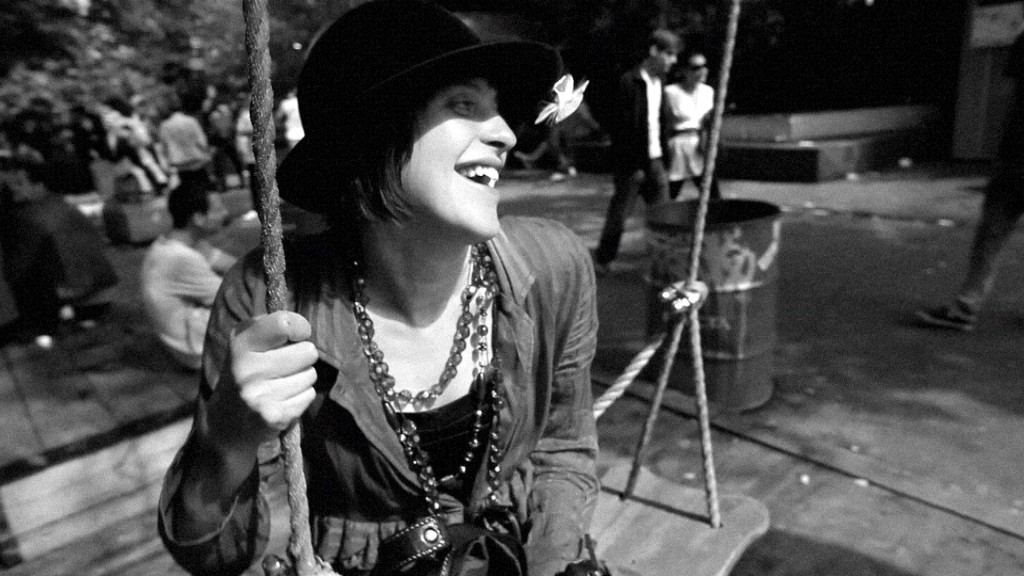

Film still from "Anna Pavlova" (2011), directed by Theo Solnik. Courtesy the artist.

Anna Pavlova Lives in Berlin depicts the poetic and aggressive “Russian party queen,” of the same iconic name. Replete with club door fights, looming graffiti, pill exchanges and techno trances, it could have been a petty and self-aggrandizing glimpse into the Berlin party scene. But Theo Solnik, the film’s Brazilian director who, this year, received the National Gallery’s first ever Prize for Young Film Art, avoids this limited vision, instead offering us a nuanced portrait of Anna Pavlova as she navigates the strata of her constructed and intentionally hazy worlds.

I stumbled into Solnik’s 78 minute film as I was touring the exhibitions at the Hamburger Bahnhof and was surprised at my willingness to stay, even with an attention span normally attuned to 10 minute video projections. Watching a feature-length film in a contemporary art museum highlights the divide between the worlds of film and “high art” (exasperated quotations), a contextual question especially apt as the city is taken over this week by the Transmediale, swiftly followed by the Berlinale.

Anna Pavlova was shot in the summer of 2009 on the (then new) Cannon 5D, an instrument allowing film students like Solnik greater cinematic clarity. Against a backdrop of questionable clubs and serene German lakes, we follow Anna Pavlova as she smokes, laughs maniacally and gives dubious soliloquies on her own nobility and greatness:

“I am noble, but at the same time I am nobody.”

“I don’t walk down the street, I swim.”

A lot of her statements are hyperbolic and at times, patently untrue; like the discussion of an impending 7,000 euro arranged marriage or the dogged insistence that she will pay a doorman back if she can only go find her friends first.

The film’s rich black and white hues give it a kind of Godard loveliness, a comparison enhanced by Solnik’s close-ups and the physical beauty of Anna. The objectivity of his camera work is called into question when one stranger asks, “Are you in love with her?” The viewers might ask the same, as Solnik tenderly lingers on his subject’s face in moments of repose.

Although she usually has a “crew” attached, Solnik doesn’t depict them at any length, instead focusing on Anna, a choice he says reflects his desire to “be honest.” Anna’s dynamism is such that people orbit around her, with her reciting monologues rather than conducting conversations.

Solnik met Anna Pavlova at the legendary (now sadly redone) Bar 25, asking first to photograph her before eventually turning to film. There is a stillness and palpable intimacy between them that brings to mind the “deviant” photographs of Diane Arbus or Nan Goldin. At other times, Solnik’s lens seems interested in the alchemical idea of culling the “essence” of a person through imagined form.

It makes sense that Solnik admires the nuance of Frederick Wiseman’s films, which, while pointedly critical, are never dogmatic or rigid. Solnik’s portrayal of Anna transcends her own personal mythology, preventing the viewers from making too easy an assessment. This is a commendable feat given the melodramatic tropes he has to work with:

A teenager from St. Petersburg moves to Germany with her father’s ballet company, leaves for Berlin in her teens, and is married at 20. She works in a travel agency, one day deciding that there must be more to life. Soon she discovers Berlin’s scarred and sanctified underbelly, a world of parties and constructed glamour ripe for reinvention. She slowly becomes lost in the big city, a Holly Go-Lightly grifter devoid of an authentic self or the comforts of a warm hearth.

Despite scandalizing behavior like spitting on doormen or dancing unabashedly alongside street musicians, Solnik’s depiction never devolves into caricature or gets lost in the Berlin-centric mythos of a party-monster. At home, we see Anna cry about the trials of living in a foreign land and watch “Germany’s Top Model” with rapt attention. But it’s clear that the persona of Anna Pavlova manifests itself best in the public space. At one point Anna asserts that when she takes drugs she’s “in her element.” It’s only when confronted by a more solid sense of place and time that she feels vulnerable.

Film still from "Anna Pavlova" (2011), directed by Theo Solnik. Courtesy the artist.

Solnik asks about her “business” from behind the camera, to which Pavlova coyly responds that she makes “beautiful people’s wishes come true.” The filmmaker occasionally allows us to glimpse beyond the fourth wall as Anna implores and accuses him. On a rainy street in the middle of the night, an aggrieved Anna flatly spits, “you’re a lousy psychiatrist Theo.”

In the film’s most poetic moment, Anna talks to nearby swans dotingly before launching into a diatribe directed at an absentee grandmother in Moscow, trying to prove how “well she is living here.” It’s in this instant, against the idyllic circling swans, that we see the competing sides of Anna Pavlova, who represents at once ecstatic romanticism and its fatalistic surrender.

Addressing Solnik later she says,

“You may film me, but you may not direct me.”

In one of the final scenes, we wince as a hooded male figure tries to take advantage of an intoxicated Anna, tugging at her shirt and trying to coerce her inside a doorway. But there is something redeeming in her response, an expression of physical repulsion and inner strength echoed later when she states,

“I can’t explain why, it’s just me, Anna Pavlova.”