Last Thursday was International Women’s Day (IWD)—a day that has taken on a somewhat haunted dimension in Egypt. A year ago, a women’s march in celebration of IWD was violently dispersed when the marchers were taunted and attacked; on that same day, other women protesting in the square were arrested, and several subjected to forced virginity tests. This year, marches commemorating that trauma took place with a spirit of peacefulness, as an activist youth group, NooNeswa, took to the streets of Cairo to optimistically spray paint stenciled portraits of famous women from the region as part of the Grafitti Harimi project (an attempt to reinsert the women in public space in a positive – if youthfully naïve – light). But that optimism took a blow when, only a few days later, the news broke that the military doctor charged with performing those highly mediatized virginity tests has been acquitted.

These events over the past few days have reminded me of how difficult it is to write about gender in Egypt, even when it’s so prominently thrust to the forefront of everyday discussions. It’s a difficulty that is perhaps particular to my situation. As a rule, I avoid addressing issues of gender when I write about arts in the region. It’s an endeavor that would be doomed to fail, given my perspective as a foreigner (with all of the imperialist connotations that status entails), as well as the fact that the history and cultural understandings of feminism are deeply specific to the region — a real departure from the canonical reading lists in the subject that I’m familiar with.

These basic problems in terms of lack of expertise or credibility are compounded by the fact that art about women has long been a favorite commodity for curatorial tourists capitalizing on the post-9/11 market for all things Middle East—especially if a woman in a veil is involved (Shadi Ghadirian’s cringeworthy, essentialized photographs are an obvious example). The easiest way to steer clear of the ideologically fraught quagmire of writing about art and gender in this context is to dodge the issue altogether.

And it’s not difficult to do so. Many artists in Egypt are even more eager to avoid being labeled with obvious geopolitical categories, and the related essentialist stereotypes, than I am to inadvertently dole them out. Artists have largely retained a commitment to the integrity of their work, successfully resisting the desires of the market to push or pull them in gendered directions. And those artists that have taken on gender issues have done so in far more nuanced, challenging ways than taking a photo of a veiled woman with a teacup for a face.

For instance, artist and cultural historian Huda Lutfi has explored the relationship of specifically gendered iconography to the iconography of nationalism, mythology, and historical memory in collage and sculptural installations for several years. Another excellent example is performance artist Amal Kenawy, who has presented highly charged performances that involve (amongst other things) notions of gendered labor—like “The Room,” a video piece and live performance first presented at Townhouse in 2002. The work saw Kenawy embroidering an animal’s heart as a video played showing a bride with white lace gloves engaged in the same endeavor. In a 2007 performance at Darat al Funun in Jordan, she used the same video as the backdrop to a live performance where she painstakingly sewed, and then burned, a wedding dress. Also in 2007, Kenawy wrapped an abandoned building in Sharjah in cuddly, pink quilted material that she tenderly stitched together in an almost maternal gesture.

But, along with everything else, ways of representing, questioning or challenging gender in the visual arts have changed over the past year in Egypt. The notion of “woman” as a category has become mediatized to an unprecedented degree — if forms of cultural expression have been a recurring trope in Western media coverage of the uprisings in Egypt, that attention comes a distant second to the amount of coverage devoted to the representation of women. The role of women demonstrators, nurses and doctors in Tahrir; sexual harassment in the square and elsewhere; the case of the virginity tests – these have been recurring lead stories for the past year.

Historically in Egypt, waves of feminist movements have crescendoed during key moments of the development of the nationalist project, and the current moment continues in this trend. The difference now, of course, is the visuality of the whole project. Most of the news stories mentioned above center on photographic images, which have also become rallying points for continued demonstrations against the brutality of the military government. These range from utopian photographs of women protestors protected by a human chain in Tahrir, to sickening images of violence targeted specifically against women protestors – most iconically, the photograph of “Tahrir girl,” which showed soldiers stripping a woman of her headscarf and abeya and preparing to kick her in the stomach. That photograph in particular almost instantaneously spawned a whole series of related imagery as soon as it was tweeted.

There’s also been an emerging (or perhaps re-emerging) genre of feminist activism via self-representation. Most famously, of course, there’s 20-year old Egyptian art student Aliaa Magda Elmahdy’s nude, provocatively posed photograph of herself, which she posted to her blog and sent out to the world over twitter last November. The photo garnered Aliaa a fair amount of approbation, threats, and legal worries, but also won her widespread fame. The photograph itself has endlessly re-circulated through different media, constantly being re-appropriated to different ends – even turned into a stencil and spray painted in the streets of Cairo.

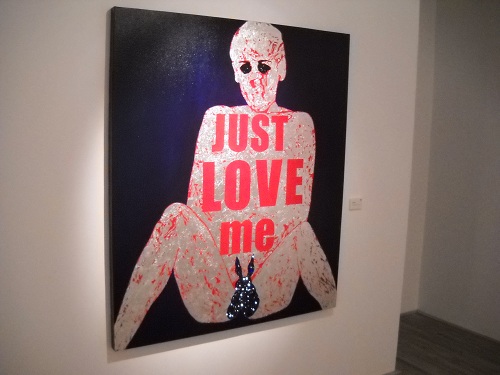

This inescapable flood of imagery and discourse from both within and without the region has inevitably been represented on gallery walls. In fact, the day before Women’s Day, an exhibition of paintings by Egyptian artist Nadine Hammam, “Tank Girl,” opened at Gallery Misr, a gleaming new white cube space in the trendy, upscale Zamalek neighborhood. The show proposed a series of paintings of provocatively posed nude female forms with a little revolutionary-chic imagery thrown in for maximum salability.

Nadine Hammam has been something of a succès-de-scandale in Cairo and the broader region for her paintings of nudes, and their allusions to relatively taboo social issues like prostitution and stereotypically male sexual fantasies. In 2008, Hammam’s first solo show at the Townhouse, “Akl Aish” (a colloquial expression that translates as “making a living”) was a series of paintings showing typical categories of “professional” women (prostitute, housewife, domestic employee, businesswoman) posing nude. The forms are highly abstracted, presented as flat, linear blocks of color; a thick, pastel-colored censor’s bar cuts across their faces, definitively ensuring their anonymity.

This early series touched on fairly interesting issues: the stripping of identity that results in the objectification/commodification of the female form; the problems of representation of women in general in a dominantly conservative environment; and women’s relative agency (or lack thereof) over the flow of capital. Neither the concept nor the execution was exactly ground-breaking, but it was relatively novel in Cairo at the time.

The artist is hardly unique in representing nudes in her work—Egyptian artists from George Baghory to Weaam al-Masry have painted nude women and found an eager market for them without too much trouble. But Hammam has, on the whole, enjoyed a tremendously positive critical reception that has mainly focused on her bravery for showing such sensitive material in such a conservative city. Her reception abroad as also been positive– after all, there’s nothing Western curators love more than a woman artist from the Middle East who deals with the representation of women (look no further than Shirin Neshat). Interest in Hammam’s work only increased after the Revolution; at Art Dubai in 2011, her painting “Got Love” sold for five figures.

And as I argued more extensively here in my review of “Tank Girl,” it’s that commercial success that casts Hammam’s work in a different light in 2012. In a moment when the issue of the depiction of the female body has perhaps never been more pressing in Egypt, what does it mean to show these slick, sparkly paintings of nude women putting themselves on display for the male consumer? Especially when one of those women is shown astride a domesticated, bright pink tank that ejaculates a stream of plastic rats in between her legs? Given that the show almost sold out on the opening night, Hammam clearly hit the iconography jackpot – sexy girls (that still aren’t too provocative) plus some girl-power revolutionary references. It’s a superbly salable combination that plays a little too easily on a somewhat morbid appetite for violent and sexualized imagery, but imagery that’s been tamed down enough to hang up in your living room.

In the same way that the idea of the revolution was commoditized even as it was happening in Egypt (corporations from Coke to Mobinil produced revolution-centric ads almost immediately after the ouster of Mubarak), “Tank Girl” seems a little too quick to capitalize on current events. On the one hand, some young artists have eagerly called for provocation, any provocation, in the art scene just to give the community a good, healthy shake now that the public sphere is opening up in unprecedented ways. But Hammam’s work isn’t provocative or critical enough to meaningfully contribute to any conversation regarding the feminist activism that she vaguely alludes to in her work.

Feminist organizations and activists in Egypt fear that, after coming so dramatically to the forefront of discourse, the issue of women’s rights will soon be obscured by what some consider to be more immediately pressing issues, like the presidential elections and the economy. The ideological tenor of the newly elected government will also be a deciding factor in how open public discourse will continue to be regarding women’s rights.

However, others remain hopeful that perhaps the floodgates have been opened, in a way, and these issues will continue to percolate in civil society. I do anticipate that, at least, these issues will continue to surface in the work of local artists; but hopefully, with the passing of time, they will be manifest in more measured and critical ways.