A person’s hair sometimes illustrates the inner workings of the head to which it is attached. Beverly Fishman, my mentor in grad school, has curly hair – not gentle ringlets, but fierce, uncompromising curls. And Beverly Fishman is nothing if not fierce.

A person’s hair sometimes illustrates the inner workings of the head to which it is attached. Beverly Fishman, my mentor in grad school, has curly hair – not gentle ringlets, but fierce, uncompromising curls. And Beverly Fishman is nothing if not fierce.

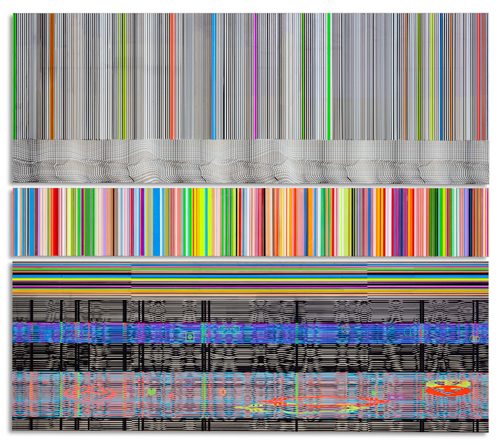

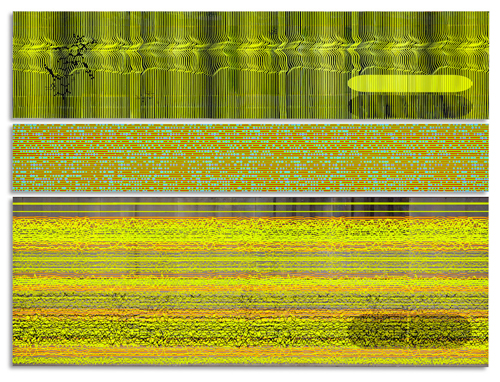

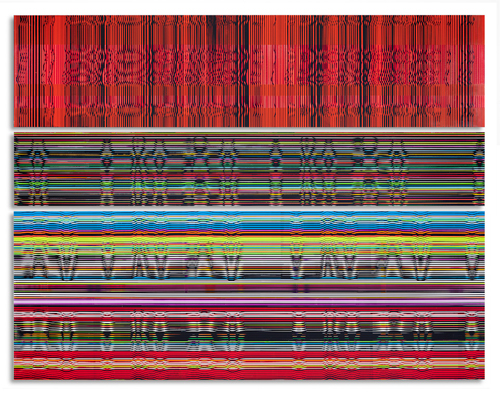

I’ve talked to Bev often since my graduation from Cranbrook a year and a half ago. From the window of Galerie Richard at the opening for her self-titled show last December, I noticed Bev’s hair first; her spiky silhouette was set against the delicate layers of EKG and EEG patterns in her paintings. Inside the gallery, I was surrounded by a swirl of psychedelia; I felt both dazed and dazzled.

Having a great teacher is a mind-altering experience. Great teachers may shock, jolt and intoxicate you. Not unlike the pharmaceutical references in Bev’s work, the effects of a great teacher may last longer than you expect.

A few weeks later I visited the gallery and Bev again. We stood in front of one of her recent works, an array of candy-colored glass capsules called Pill Spill, 2011, as she stated with her encapsulating intensity that two things were certain: she always knew that she wanted to be an artist and she always knew that she wanted to be a teacher.

Nothing would stand between Bev and these goals. Not even a few bad experiences. Not even the type of bad experience that would easily scare other kids away from art.

Bev told me a story. When she was a girl she took an art class. Every week the work of one young artist was highlighted at the end of the class. You might think that an artist as accomplished as Bev has been lauded from infancy. Certainly the works of the young prodigy were acknowledged in her art class.

Bev clarified. Her drawings were never selected at the end of the class; her work was never recognized as extraordinary that year.

There have been trials, there have been errors, but Bev’s force, perhaps like the curls atop her head, is charged from within. Her drive is impervious to the outside world.

For twenty-five years Bev has been teaching and since her memories began recording, she has been an artist. Like Bev and like many of my readers, I can’t be anything but an artist. One day I want to be a teacher, too. To that end, Beverly Fishman agreed to answer a few of my questions about teaching and being an artist.

* * *

Jacquelyn Gleisner: How soon after you graduated with your MFA from Yale in Painting did you begin your teaching career? What was your first teaching experience?

Beverly Fishman: It was a couple of years after the MFA. My first job was teaching contemporary art history at Housatonic Community College in Bridgeport, CT. I got the class ten days before the semester began. I was nervous. I remember giving my first lecture and having more than half the class left over at the end! The class got much better after I quickly figured out how to teach it through museum field trips and artist studio visits. I think the best type of teaching is through dialogue and by everyone in the class bringing their unique perspective to a central topic. I realized early on, that teaching involved trial and error, and that I needed to keep what worked, and throw out the rest. I was working on preparation for that class every day for the entire semester. There is such a huge learning curve in teaching. At that time, I couldn’t have imagined a full-time job with all the added administrative responsibilities that I have now. Being in the studio was a relief!

JG: Before you became the Artist-in-Residence and Head of Painting at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in 1992, you were an Instructor at Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore and you also simultaneously worked as an Associate Professor (adjunct) at the College of New Rochelle, Graduate Art School, in New Rochelle, New York. How did you land these teaching positions?

BF: In each case, I got the job by being recommended by a faculty member who was teaching at the institution. I did not submit a teaching portfolio or a written teaching philosophy. At Maryland, I was first invited to be a final critic in the painting department. I critiqued in front of faculty and many students; you could say it was like an interview. Soon after that I was offered undergraduate paintings classes, something I did for several years. At New Rochelle, I went in for an interview and was offered a class on the spot. I was employed part time in multiple schools for a decade, before getting my first full time teaching job as Artist-in-Residence and Head of Painting at Cranbrook. I would regularly cold-call places where I wanted to teach in order to get work. When you do a lot of part time work, however, you get spread very thin because of commuting times, regular bouts of job applications, and classes canceled because of low enrollments.

JG: While I was a graduate student in your department at Cranbrook, you often talked about time management. You strongly emphasized the importance of knowing how to effectively manage time. You often told us that artists have to compromise constantly and make sacrifices to further and develop a professional practice. As you began your teaching career, how did you learn to manage your time to enable you to make art and teach?

BF: I have always wanted to be an artist and teach. It wasn’t about time management; it was about focusing on what I loved to do. For as long as I’ve been teaching, pretty much my entire social and personal life has centered around art. My friends have always been artists, critics, and curators. (My first mate was an artist, my second a critic, theorist, and historian.) I go to shows and – more recently – I’m constantly looking at art online. For a very long time, I lived very close to the edge. Money was tight. When that is the case, you are always making hard choices, but you do it because you are really into making your art.

My life now allows me to make the work I want to make, and live a very decent life. If you want to make art, then I think you will have to make sacrifices. Chances are that you will not make a lot of money. In addition, you will most probably have to work very hard for a long time before people begin to pay attention. The payoff is that, by being an artist, you get to develop a body of work that is yours: something that is completely personal and simultaneously in dialogue with some of the greatest achievements of human culture. You have to have clear priorities and you have to know how to sustain your work.

JG: The most valuable lesson I learned from you was how to enrich and sustain a personal studio practice as a painter. What are the most essential lessons and experiences that you want to impart to emerging artists?

BF: Your studio should be the center of your life and everything else should circle around that. Invest in your practice by doing material, social, cultural, and art historical research. When you are not making art, then go to shows, museums, read about art, read everything that informs your practice; develop a weird hobby or interest that supports your work. I think it is important to reflect the time that you live in. Make work and develop it though a dialogue with the things in life that are vital to you. Being an artist is a very rich and self-directed life. The rewards are great because you are living out your own vision, but you have to work very hard at it.

JG: I left Cranbrook knowing that there would certainly be difficult times in my career, perhaps especially as a woman. You were supportive, but you never minced your words with me or my fellow graduate students about the complications of a career in the arts. Why have you adopted this frank approach?

BF: When I left graduate school, I was clueless about the life of an artist. We never really spoke about the practical things. If you wanted to teach, then we had guidance on the mechanics of teaching. However, no one really tried to help me understand how to be an artist while working at a job and having a life at the same time. In particular, there was no discussion about how to make one’s way in the art world; that is, target galleries that might want to show you, submit work for consideration, follow up, etc. It was like art stayed in the studio. I know that this is addressed in many schools today, but this was not the case when I was a student.

As an educator, I think it is important to talk to students directly about the difficulties that lie ahead. If you want to be an artist, then you should have a clear idea of what to expect. I try to be supportive yet frank. When teaching undergraduates you can sometimes be more supportive than critical. However, when teaching MFA students, you need to be honest as well as practical. I try to prepare my students for what is to come, so that they can better deal with the curveballs they get thrown, and so that they remain artists, even if they don’t get a gallery show for several years out of school. I am interested in their survival as artists, and also their ability to stick to their guns. To help them, I try to make them aware not just of how to make art, but how to get it out there, and the issues that might arise when they are trying to exhibit. I make a long term mentoring commitment to many of my students, and it’s gratifying to see how many of them remain artists ten and fifteen years after graduation.

JG: Every year you work closely with a small class of emerging artists that you select. You also regularly engage with contemporary artists and other professionals such as critics and writers who are visitors to the department. How have your experiences as a teacher impacted your work as an artist?

BF: I find it invigorating and challenging to work with emerging artists every day. I love their excitement and passion, and they help me to stay open to what’s new in art. That’s one of the fantastic things about teaching at Cranbrook; being an Artist-in-Residence here allows me to engage in sustained dialogue with great young artists and watch them as they develop. This place is a studio based program, which I believe in. My best students surprise me again and again, and help me think about my own work in new ways. In addition, Cranbrook allows me to invite artists whom I respect to give lectures and studio critiques. I take my students to NYC each year, and studio visits are a major part of the trip. You would not believe how generous many contemporary artists are with their time, and how powerful it is to travel to New York or LA and see cutting-edge creators talk about their work and practice in the context of their studio. I want my students to see how things are done at every level of the art world; and to have a conversation with an artist in their work environment often gives you practical knowledge and insight that cannot be gained anywhere else.

JG: Lastly, you’ve been teaching now for twenty-five years. How has your teaching philosophy changed over time?

BF: My core philosophy hasn’t changed that much, but I hope I’ve become a better mentor and educator.

* * *

Beverly Fishman has been the Artist-in-Residence and Head of Painting at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan since 1992.

Pingback: Praxis Makes Perfect | Trial & Error: On Teaching with Beverly Fishman « hellosinki!

Pingback: Praxis Makes Perfect | Trial & Error: On Teaching with Beverly Fishman | Art21 Blog | studiofive10