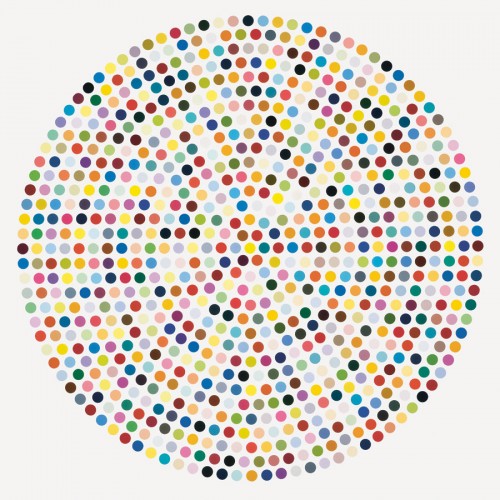

Damien Hirst. “Zirconyl Chloride,” 2008. Household gloss on canvas. 84 inches diameter. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery. © Damien Hirst/ Science Ltd, 2012. Photography Prudence Cuming Associates.

“I was always a colorist, I’ve always had a phenomenal love of color… I mean, I just move color around on its own. So that’s where the […] paintings came from—to create that structure to do those colors, and do nothing. I suddenly got what I wanted. It was just a way of pinning down the joy of color.”

If I told you that the great French colorist Henri Matisse uttered the above words would you be surprised? Now what if I told you that these are in fact the words of Damien Hirst, the enfant terrible of the late 20th century best known for his bisected animals submerged in formaldehyde, cabinets filled with medical supplies and an installation consisting of live maggots and a severed cow’s head? The paintings to which Hirst is alluding in the above quotation are his Spot Paintings, a series of over 300 paintings currently being exhibited at Gagosian Gallery’s eleven locations in eight countries across three continents. What surprised me more than Hirst proclaiming to be a colorist in the epigraph of the press release for “The Complete Spot Paintings 1986-2011” was that, after viewing those works on view in Gagosian’s New York spaces, I could not help but appreciate the way in which the Spot Paintings resonate with Matisse’s canvases. Let me connect those dots, if you will.

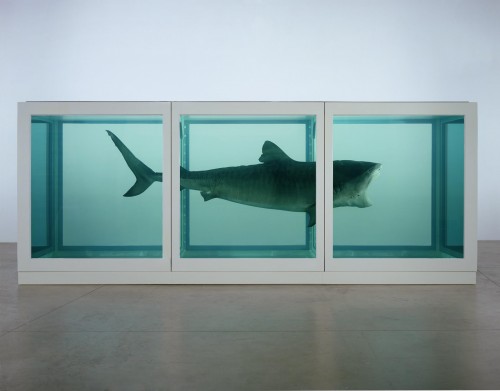

Hirst came of age in the late 1980s as a leading figure of the Young British Artists group, emerging onto the contemporary scene in London through a series of audacious exhibitions highlighted by the 1988 Freeze show, a now legendary exhibition curated by Hirst while he was still a student at Goldsmith’s College. Advertising mogul Charles Saatchi attended the show, which was staged in an abandoned space in the London Docklands, and by 1991 had offered to fund Hirst’s art production. In short order Hirst produced arguably the most iconic work of the 1990s: The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991). Hirst would go on to win the prestigious Turner Prize in 1995 and before long, as his art morphed into a full-blown brand, become the poster child for the dovetailing of art and corporate capitalism.

Damien Hirst. “The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living,” 1991. Tiger shark, glass, steel and formaldehyde, 7 x 17 x 7 feet. Courtesy Damien Hirst and Hirst Holdings/Tate Modern. © Damien Hirst/ Science Ltd, 2012. Photography Prudence Cuming Associates.

It is difficult not to view this dovetailing as the structuring principle behind Gagosian’s simultaneous global presentation of Hirst’s Spot Paintings series, which except for a few canvases were made by assistants and have the unmistakable character of impersonal, assembly-line production. Indeed, the seamless merging of art into commerce is made plain in the pop-up store located on Madison Avenue adjacent to Gagosian’s uptown gallery and the retail store found inside the 24th street gallery space, which are stocked with clocks, tee shirts, mugs, iron-ons and limited-edition tchotchkes emblazoned with Hirst’s signature colored spots. These collectables are produced by Other Criteria, a publishing and merchandising company founded by Hirst.

These stores represent but one instance among many of Hirst’s innovative and at times controversial branding of himself and his art (in Hirst’s defense many of his commercial ventures—including Other Criteria—have been founded to promote emerging and established artists). But it isn’t fair to say that, as some contend, Hirst’s art operates exclusively according to the rules and logic of capital. After all, his work has consistently revealed a conceptual indebtedness to and concern with art history and pictorial tradition, resulting in an oeuvre that has in one way or another always been about Art itself. Early works such as Trinity, Mother and Child Divided and Away From the Flock teem with art historical reference and take up the timeless artistic themes of spirituality, mortality and death.

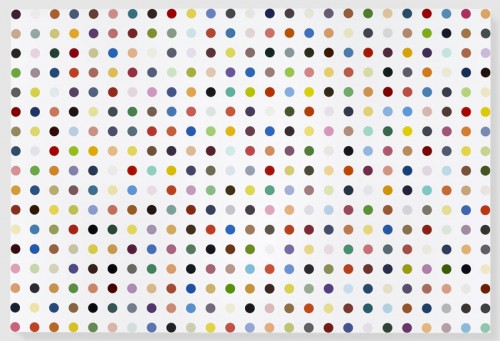

Damien Hirst. “Isonicotinic Acid Ethyl Ester,” 2010–11. Household gloss on canvas, 99 x 147 inches. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery. © Damien Hirst/ Science Ltd, 2012. Photography Prudence Cuming Associates.

To my mind, Hirst’s Spot Paintings are no different in their engagement with art history, as these pulsating canvases of color—ranging from dense fields of tiny dots to a few spare circles isolated against an expanse of white—call to mind Georges Seurat, Hans Hoffmann, Kenneth Noland, Frank Stella, Gerhard Richter, and many more. Even the title of Hirst’s publishing and merchandise company, Other Criteria, offers an oblique art historical reference—an allusion to the late great Leo Steinberg’s celebrated 1972 book Other Criteria: Confrontations with Twentieth-Century Art, which brilliantly and radically reconsidered the significance of Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg and other artists. And it is this reference by Hirst to Leo Steinberg that brings me back to Matisse, and connects the dots between the great French colorist and Hirst’s Spot Paintings.

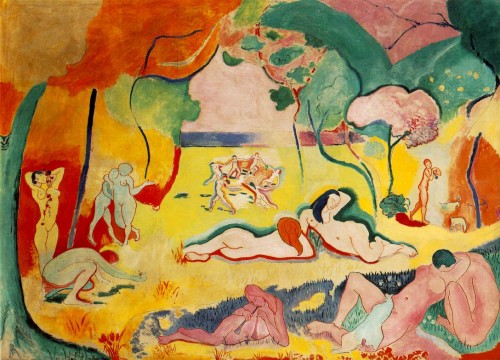

Henri Matisse. “Le bonheur de vivre (The Joy of Life),” 1905-06. Oil on canvas. 69 1/8 x 94 7/8 in. © Damien Hirst/ Science Ltd, 2012. Photography Prudence Cuming Associates.

At one point in Other Criteria Steinberg describes looking at Matisse’s famous painting The Joy of Life (1905-06) in the following terms: “it is somewhat like watching a stone drop into water: your eye follows the expanding circles, and it takes a deliberate, almost perverse, effort of will to keep focusing on the point of first impact—perhaps because it is so unrewarding.”[1] Here Steinberg conveys the almost dizzying effect of looking at Matisse’s all-over fields of pulsating color, which art historian Hal Foster Yve Alain Bois would later identify (in a 1994 essay fittingly titled “On Matisse: The Blinding: For Leo Steinberg”) as the radical core of Matisse’s pictorial program beginning around 1906.

By Foster’s account, Matisse’s major breakthrough in the use of color in the construction of pictorial space was the realization, penned in the artist’s notes around 1905, that “a square centimeter of blue is not as blue as a square meter of the same blue.”[2] For Foster, Matisse’s revelation resulted in the democratization of every point on the canvas, as a color’s quality—its value—was now seen to depend on its surface area, and thus became inextricably tied to every other plane of color on the canvas. As Foster puts it, Matisse realized that “[a painting’s harmony] involves the whole surface of the painting, and results from the sum of colored surfaces opposed in it.”[3] Increasingly, Matisse’s innovative use of color as the structuring principle of his art resulted in dynamic canvases without stabilizing centers, “all-over” compositions that mobilize the viewer’s gaze while denying the solace of coherent form and spatial relations. Foster concludes that the result of Matisse’s radical program was an intense decentering of viewing experience, a “blinding” of conventional ways of seeing.

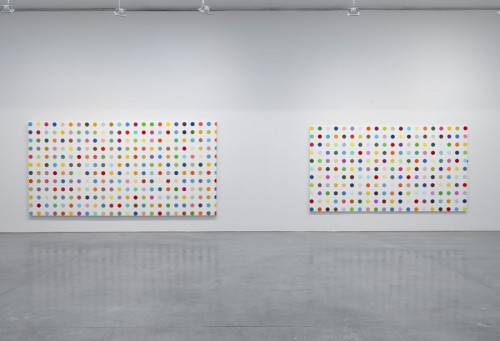

Damien Hirst. “The Complete Spot Paintings 1986-2011.” Partial installation view. Courtesy Rob Mckeever and Gagosian Gallery. © Damien Hirst/ Science Ltd, 2012. Photography Prudence Cuming Associates.

If Steinberg and Foster both intuitively sensed this decentering as the keystone of Matisse’s radical invention, I suspect that Hirst’s spot paintings, especially when able to be viewed en masse as they are now, effect a similar visual experience. It is worth revisiting Hirst’s own words: “I was always a colorist, I’ve always had a phenomenal love of color… I mean, I just move color around on its own. So that’s where the spot paintings came from—to create that structure to do those colors, and do nothing. I suddenly got what I wanted. It was just a way of pinning down the joy of color [emphasis added].”

When confronted with room after room of Hirst’s colored spots ranging in diameter from a few millimeters to sixty inches, at times displayed in densely packed grids made up of thousands of dots and at others consisting of but a handful or even just a single dot, there is a sort of decentering of vision—a blinding, to use Foster’s term—that begins to take place. Like a Matisse canvas, the collisions of pure color that occur between adjacent spots on Hirst’s canvases set the viewer’s gaze in motion. In Hirst’s Spot Paintings, the value of each individual “spot” of pure, unmodulated color becomes determined by the different color values of the spots adjacent to it. This is to say that as one gazes at any given Spot Painting, each color on the canvas enters into a state of ongoing formulation and reformulation, activated by its relation to the other colored spots and the whiteness of the support surrounding it. The construction of pictorial space becomes wholly dependent on the surface relations among these planes of pure color.

Damien Hirst. “The Complete Spot Paintings 1986-2011.” Partial installation view. Courtesy Rob Mckeever and Gagosian Gallery. © Damien Hirst/ Science Ltd, 2012. Photography Prudence Cuming Associates.

Like a Matisse canvas, our eyes are obliged to wander across the entire surface of a Hirst painting, settling nowhere in particular. Hirst’s colored spots work collectively and simultaneously to set the eye in motion, becoming not an appreciation of individual colors as one might expect but rather an experience of the all-over. Each individual spot merely becomes Steinberg’s stone hitting the water and reverberating outward. It is a startlingly harmonious expansion that extends beyond the boundaries of each individual canvas to other Spot Paintings on adjacent walls and in adjoining rooms, as each colored circle begins to take on a different value when viewed in relation to the others within one’s field of vision. Even canvases composed of just a lone colored spot are not immune to this dispersal and decentering, as they too succumb to this circuit of visual exchange with its neighbors.

Damien Hirst. “The Complete Spot Paintings 1986-2011.” Partial installation view. Courtesy Rob Mckeever and Gagosian Gallery. © Damien Hirst/ Science Ltd, 2012. Photography Prudence Cuming Associates.

Like Matisse’s greatest canvases, Hirst’s spot paintings become a simultaneously mesmerizing and decentering viewing experience of, to use Hirst’s own words, “the joy of color.” Indeed, Gagosian Gallery’s ambitious exhibition stands as convincing, if admittedly surprising evidence that Damien Hirst is indeed an extraordinary colorist.

“The Complete Spot Paintings 1986-2011” is on view at Gagosian Gallery in New York until February 18, 2012.

Pingback: On View Now | Damien Hirst’s Spot Paintings and the “Joy of Color” « Color Workshop

Pingback: The Art21 Blog’s Most-Viewed Posts of 2012 | Art21 Blog

Pingback: EX02 – Pesquisa | inventory in [progress]