A specialist sorts through books damaged in the fire at the Institut d'Egypte. Image from mauriceincairo.blogspot.com.

Researchers who work in the ambiguously defined “Middle East/North Africa” region inevitably complain about the intimidating, confusing bureaucracy that interrupts their access to primary sources. In Egypt, for instance, the state maintains strict control over the national archives and libraries, restricting which researchers have access to what documents. And many primary sources relating to the arts are not archived or catalogued in these institutions at all, meaning a whole different type of limitation is at work – restriction by omission.

In my own research on mid-century Egyptian art history, I often proceed by seeking out information in the form of oral histories, or by consulting pertinent documents in private collections. For instance, I frequent the home of an elderly woman who is the widow of one of Egypt’s best known modernist painters, spending many afternoons sifting through stacks of old notebooks, letters and family photos. But even her personal, family archives suffer from gaps and omissions—the result of various curators and Ministry of Culture officials who have helped themselves to her collection over the years. And while I’ve found that the state-operated Museum of Modern Egyptian Art has become increasingly transparent over the past year (thanks to the efforts of its newly appointed director), new obstacles arose for my research when I realized how many items were inexplicably missing from the institution’s storage rooms.

My sometimes exciting, sometimes amusing, sometimes frustrating attempts to obtain a particular form of knowledge have been like a micro-scale, domesticated version of much broader, much more difficult attempts to access information about current political realities. Life and work in Cairo has often felt absurd in the past months, due to how little I am actually able to understand the events that surround me. With each new episode of violence, I read both independent and state news sources to compare their coverage, while relying heavily on less mediated media for information, like Twitter, blogs, and YouTube videos, or on stories from friends who had been present at the latest clashes. But none of these testimonies cohere into one cogent narrative—it’s difficult to understand exactly what happened, and essentially impossible to understand why, as the military government, the protesters, and other parties contest the authorship of this rapidly unfolding history.

The writing of the so-called “revolution” isn’t just a question of the authorship of future events, but also of the re-writing of Egypt’s past. Since last January the uprisings have been punctuated with dramatic cases of the destruction of archives and historical material, from the burning of state documents in the Interior Ministry on January 28, 2011, to the alleged ongoing destruction of documents by government officials to, more recently, the highly mediatized burning of the Institut d’Egypte, the neglected depository for hundreds of thousands of books and documents. It’s often unclear as to who is behind the destruction, with protesters and state officials pointing the finger at each other as the cause for these ever-widening holes in the historical record.

As a researcher in the midst of these crumbling, contested, partially written and yet-to-be-written histories, the tenuous instability of the notion of social (art) history and archival research has been dramatically foregrounded. Of course, as I discussed in my last column, working on something like art history can feel disturbingly self-indulgent in these times of crisis; but at the same time, the process of attempting to recover, record and preserve lost (or suppressed) historical narratives feels very intimately connected to this moment.

Of course, even before the Arab Spring, there was a particular, political urgency to the notion of archival research and historical preservation within regional cultural production. For a little over a decade, various artist projects and organizational initiatives have made up for the lack of traditional research materials by mining typically overlooked artifacts from popular visual culture, oral histories, and the like. In 2010, the Townhouse hosted the “Speak, Memory” symposium to reflect on these various strategies and tactics. An intensive, 4-day event, “Speak, Memory” brought together artists, researchers and writers from the region and other places in the so-called “periphery,” where cultural workers struggle with issues of access to materials; contest hegemonic historical narratives; and find ways to give voice to repressed histories.

Within the region, one of the best known examples is, of course, Walid Ra’ad and the Atlas Group. Ra’ad has used the notion of the archive as an organizational device since the late 1990s, in large part to explore the impossibility of writing history (or understanding the present) in post-civil war Lebanon. As part of this same impulse, the Arab Image Foundation was founded in Beirut in 1997. This non-profit organization dedicated to amassing an archive of photographs from the region and the Arab diaspora has engendered dozens of projects that have attempted to render visible forgotten, abandoned images and stories that were otherwise unaccounted for.

These Beiruit-based initiatives were the pioneers in archival activity, but by the mid-2000s, an ever-increasing number of archival initiatives were developed pan-regionally. In 2008, Beirut-based artists and researchers Kristine Khouri and Rasha Salti started the “History of Arab Modernities in the Visual Arts Study Group” as an answer to the paucity of primary sources in art histories from the Arab world (whether because such sources have been destroyed or simply remain inaccessible), as well as developing platforms and networks to share those sources and related research.

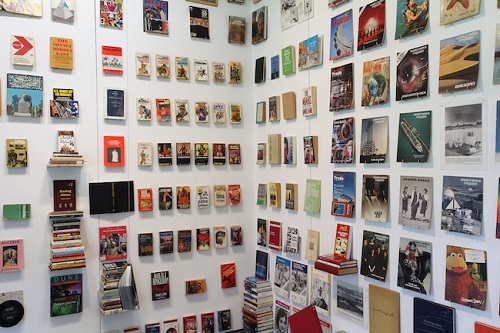

Shortly thereafter, in 2009, the New York-based cultural quarterly Bidoun launched the Bidoun Library, a traveling collection of printed matter pertaining to the region (including objects ranging from pulp fiction novels about harems to beautiful art books crafted by Slavs and Tatars) that intends to lay bare the complex portraits of the Arab world that have been developed both in and outside of the region. That year Bidoun also partnered with the fantastic online archive of experimental film and sound, UbuWeb, to create a special curated selection of rare new media work from the MENA region – BubuWeb.

Some of these projects, as well as several others, were presented and discussed at the “Speak, Memory” symposium at the end of 2010, when none of the participants could have predicted how radically their priorities were about to shift. By the time the symposium proceedings were published in a catalogue a few months later, Egypt was suddenly a very different place. The demonstrations that would ultimately topple the Mubarak regime had already swept through downtown Cairo by the time the catalogue appeared, and these questions of access and preservation took on a very different dimension.

Mai El Wakil, the cultural editor for the online daily Egypt Independent, was commissioned to write an epilogue for the “Speak, Memory” publication, titled “Can a History of the Egyptian Revolution be Written?” In her essay, she eloquently brings those discussions from 2010 into the current context, describing the ways that several of the issues that the artists and cultural workers brought up during the symposium (such as the blurry boundaries between “history” and “memory,” and whether or not that distinction needs to be preserved) have now been transferred into this social-political realm. Indeed, archive fever gripped the nation after last January, with a multitude of initiatives dedicated to documenting and preserving the memory of the political events in ways that counter the state stranglehold on media and history-making (such as the activist and artist-led, archival documentary organization Mosireen; or the online video archive 18daysinegypt.com).

These new archival initiatives will certainly have continued political solvency not only for the ways in which the fill in infrastructural gaps in the recording and preservation of history-making moments and records; but also for their potential to impact the crafting of future narratives around this moment. And they also bear reminder to the important responsibilities regarding the ways in which culture from this moment is documented, written about, and remembered. The different strategies for recovering repressed cultural memories that were discussed in downtown Cairo in 2010 remain essential not only for re-visiting the region’s history, but for narrating its present and future, in all of its complexities and ambivalence.