It seems that in the past year the subject of political art, after a long hiatus, has returned to the forefront of art discourse. Political sentiment and popular discontent have awakened in ways unseen since the AIDS crisis of the 1990s. We live in a politically charged time, where art again is looking for content outside of itself. The Occupy movement has no doubt adopted strategies familiar to art discourse, from those of the Situationists to Fluxus.

In major museums, exhibitions of political art abound, from MoMA’s 9 Scripts from a Nation at War to the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago’s This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s, and even the Tate Modern’s Photography: New Documentary Forms, in which photographers focused on subjects such as the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, or the elections in Congo.

David Hammons. "How ya like me know?" 1988. Photo: Tim Nighswander / Imaging4Art. From the MCA exhibition "This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s."

As an artist who skirts the territories of fine arts, social justice and political engagement, I am always looking to other artists that are in one way or another looking outwards to society for their content. Though the aforementioned exhibitions are rich in their breadth and certainly helpful to my practice, I found more compelling modes and explorations (and examples of political strategies) elsewhere, namely within the Art Institute of Chicago’s Light Years: Conceptual Art and the Photograph exhibition.

“Light Years” does not adopt a political angle overtly; instead it purports to function as a sort of retrospective on Conceptual Art, with a focus on the medium of photography. Strangely, the lack of a political framework allows viewers to read the work in all of its nuances, instead of being limited by an activist label already attributed by the exhibit’s context. It would be useful at this point to offer a working definition of political art. I understand political art to be art that looks out to society for content, and then establishes a space for conversation to investigate social issues. In the MCA’s “This Will Have Been” the examples of that conversation are in most cases pretty straightforward. Artist carry a message that they want to spread, or a social paradox they want to expose, with the goal of creating change. In some cases they even attempt to solve concrete problems, such as with Krzysztof Wodiczko’s Homeless Vehicle Project, where the artist modified a shopping cart to better suit the needs of a homeless person trying to survive in the streets.

Krzysztof Wodiczko. "Homeless Vehicle, Version 3," 1988-89. Courtesy Galerie Lelong, New York, © Krzysztof Wodiczko.

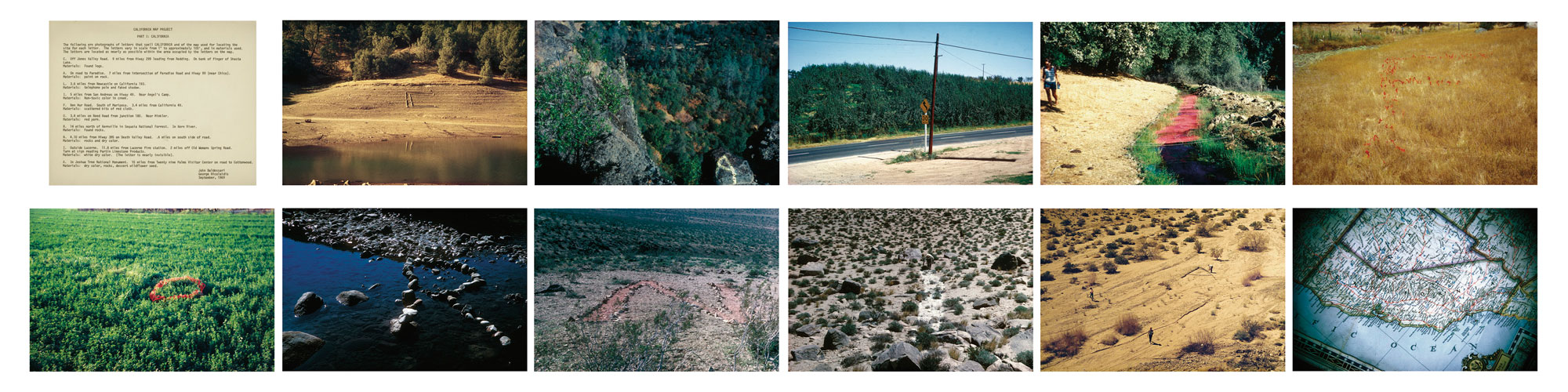

In the exhibition “Light Years,” the politics of the work are more subtle, and sometimes even appear absurd. There seems to be a common philosophical current among in the artists included in the show, where poetics are used to point out the arbitrariness of the society we live in, and the rules of normality we take for granted. In John Baldessari’s [see Season 5 of Art in the Twenty-First Century, Episode “Systems“] The California Map Project Part I, for example, Baldessari recreates the word “California” in real space, trying to match as closely as possible the letters as they appear on a map of the state of California. There is no heavy-handed pointing to politics, borders, territory, or property, but all of these things are nevertheless part of the work’s content.

John Baldessari. "The California Map Project Part I,"1969. Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York and Paris. ©John Baldessari.

In the same way, Eleanor Antin‘s [see Season 2 of Art in the Twenty-First Century, Episode “Humor“] 100 Boots from 1971 steers clear of a political message, although the military connotations of boots, and the ominous, though humorous visual effect they have when lined up can easily be read as a comment on the Vietnam war and U.S. militarization.

Elanor Antin. "100 Boots," 1972. Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York.

In a historical time fraught with an overabundance of messages, and where social justice efforts have adopted aggressive marketing tactics to spread their own message, perhaps a precious space is needed for poetics and subtlety. To borrow from Francis Alys, sometimes doing something poetic can become political, and sometimes doing something political can become poetic.