This month, I had the pleasure of speaking with San Francisco-based artist Mauricio Ancalmo. It is difficult to label Mauricio’s practice, as his work includes sculptural installations, performance, video and works on paper. The concept that Mauricio’s works all seem to speak to is the relationship between humans and machines. His work A Lover’s Discourse is currently featured in the SFMOMA 2010 SECA Art Award exhibition, and he has a solo show at Eli Ridgway Gallery in San Francisco. His work, Dualing Pianos: Agapé Agape in D Minor was featured prominently at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts triennial, Bay Area Now 6 in 2011.

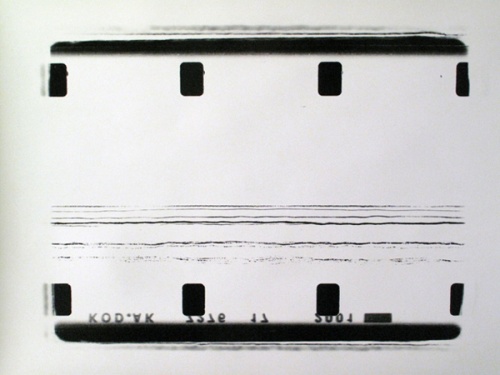

The centerpiece at Eli Ridgway Gallery is a sculptural installation, Monolithoscope, which consists of a 16mm film projector, a turntable and record, stereo amplifiers and speakers, a bio chart reader, and black film leader that runs through these connected devices. On the projected film, one can see a series of moving white lines that are created by the needle of the bio chart reader as it interprets the sound vibrations. From the scratched film, Mauricio created a series of silver gelatin prints.

Descriptions and videos of Mauricio’s work can be found on the Eli Ridgway Gallery website.

A voracious reader and an academic, Mauricio’s practice is heavily informed by texts of all kinds, from magazine articles to philosophy to textbooks. The following is a list of books that Mauricio Ancalmo has found particularly influential and thought-provoking:

Henri Bergson, Laughter, trans. Cloudesley Brereton (1913)

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, trans. Brian Massumi (1988)

Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, ed. & trans. Hoare/Smith (1971)

John Boslough, Masters of Time (1992)

Ritter/Kochel/Miller, Process Geomorphology (1978)

Kelly Huang: You mentioned previously to me that “books and readings all inform each other in some way or another,” and that you have found a thread in these readings, as well. In researching and reading through your list, the two threads for me were that of repetition and the second is the notion of the human versus the mechanical. I am curious to know what those threads are for you and if these were the same for you.

Mauricio Ancalmo: Definitely. With repetition in the book Laughter, the notion of machinery really came to mind. In the 20th century it was a big deal, and in the 19th century before it, there were always these analogies of the steam engine to the human body, and of course nowadays things are digital and the references are to the digital. But to me—digital or analog—it is still a machine and the way we process things in life can be very machine-like. For instance, the machinery that society has dictated what is and is not okay. The idea of machinery is not old. It is still something I think is still very present. I find it in my everyday, my natural discriminations toward things. Then, I ask myself why am I thinking this way? Maybe it is because I was brought up this way or told to do that—and once again the machine kicks in.

In my work, a lot of the installation pieces came from the idea of making instruments. It is something very simple like this: I wanted to make instruments, and I started to make instruments, and then I thought about how to remove myself from playing these instruments. As I was performing, I realized people were more interested in the performer than the instrument. And to me, I was more interested in the instrument. As these installations started becoming autonomous, I started thinking about the machinery that happens, then I started kicking in this idea of loops, which goes back to some of these books: Henri Bergson, Gilles Deleuze, Antonio Gramsci.

At a certain point, I want to ask the viewers, what is or isn’t a given anymore? For instance, with art, just because it is a landscape or pretty colors, it is art? You always run into this—what is and what isn’t. I still like this idea of pointing out something that might be obvious or looks seemingly simple, but once you start digging and dissecting, you realize how complicated it really is and how every little part has to do with another part.

With Process Geomorphology, I love this idea of erosion and geology. When I started working on that, I realized that part of this daily grind is this erosion that happens. Where I might have known something to be perfect in my childhood, now it may not be so perfect, per se, if I compare it. I have a past reference and a now reference. In reality, it is what it is and it is a process of geomorphology. Things change but eventually they come back. There is an ebb and flow to life—it is not so concrete. There is not a given timeline for everything. That goes along with my work. The timelines are very interesting. I try to bend those timelines, as in my 24-hour film, Lux Luthor. Films to me always have this beginning and end, but why? Technically, it still carries on. For instance, if I watch a movie, I will think of it years later if it is really good, so technically the plot is still going on and who knows what I might think of it later on.

KH: Right. At various points in your life, you think about it differently. It applies to you in a different way.

MA: Exactly. I will see this today and I will see it tomorrow, and it will be two different videos. I will never see the same thing twice. I feel it is equally the same when looking at art. With this video, I thought it would be good to explore the idea of no beginning and no end, with a timeline that becomes warped.

Mauricio Ancalmo. "Monolithoscope," 2011. Inverted 16mm film strip. Photo courtesy the artist and Eli Ridgway Gallery.

KH: You have some beautiful silver gelatin prints in the gallery now, and I think they read as abstract landscapes. I thought about how Process Geomorphology might relate to how you think about a landscape, abstraction or the erosion of the film as the needle scrapes it. Has this text influenced the way you think about the formation of these abstractions?

MA: Definitely. I have always been interested in landscapes and wondering how things came to be. There was a point in my life where I asked, how did these things actually come to form? Once again, timelines start crisscrossing and I see things as being intertwined. I really love the idea of landscapes and how they form. It is really interesting how they inspire us—you can say, oh that’s beautiful, but you can also look at a landscape and say that’s disgusting or horrible. It depends on the landscapes, I guess, but the main idea for the works I was doing was somehow to interpret these other types of landscapes that happen on surfaces or happen from installations I was experimenting with. For example, Monolithoscope. When I did my first experiment with the piece and saw the lines being scratched on the film by the bio chart reader, I all of a sudden had this weird sensation that there was something very geologic about this piece. It had time elements, erosion, surface, the loop happenings, and this bellowing sound coming out from the machine. When I took just a little section of the film strip and looked at it really close, it resembled a landscape—a horizon line or ocean waves. I blew it up and made it giant just to see it at our scale. When I started doing that, I started treating others in the same way. Mainly, I realized that there are other ways to experience these installations. Those artworks came from being able to connect the dots with the books I had been reading and putting all of these experiments together.

KH: The writings of Gilles Deleuze seem to influence your practice in a few ways: his text is used directly as media in Dualing Pianos: Agapé Agape in D Minor and it seems to me that his theories of the rhizomatic play into your work. Can you speak to how Deleuze’s ideas of language, music and performance have influenced your work?

MA: It is always tough to say what the influence was. When you pick up a book, it either talks to you and it is in your language, or it is not. The minute I picked up Deleuze, once again just like the Bergson, I was like, “wow” I wish I had known this person, and yet I am getting to know this person through the book. There are some thoughts that I have had, but before reading some of these books, I had trouble validating them in some way. But that guy [Deleuze], he goes off and goes on so many tangents beyond what my brain even thought was possible. I see it as almost poetry. There are always striations in his writings—in paragraphs and texts. I have been able to link words systematically through his writing.

KH: There is a parallelism in his writing style.

MA: Yes, it is almost like a hidden subtext that he has purposely put into his writings. It takes a little bit of digging through it and re-reading it to find them. Some of them are just way over my head, obviously, and some of them he made them purposefully unattainable. For that reason, some labeled him as a crazy person because he was able to not have these limitations we have. I see him as one of these people who was able to break the machinery of not only his own thinking, but definitely of social norms.