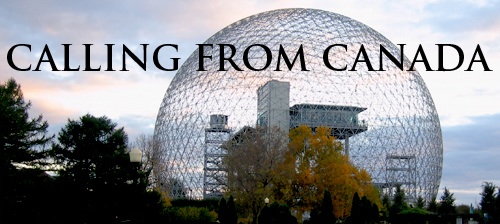

At the Vancouver Art Gallery’s exhibition Shore, Forest and Beyond: Art from the Audain Collection, I saw a middle-aged man facing an Emily Carr painting. He let out a slow whistle in disbelief, and turned to his friend to ask incredulously: “How have I never seen this before?” I understood his sense of discovery. The early Emily Carr work depicted an Arbutus – the common west coast tree characterized by its orange-red flaking bark. The colouration in the painting is expressive rather than realistic, making it quite different from the oeuvre of dark and deep forests more commonly associated with the artist’s work (as exemplified in the image below).

Emily Carr. "Quiet," 1942. Oil on canvas. Collection of Michael Audain and Yoshiko Karasawa. Photo Heffel Fine Art Auction.

The painting was a kind of revelation; insight into Carr’s vision that appears, luckily, as part of an important exhibition that closed last month at the VAG – 170 works from the private collection of philanthropist Michael Audain and his wife Yoshiko Karasawa. Given that Audain’s holdings are considered one of the most significant private collections in all of Canada, the show was surprisingly personal and emotional.

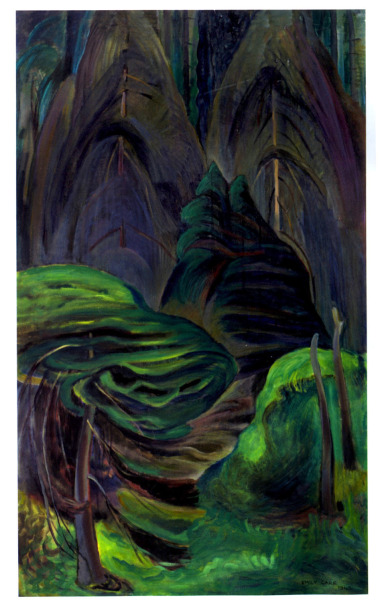

Predominantly focused on works of art from British Columbia, the exhibit included significant 19th-century First Nations masks, stunning Emily Carr paintings, and an array of contemporary Vancouver artists including Jeff Wall, Stan Douglas and Ken Lum. Audain’s support for British Columbia artists has been massive, as has his support of Mexican modernist painters. One room at the VAG contained art by Jose Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siquieros, and the only self-portrait by Diego Rivera still belonging to a private collector.

Diego Rivera. "Autorretrato (The Firestone Self-Portrait)," 1941. Collection of Michael Audain and Yoshiko Karasawa. Courtesy of Vancouver Art Gallery.

Despite the staggering star power of the collection, walking among these works felt like walking through someone’s living room: intimate. Each art work was personified by its connection to the remarkable man who had selected it. In front of a huge and daunting, hairy Kwakwaka’wakw mask by Beau Dick, and a Tlingit owl mask from the 1840s, I wondered what led Audain to purchase these works, which currently hang in his den. What do they say to him?

Tlingit Artist Owl Mask, 1840s-60s. Collection of Michael Audain and Yoshiko Karasawa. Courtesy of Vancouver Art Gallery.

Having never been a huge fan of E.J. Hughes, in the context of the collection I suddenly found myself appreciating what his painting Departure from Nanaimo would have represented to a man who returned to Victoria B.C. via ferry in 1946. It currently hangs in the owner’s bedroom. Model Pole by Jim Hart is the most exquisite example I witnessed of Haida carving. A 16-foot painting by Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun called Burying Another Face of Racism on First Nations Soil makes a strong political statement that most collectors would shy from. Even the Emily Carr watercolors in the collection are atypical. They span different stages in the artist’s career, and exhibit different styles. Remarkably, it’s as though the array of art works are in dialogue with one another, speaking across the halls and rooms of the gallery, perhaps in the way that they might do so with Audain and his wife in their home where the works normally hang.

E.J. Hughes. "Departure from Nanaimo," 1964. Collection of Michael Audain and Yoshiko Karasawa. Courtesy of Vancouver Art Gallery.

For Audain, collecting has never been a posturing gesture through which to flaunt his wealth. In a compelling video interview on view in the exhibition, Audain unabashedly reveals that he has never taken an art history course. Audain says he bought his first work of art for “fifty-dollars including framing” while he and his wife made do with secondhand mattresses from Salvation Army for furnishings. He said that both then and now, he purchases works on an emotional level, and with a vision to repatriate art from British Columbia. Audain told the CBC: “I actually have conversations with the masks that inhabit my den at home. What I tell them is that you traveled long and far and you’ve gone through many hands but you are now almost home, back on the coast. I have made a pledge to my masks that they will never be sold again.” Seen from this angle, this is art philanthropy at its ideal, with social action and responsibility at its core. Audain himself is no stranger to activism. In 1961, before he became the wealthy CEO of a home development company, he was arrested as one of the few Canadians to join the Freedom Riders who, despite threats and violence, fought against racial segregation in the American South.

Despite profiting from big business himself, Audain has been open with the media about the need for increased support for the arts from the Canadian government (which is currently Conservative and continuously draininh resources to the arts). And yet, for all the do-gooding I’ve listed, of course there are also obvious pitfalls to private collections.

Exclusive ownership of artworks often results in them being withheld from public view. I’ve seen such collections, stored in temperature-monitored warehouses; the works are like a sad secret hidden from view, hardly appreciated other than for the “aura” of their existence. Audain, on the other hand, has vowed to never put his paintings away in vaults as some kind of imprisoned investment. They can instead be seen hanging on walls throughout his home (and some in his office), and only for a few months were they displayed at VAG with a desire to eventually donate them to institutions. Keeping works locked away in one’s home could be seen to have similar ramifications as putting them in storage. Audain has never opened his home to tours of his collection and obviously, he need not be obliged to. And yet, upon beholding a precious Diego Riviera self-portrait or a stunning Emily Carr (which, by the way, I would not have seen if it were not for this exhibition), my breath was literally taken away. At some point, should all historical or otherwise significant works of art be made publicly viewable? Audain finally became convinced to share his private collection through the VAG when curator Ian Thom suggested that it could be construed as “selfish” to not share these works with countless curious minds eager to encounter the morsels of history and culture they impart. Of course, while many collectors do loan their works to museums, still many do not. Masterworks exist in private holdings that may get passed on as heirlooms, with nary a chance to be seen by new eyes. Should museum curators urge private collectors to display their collections at major museums? Are public museums–rather than private collections–the safest place to build collections?

I visited the exhibition a few times before it closed. On its final day, I overheard a staff person speaking to another about how sad they were to see it go. They were sincere in their emotion. This hodgepodge of stunning treasures was returning home to its owners, literally, and it would likely be a long time before it would be let out to play again.