I first learned of the term horror vacui last semester, when a professor of mine overheard my attempts at describing why I like layering and overprinting in my work. I did some very superficial research and became fascinated with the topic.

I at first wanted this to be a very simple, show-and-tell post: “These are examples of horror vacui,” placed next to images of work by Adolf Wölfli, a carpet page from Kells Illuminated manuscript, or a poster by psychedelic artist Victor Moscoso. But then I became fascinated with all the similarities between these very disparate art movements. Why are people across eras and cultures moved to create work that covers every square inch of their chosen media? What leads them to repetition, ornamentation, or obsession?

To begin, the term horror vacui is often associated with the art critic and scholar Mario Praz (1896-1982). Praz wrote extensively on the history of interior design and decoration and was one of the first critics to comment on these choices as reflections on the individual. He used the term horror vacui in reference to what he saw as the clutter of interior design in the Victorian age.

Aldoph Loos had a similar take in his book Ornament and Crime, believing that evidence of how advanced a culture is can be seen in their use of ornamentation, or lack thereof.

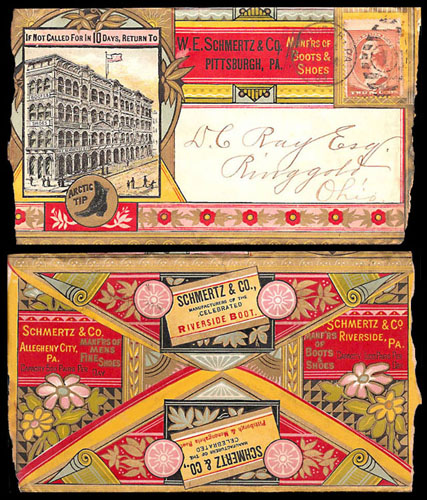

So, it’s easy to assume Loos and Praz would have hated the Artistic Printing movement.

Artistic Printing was a fairly short-lived movement in the 1870s and 80s throughout Western Europe and America. It’s a smorgasborg of fancy typefaces, typographic ornaments, patterns, and colors. Often elements were taken directly from Japanese, Chinese, Moorish, and Egyptians sources for a more “exotic” feel. The Artistic Printing movement grew quickly and with such fervor largely due to an expanding print industry–type foundries were popping up everywhere during this time period. This allowed the foundries and various printing presses to experiment with ornamental rule, color, and images culled from various sources in attempts to attract more business. More subtly, Artistic Printing was influenced as well by a general sense of the power of design and art as championed by the Aesthetic movement.

(It should be noted that the Artistic Printing movement was and is so reviled by art critics and printers alike that it is often not even mentioned in most histories of printmaking. If it is mentioned it is only in the negative: too busy, overdone, tacky, and tasteless.)

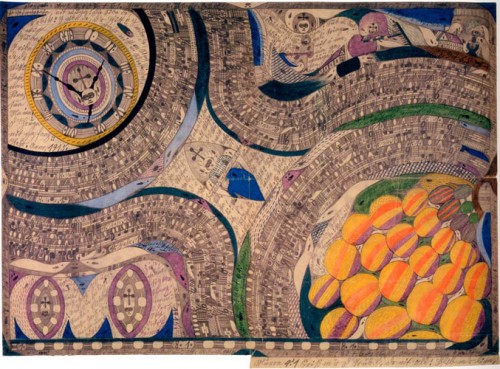

Outsider Art–the art of those who have been diagnosed with mental illness and/or who have not received much if any formal artistic training–is another common example used when referencing horror vacui. Speaking in very broad terms, Outsider Art (which is also referred to as Self-Taught Art, Visionary Art or Intuitive Art) is characterized by the use of heavy symbolism, repetition, and aesthetic choices unconcerned with things like depth or proportion.

The following quotes speak about the art of the mentally ill far more eloquently than I ever could:

“… Because the art of schizophrenics involves unresolved conflicts and ambiguities, it tends to be repetitive, the result of itches that must forever be scratched. Because its basic impulse is not to copy something but in some magical sense forge order, the art tends, in painting and drawing at least, to be flat or otherwise unconcerned with realist visual conventions such as depth and proportion. The symbolic and emotional/physical relationships are much more important. And because for these artists the very act of object-making is itself an episode of integration, the art can often indulge gestures for their own sake, violent or playful games without any communicative purpose. While the artist works, he or she defers chaos and suspends contradictions, and the gestures of art become acts of temporary liberation, even in the midst of anger and fear.”

— Lyle Rexler, How to Look at Outsider Art

“One reason why Outsider Art is characterized by proliferation and abundance is that its metaphoric co-ordinates are so versatile. Whereas the clichés of commonplace thinking are no more than conditioned reflexes set off by standard external prompts, true imaginative thinking is incomparably more inventive and fecund, for it flourishes within an inner space within which reigns an infinite zest for cross-references, or what the poet Charles Baudelaire calls correspondences. In the formation of the artwork, metaphoric resonance offers the widest latitude for symbolic or allegorical signification. What might be termed panoptic imagining is the key to original work in all poetry and visual arts. The Surrealists were on the right track when they sought to codify the procedures through which one might gain access to this key; their theory of automatism (expression emanating from spontaneous non-rationalized gesturing) rests upon a demonstration of the metamorphic versatility of pictorial or verbal expression, once it is released from the mundane chores of describing external situations or articulating a consensus. Whatever forms of repression continue to exist in our world (and there are many), freedom of expression must still be counted sine qua non of authenticity and dignity, most particularly within the very special context of art making.”

— Roger Cardinal, “Worlds Within,” Inner Worlds Outside

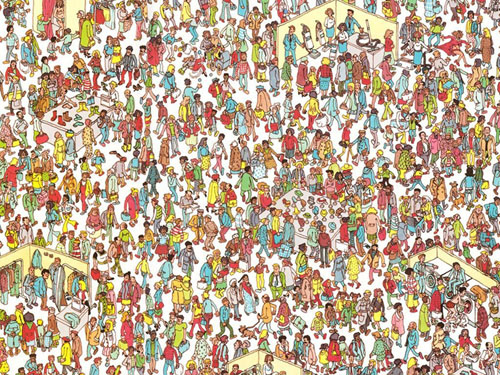

In the interest of brevity I’ll stop here but I encourage readers to also consider the psychedelic poster art of the 1960s, the art of Jean Duvet, yarn paintings of the Huichol people, or even a Where’s Waldo? book, when contemplating the topic of horror vacui.

What many critics may call naiveté in these works I see as the courage to reach into unknown spaces. Though hailing from different countries and time periods, many artists working in these styles–covering their entire chosen media, wild encompassing of disparate source topics, etc–are creating new narratives that previously did not exist. They are reaching out to create new worlds, ordered as how they would see the one we currently exist in.

And while it may seem very easy to write off many of these styles as too alien, too other, too unlike yourself — made by artists who are institutionalized, uneducated, from other cultures, etc–think again, as you reach for your Iphone/Ipad/laptop/whatever to surf/text/play Scrabble in order to fill your “empty” time.

Special thanks to my professor Patty Smith for first introducing me to the term horror vacui and to UArts reference librarian Sara J. MacDonald for all her research aid.