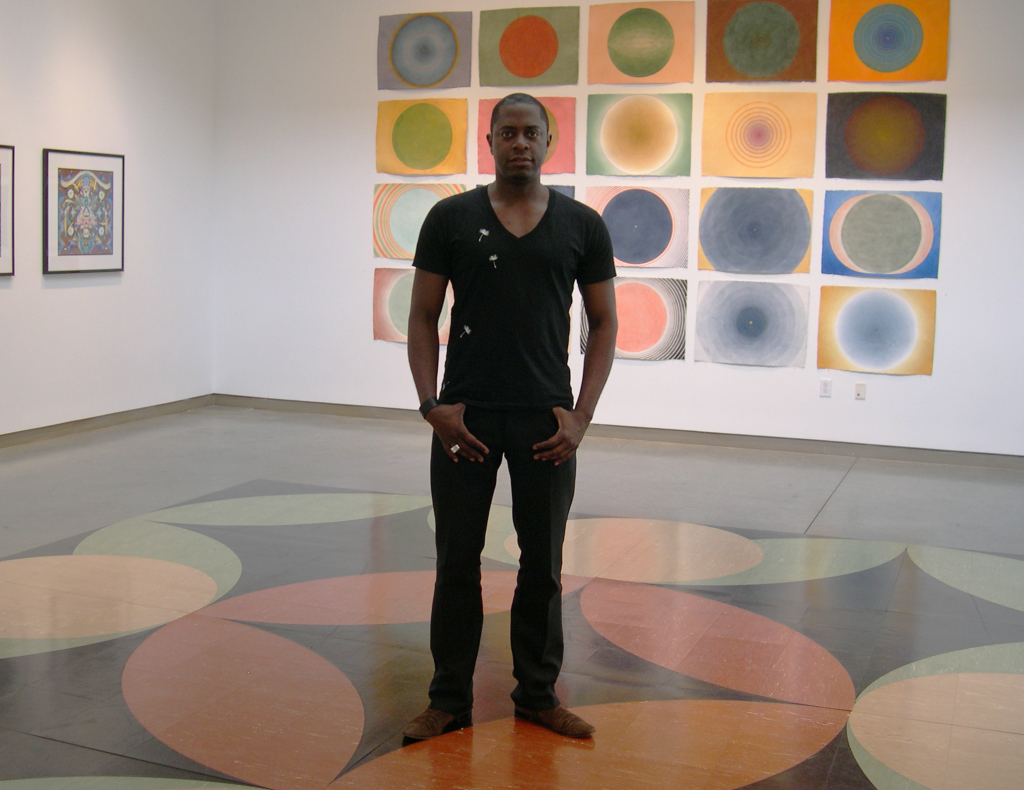

Sanford Biggers and the contemporary Mandala (2012). Emory Visual Arts Gallery. Photo by the author.

As part of Contemporary Mandala: New Audiences, New Forms, Emory University’s Visual Arts Gallery (Atlanta) is hosting a series of interesting events and exhibitions, including (with Art Papers Live!) An Evening with Sanford Biggers on March 21 and an Artist Peer Learning Session on March 22. The exhibit merges contemporary art and the mandala as a form of artistic expression and a tool for transformation and balance. The exhibit is curated by Visual Arts chair Julia Kjelgaard in conversation with author Jacquelynn Baas to dialogue with the Michael C. Carlos Museum’s Mandala: Sacred Circle in Tibetan Buddhism. Mandala of the B-Bodhisattva II by artist Sanford Biggers and David Ellis forms the centerpiece of the gallery, providing a dynamic space for performance.

Artist and gallery director Lisa Alembik notes that the traditional Mandala, a two-dimensional circular painting drawn with colored sand, represents a temple blueprint for a Buddhist or Hindu deity who resides at the center of the structure. This work is used as an aid in meditation, acting as a guide in one’s search for enlightenment. My first experience watching the creation of a Mandala was with the Venerable Tenzin Yignyen at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design (Boston). This included daily meditations and a dismantling ceremony, where the sand Mandala was swept away and the sand poured into the Fens nearby. The lesson I learned from Tenzin was the realization of impermanence of life. With Biggers’ floor piece I pondered the contingency and ephemerality of performance. Prior to Biggers’ talk we convened in the gallery to watch breakdancing and step performances by Emory students. The dance floor was also used for Emory professor Anna Leo’s modern dance class.

Sanford Biggers. "Mandala of the B-Bodhisattva II,"2012. Emory Visual Arts Gallery. Photo by Faith McClure.

Alembik writes that the Mandala “is not fixed or limited in either form or concept.” Biggers references the Mandala as a basis for unstructured “happenings” that include the active participation of the audience. Biggers’ artist bio highlights his interest in the “study of ethnological objects, popular icons, and the Dadaist tradition to explore cultural and creative syncretism, art history, and politics.” The re-use of Mandala of the B-Bodhisattva, as with much of his work, references other traditions, language, symbols, art and articles of exchange that make up different cultures. Regarding the ethnological aspect scholar Michel de Certeau contends that while social science possesses the ability to study a variety of domains and areas of exchange that make up a culture, it lacks a formal means by which to examine the ways in which people re-appropriate them in everyday situations. In the activity of re-use of Mandala of the B-Bodhisattva lies an abundance of opportunities for various audiences to subvert the rituals and representations that institutions may seek to impose upon them.

Certeau writes about discourses that present themselves as “arts of making this or that,” i.e. practices related to urban spaces, utilizations of everyday rituals, re-ruses and functions of memory through the “authorities” that make possible (or permit) everyday practices and so on. Sanford Biggers and artists such as Rashid Johnson, Mark Bradford and Fred Wilson explore this notion of “everyday practice” and the “making do” aspects of contemporary artistic production. This idea also aligns with Biggers’ “stream of consciousness” video that he played at the start of his Emory talk.

I like to think of these nonlinear videos as visual or conceptual non sequiturs and the idea is to engage the viewer; to let them put the pieces together; and give them the freedom to put the modules of ideas together in whatever order they want. I want to put things out there not to give an answer but to help people ask better questions. – Sanford Biggers

During the Peer Learning Session I referred to specific aspects of this narrative to highlight his use of colored sand painting to create Om II, his graffiti version of a Sanskrit symbol; the juxtaposition of krump street dance movements that are similar to African tribal dance; and Mandala of the B-Bodhisattva II that merges the symbolism of the Mandala with the “seriousness and discipline” of breakdance. Biggers confirmed that the “hip-hop ethos,” or the characteristic spirit of hip hop culture is very much a part of his process and permeates throughout his work, as do his Buddhist teachings. As Alembik writes,

Sanford Biggers’ ideas are derived from his passion for syncretism, the merging of seemingly disparate aspects of cultures. […] The artist himself was a practitioner of breakdancing while he was a kid growing up in Los Angeles in the 1980s. He came to the link between the two while observing Buddhist monks during time spent living in Japan. His mandala floor is activated by dance.

Mandala of the B-Bodhisattva II was initially used as a breakdance floor for a Battle of the Boroughs competition. Like the ontology or “figured world” of graffiti/street art, Biggers’ work often relies upon found artifacts, or a shared repertoire of contexts, ways of doing, saying and acting, as well as the specific use of material and non-material objects/ideas ordinary people use on a daily basis. Alembik notes the “fluid tradition” of the mandala that takes on many forms and processes. This fluidity is expressed not only in different art forms, personal, or social contexts, but also in the creation of complex artistic and intercultural contradictions.

Contemporary Mandala: New Audiences, New Forms at Emory Visual Arts Gallery, with Mandala of the B-Bodhisattva II (2012). Photo by the author.

Never one to settle into one domain or discipline, Sanford Biggers extends his exploration of found objects and complex ideas in another exhibition at Mass MoCA. The Cartographer’s Conundrum, a multi-disciplinary installation inspired by artist and scholar John Biggers (1924-2001). In this work Sanford Biggers studies and expands upon Afrofuturism, which “engages science-fiction, cosmology and technology to create a new folklore of the African Diaspora” while at the same time illuminating the underrepresented career of John Biggers. The Mass MoCA show is my next stop on a journey through the Sanford Biggers puzzle – i.e. as a new approach to production that encourages a collaborative exchange between contemporary art, culture, science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM).

Contemporary Mandala: New Audiences, New Forms is on view at Emory through April 15. The Cartographer’s Conundrum is on view at Mass MoCA through fall 2012.

Pingback: Sanford Biggers’ Codex Navigates the Past, Present and Future | Art21 Blog

Pingback: Sanford Biggers’ Conundrum: The Mothership Lands at Mass MoCA | Art21 Blog

Pingback: Cauleen Smith: A Star is a Seed, A Seed is a Star | Art21 Blog

Pingback: Cauleen Smith: A Star is a Seed, A Seed is a Star | Uber Patrol - The Definitive Cool Guide

Pingback: Sanford Biggers Studio Visit in NYC « SL Art HUD Blog Thingie:

Pingback: Shuffle, Shake & Shatter Residency with Sanford Biggers | SL Art HUD Blog Thingie:

Pingback: Imagining Building & Creating: From a Director’s Perspective to a Collector’s Home | SL Art HUD Blog Thingie:

Pingback: Master of Fine Arts Degree vs. the Practicing Ph.D. | Renegade Futurism

Pingback: How Artists Tinker: Re-branding STEAM Learning | Renegade Futurism