogames based on reconstructions of famous art museums. The first piece was created in 1996, when both artists were still studying at art school. Museum Meltdown #1 is a reconstruction of the Arken Museum of Modern Art outside Copenhagen–with help from the classic videogame Duke Nukem. In a new level added to Museum Meltdown, you can run around the museum, shoot at monsters, and destroy art. I found the combination of videogames and art, popular culture and fine art, violence and destruction in contrast to the typical silence of the exhibition hall fascinating. The fact that there has been relatively little written about videogames and art is the main reason that I have followed this path for the last six years.

But I must confess that I myself am not a gamer. I played videogames when I was young, as many in my generation did, but as an adult I don’t really have time and I find most of the games boring. The concepts haven’t changed since I was young: shoot, kill, hit, jump, run, collect and solve puzzles. The graphics and sound qualities are now better of course, but the games themselves usually aren’t. Instead, I prefer to investigate and write about how artists are using videogames to create art.

When I grew up in the 1980s, videogames and heavy metal music were considered by adults and established society to be low and “dangerous” forms of popular culture. For me, artworks like Museum Meltdown were a revelation: this new creative and artistic medium that had for so long been looked down upon, even despised by the art world, was now being exhibited in established art museums. Videogames were finally being taken seriously, and they were kicking the art world’s ass. You could now enter an art museum with a gun and blow art history to pieces–virtually, anyway. In some sense, works like Museum Meltdown remind me of the 1909 Futurist Manifesto which declared: “We want to demolish museums and libraries.” With this videogame, you could do so, at least with a virtual copy of the art museum.

So when did artists start to use videogames to create art? You can find the prehistory of Game Art in the demoscene, which was developed during the eighties when different hacker and cracker groups created crack intros to videogames to which they had “cracked” the copyright protection. To show the world who had cracked the game, and to show what excellent programmers they were, they created graphic and music intros which tried to squeeze the most advanced effects out of their processors. These creative and artistic short demos were the first attempt to combine videogames with artistic expression.

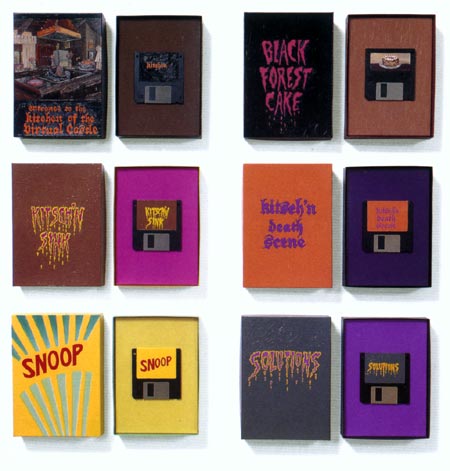

Suzanne Treister. "SOFTWARE: Would you recognise a Virtual Paradise," 1993-4. A series of 36 imaginary software packages, oil paint and/or mixed media on cardboard boxes and floppy disks. Dimensions of each diptych: 22.5 x 16 x 4 cm (x 2).

Two pioneers in the field that must also be mentioned are both women, working within a genre that in the beginning was largely dominated by men. In Jane Veeder’s “VIZGAME” (1985), the player can create his or her own real-time animation. The program was created by Jane Veeder in 1985 and runs on a Datamax UV-1 Graphics System. Also, Suzanne Treister in the late eighties painted game-inspired paintings, and in the nineties created a series of fictional videogame stills using Amiga’s Deluxe Paint II.

But the breakthrough for Game Art as a new art form was established in 1995 when the Austrian artist Orhan Kipcak exhibited ArsDoom at Ars Electronica in Linz, Austria. The artwork was a modified copy of the game Doom II with a reconstruction of the Brucknerhaus‘ exhibition hall. During the first years of Game Art most works set about modifying famous commercial First Person Shooter (FPS) games like Doom, Unreal, and Quake, which had tools which made it easy for users to design new levels and thus modify the games. I’ve identified a particular genre of Game Art that I call First Museum Shooters. As in the examples of ArsDoom and Museum Meltdown, First Museum Shooters are reconstructions of famous exhibition spaces were the player can run around and shoot at monsters and, in the process, destroy the exhibited art. You can find a few more example of this type of work in an article I wrote for Hz-Journal, and if you want to read more about the pioneers of Game Art, you can read some of the interviews I have done with key artists in the interview series Game Art Worlds: The Early Years.

Today, Game Art has become a broad category that includes Art Games, installations, machinima, paintings and sculpture. If I were to try and define Game Art, I would say that the definition you find in the book GameScenes: Art in the Age of Videogames (Johan & Levi, 2006), edited by Matteo Bittanti and Domenico Quaranta, is still the best: “Game Art is any art in which digital games played a significant role in the creation, production, and/or display of the artwork. The resulting artwork can exist as a game, painting, photography, sound, animation, video, performance or gallery installation.”

During my two weeks guest blogging for Art 21, I will give you further examples of what Game Art can be, along with some examples of another interest of mine: Black Metal in contemporary art.

Pingback: The Unholy Trinity of Postmodern Architects, Black Metal, and Holy Minimalism | Art21 Blog

Pingback: The Unholy Trinity of Postmodern Architects, Black Metal, and Holy Minimalism | Benjamin Phillips