It’s unclear exactly where the next two weeks of guest blogging is going to go. Most likely, it will go where I do, weaving alongside my own paths through the near future. I’m always in the middle of things, the swamp of possibilities mucks wide in all directions, and most of my own work grows out of the murky waters of humdrum everyday existence. The day-to-day is inspiring and endlessly exciting, and if it’s not, I’ll pretend (at least for the next couple of weeks) that it is. I’m going to treat this blog as a scrapbook of sorts, a cataloging of what’s up, what’s new, what’s going on. It sounds boring when I say it like that, and maybe it will be, or maybe boring’s just in the eye of the beholder.

Yesterday, while visiting Chicago, I went to the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (MCA) with my grandmother. She’s 96 and awesome, but I was a bit shocked by a comment she made about one particular photograph showing an object sitting on a counter. I don’t want to go into the particulars, as they aren’t important really, but her comment stuck with me: “How can that be in a museum? It’s so…. ordinary.” Her other comments about my messy hair and the fact that my orange hat didn’t match my red jacket didn’t bother me quite so much, but the comment about the ordinary struck a nerve. I find nothing ordinary about the ordinary.

The particulars are where the poetry lies; the devil is in the details. A closer look reveals meaning. Clues to narrative are everywhere, and everyone loves a good tale. Joan Didion brilliantly begins her essay “The White Album” by writing, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.”

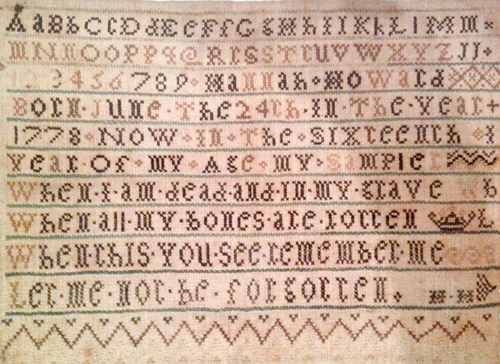

To live and to be immortal. This sampler by Hannah Howard, made in 1793/94 says, “When I am dead and in my grave, when all my bones are rotten; when this you see, remember me. Let me not be forgotten.”

Hannah Howard was sixteen when she made this sampler. According to the wall text at the Art Institute of Chicago, where I saw it in the current exhibition Fabric of a New Nation: American Needlework and Textiles, 1776-1840, Howard was the great great grandmother of Ruth Burns Lord, who was married to A. Russell Lord. In 1968, Mr. Lord donated the sampler to the Art Institute in memory of his wife, thusly ensuring that neither Hannah nor Ruth shall be forgotten.

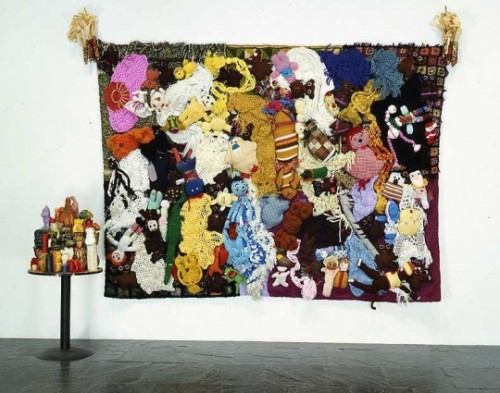

At the MCA, Mike Kelley’s More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid and the Wages of Sin is part of the exhibition about art in the 1980’s titled This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980’s. I didn’t expect to see Kelley’s piece there. I rounded the corner and found myself face to face with a work that surprised me long ago in a very different way than it does now. When I first saw it, I found it gross and perplexing. All that dirty acrylic! All that ugly! The work was challenging, weird, icky, unnerving, abject, with a title dripping with guilt, obligation, and the the impossible economics of affection. It was nasty, sentimental, fucked up, and wrong, and as an undergraduate art student at the time, I was just starting to understand that these were the characteristics that could make work memorable, exciting, compelling and relevant.

Mike Kelley. “More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid” and “The Wages of Sin,” 1987, installation view at Whitney Museum of American Art. Stuffed fabric toys and afghans on canvas with dried corn, wax candles on wood and metal base; 90 x 119 1/4 x 5 inches. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Purchase, with funds from the Painting and Sculpture Committee 89.13a-e Photo by Sandak/Macmillan Publishing Company, photograph copyright © Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Two decades later, the piece is beautiful, sad, and powerful. Instead of feeling like I might get scabies just by looking at it, I’m struck by its formal perfection. The composition of blankets and animals are carefully sewn into a flawless rectangle. Folds in the blankets are carefully preserved in this vertical display, and stuffed animals are all placed precisely. Next to the collage of handmade acrylic is the construction of drippy wax candles, shaped like mushrooms and pillars. It’s hard not to imagine them lit, to try to understand what that blaze of glory might look like. The immortality of the museum ensures that these candles will never host fire, but will retain their clean messiness for future generations to ponder. Already, in the twenty-five years since the piece was made, so much has changed. The stuffed toys, candles and afghans, recent acquisitions from the thrift store when the piece was made, now appear as a time capsule of another era. And of course, the obvious. When did the museum change the wall labels to reflect that the artist died just a few months ago? At the Art Institute, too, the labels had been updated. Whose somber responsibility is it to comb the obits and update wall labels for accuracy? And who gets the job of replacing the label with the new one before a visitor does the job with a sharpie and gets thrown out of the galleries?

No photography is allowed in the MCA’s exhibition, but “More Love Hours…” got its own special sign warning visitors not to take a picture. While I was there, three visitors were chastised by security for trying. The room was mobbed. It was family day at the museum.

After the MCA, I stopped at Chicago Zinefest at Columbia College, which was full of scruffy self-publishers selling their wares. Most contemporary zines have a sweetness to them. Illustrations of kittens abound. I love kittens, but I was on the lookout for zines that were gross and wrong. My favorite zine of all time is called “Whore” and as far as I know there was only one issue of it printed, and it features a really bad drawing of McCauley Culkin on the cover and looks like it was put together on a 24 hour bender by some pissed-off stoner somewhere. I don’t know where it’s from or where I got it, but that zine occupies a special place in my heart, and I’m always keeping an eye out for something in that genre.

I picked up a copy of Black Metal of the Americas Vol. 1 from a sullen guy manning a sparse table, a publication which seems to be a response to Liturgy’s black metal essay and consists of reviews of and interviews with bands that don’t have manifestos. Marc Fischer’s booth as Temporary Services/Half Letter Press was of course awesome. Marc and I went on a quick tour of the zine stands just before Zinefest closed for the evening and found this very sweet lady making Shitty Guru and Purgative Pamphlet. Heartwarming.