I first met the artist, writer, and activist Ted Kerr during the summer of 2008 when we were both interns at Visual AIDS. He was standing outside the West 26th Street building with the executive director, Amy Sadao. My memory of the day is a sweltering bleached blue; Ted was wearing bright red pants and a striped shirt. I think he was smiling and waving, or the grin on his face registered as a giddy wave. I bring up my very first impression of Ted because he is perhaps the most hopeful person I know and, for me, that sunny image somehow encapsulates his hopefulness.

His writing and collages strongly reflect this hopefulness not only in their optimism, but also in the way he poses questions about everyday things and events in light of queerness, AIDS, and collectivity. They’re not easy questions to consider, but in posing them, Ted is inviting others to ask more questions, to bring seemingly disparate ideas together, out of which some new space for thinking, art-making, and collective action might arise. Ted’s always looking to have a conversation. His collages are like snippets of dialog between images and text he has gleaned from television, museum exhibitions, and song lyrics. Rihanna’s We Found Love, a portrait of a snowy Walt Whitman, and Occupy Wall Street all make their way into his pictures and reveal their connectedness.

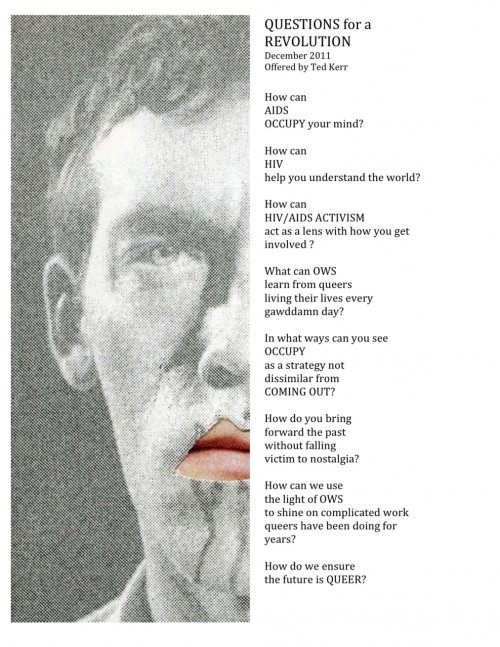

In Questions for a Revolution, Ted generates a list of suggestions and inquiries that relate the Occupy movement to the experience of being queer. Ted presented these questions at DYKE CHECK!, but he has also shared them on his blog, along with an invitation to readers to chime in with their own ideas. In that post, his questions are positioned next to a reprinted portrait of David Wojnarowicz, whose once-sewn lips have now been collaged with a new mouth. This is about undoing silence through a critical dialog with others. (As Foucault says in The History of Sexuality: An Introduction, “There is not one but many silences.” There’s the silence that the State imposes, but there is also our silence: the silence of the closet, our silence toward the State’s silencing, and our silence toward each other).

Channeling Wojnarowicz’s image and his ideas for unraveling and fighting against what the late artist called the “pre-invented world” of normativity, passive acceptance, and indifference toward AIDS, Ted asks eight questions. Among them are:

“How can AIDS OCCUPY your mind?”

and “What can [Occupy Wall Street] learn from queers living their lives every gawddamn day?”

and “In what ways can you see OCCUPY as not dissimilar from COMING OUT?”

What do the answers to these questions look like? And maybe before considering them, what would it mean for us, collectively and as individuals, and for the spaces and relations we inhabit, to be able to think about and discuss these questions?

In light of Ted’s questions, I think of being queer as being indelibly marked by the initial feeling of sexual difference, but instead of this difference driving queer people apart, it brings us together. Queerness is difficult, not because in being queer you are confined to yourself. On the contrary, being queer pushes you forward, beside yourself, and makes you see and consider what it means to be part of a larger social group, whose members—like you—share the responsibility of relating and empathizing with others, a responsibility that difference brings to bear on the singular self.

Ted’s work, with its social and utopic aspirations, reminds me of the artist/activist collective Gran Fury. The group emerged in 1988, made up of artists and activists who had previously worked with ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) on the New Museum installation, Let the Record Show… (1987). In the late 80s and early 90s, they created public interventions in the form of posters and bus panels that mimicked the clean, look-at-me aesthetic of brand-name advertisements in order to put AIDS in the visual field of the public. Among these text-based agitprops were Read My Lips (1988) and Kissing Doesn’t Kill (1989-1990). The former was used to incite public kiss-ins; it was wheat-pasted on building facades and printed on t-shirts worn by protestors during rallies. The latter appeared on buses and train panels. Both projects sought to change public perception about AIDS, to combat homophobia and indifference by engaging people at street level. (An exhibition of Gran Fury’s works will open on January 31 at 80WSE Gallery).

Ted’s Questions for a Revolution parallels the four questions in Gran Fury’s 1993 poster, Untitled:

Do you resent people with AIDS?

Do you trust HIV-negatives?

Have you given up hope for a cure?

When was the last time you cried?

In a 2003 Artforum interview with the critic Douglas Crimp, Gran Fury’s Loring McAlpin explained the motive for the Untitled questions: “[We] were addressing a different audience. It was really directed toward our own community. We were trying to acknowledge something but not judge it, to ask, ‘What’s happening now? Where did our anger go? What are we going to do?’”

As a young queer person, I think about my generation’s place in this history and how AIDS has shaped queerness beyond the 80s and 90s. I think about Ted’s question, “How do you bring forward the past without falling victim to nostalgia?” Perhaps the best response I have to this question is to pose my own questions: How can we see ourselves—queer persons born in the 80s and later—as members of that community which McAlpin speaks about? What is our individual and collective relationship to this past? What role does this shared history play in our personal and social coming-out?

Pingback: At the Dinner Table… | Art21 Blog