My friend Lauren invited me to the lecture, but she couldn’t remember the name of the artist or anything about his work. I wasn’t doing anything Friday night, so I said yes, and that’s how we ended up in the theater of California College of the Arts while photographer Jason Fulford spoke on stage. He sat behind a desk decorated with an onyx vase filled with crepe paper ranunculus found at a thrift store, a ceramic turtle with a rubber ball balanced on its shell, a framed image of Lucian Freud taken from a book, and a placard with the words “Desk Sign” written on it.

Fulford is a cultivator of serendipity. In his March 2, 2012, lecture, he traced the circuitous route this force has carved through his life and his work. He described the motorcycle ride he took across the country after art school; he told of visiting the spot in Minnesota where the waters of the Mississippi River first begin to flow. He talked about stopping for a meal in Scranton, Pennsylvania, and returning to live there two years later for no real reason, just because. As he recounted the random steps he’s taken over the past twenty years, the resulting road seemed inevitable, as though he had created and followed it at the same time.

Flea Market, Scranton, Pennsylvania, Jason Fulford. Photo courtesy the artist.

Flea Market, Scranton, Pennsylvania, Jason Fulford. Photo courtesy the artist.

Flea Market, Scranton, Pennsylvania, Jason Fulford. Photo courtesy the artist.

The same principles guide his photography. Fulford lets his eyes wander and, with his square-format Hasseblad camera, records the places they rest. He photographs strange shadows, rhyming shapes, visual absurdities, and simple forms. After a period of time, a month or several, he arranges his recent pictures into a contact sheet and compares. It’s then he notices relationships, draws out repetitions, and rearranges accordingly. Though the finished layout appears premeditated, he arrives at it through chance and convergence.

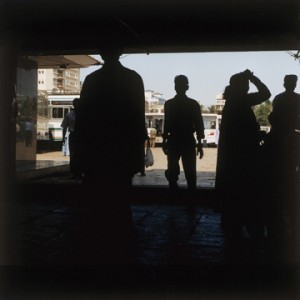

"Mumbai," 2000. Jason Fulford. From the book Crushed. Photo courtesy the artist.

Photo sequence, Jason Fulford. Photo courtesy the artist.

His method reminds me of the way I shop at thrift stores. I move from rack to rack, guided by the sight of a pleasing tweed or an intriguing floral, attracted to thick wools and antiquated patterns. I choose garments based on price and desire. It’s only in the dressing room that I notice latent themes: an abundance of paisley, five pencil skirts, three button-down shirts, all with bows at their collars. Clues to my subconscious emerge, and unintentional costumes form.

Fulford’s editing process mimics the progression of a syllogism, in which a logical conclusion is drawn from two premises (he gave the example of a=b, and b=c, so a=c). He starts with one image (a) and finds its complement (b), and then finds its complement (c). He then takes away the middle image (b), and we are left pondering the connection between a and c, imagining the contours of what’s been removed. Through this practice of omission, Fulford generates new meanings. As in an elliptical narrative or mystery, the missing pieces become the most important thing.

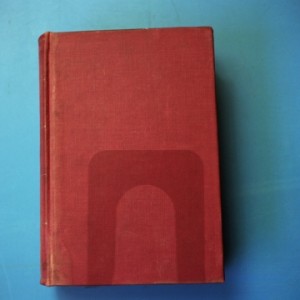

I thought of a photograph Fulford showed Friday night in which an opaque shadow functions as the central figure. I thought of his picture of a book imprinted with the outline of a bookend removed after years of support. In both, the negative space is the focal point.

Silhouettes, Jason Fulford. Photo courtesy the artist.

A book at the Prelinger Library, San Francisco, Jason Fulford. Photographed for Harper's magazine. Photo courtesy the artist.

These equations, in which we are given two pieces of information and must deduce their relationship, happen all the time. A few weeks ago I bought two pairs of pants at the Salvation Army. They were the same style, the same brand, and the same size. One was navy blue, the other black. In the dressing room I saw someone had written “BLUE” on the label of the former. Suddenly the two objects suggested a third: I imagined an elderly woman who once owned both pairs. She mistakenly wore her blue pants when she meant to wear her black. She put a note on the label to make up for her failing eyes, then finally gave up and donated both pairs to the thrift store.

Two pants, black and blue. Blue ones on the right. Photo courtesy the author.

Scranton, 2009. Jason Fulford. From the book The Mushroom Collector, by Jason Fulford.

Coincidences rely on missing information; we must suspect connections but be unable to prove them. These gaps in logic can be fertile grounds in which we are encouraged to conjure uncanny possibilities. One day a sign appeared in my neighborhood describing a lost Egyptian goose that a psychic had intuited was nearby.

I stopped while walking home to read it, and the next day a dead Canada goose floated in the small estuary beneath it. Were the two events related? Was there a goosenapper on the loose? A practical joker? A psychic with a mean streak? I’ll never know, and I prefer it this way. Fulford directs us to such suggestions of synchronicity, and it is through their corresponding shortages of explanation that life is able to startle us anew.

Pingback: Oct 30 – Jason Fulford | CCC Photography Graduate Forum