I never expected to be working on a TV show, much less one that’s based on my own life, but that’s what seems to’ve happened.

Since last summer I’ve been meeting with filmmaker John McNaughton to talk about my cabdriving career. I met John through Chicago artist Tony Fitzpatrick, who I had the the pleasure of chauffeuring around town for a couple of years; they’re friends from way back. I’ve been a fan of John’s movies since my high-school days at the Coolidge Corner Theatre, where we were one of the first places in the country to give his debut Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer an extended run. The way that film implicated the audience in the gruesome doings of its characters has never left me. To meet the guy who made it and to end up working with him wouldn’t be anything I could’ve ever dreamed up. I’ve never dreamed up much of anything in fact, doing my best work directly from life.

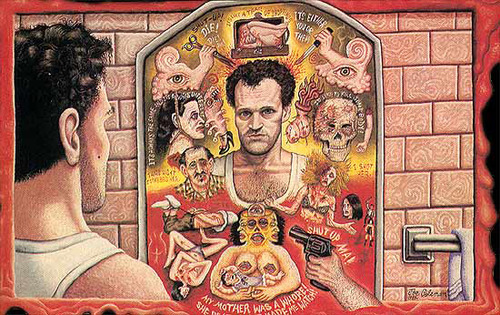

Detail from Joe Coleman’s very rare, banned, original one-sheet for the film "Henry: Portrait Of A Serial Killer" (1986).

I never even intended to write except that I kept seeing things driving a cab that I couldn’t get down in my sketchbook. I had to start using words. These words eventually turned into a book and the book caught John’s attention. Tony had been saying that Hack: Stories from a Chicago Cab should be turned into a movie or play for most of the time that I drove him around. When people say things like that you tend to laugh them off. When an actual filmmaker approaches you it’s another thing altogether. The first few times we talked about it, it was indeed about a possible feature film. The trouble is that there is no beginning, middle, and end to my book (or much of my written work for that matter.) It’s episodic and fragmentary and can’t truly be otherwise unless I start to embroider or invent. I observe people for random moments rather than neat and tidy story arcs. It would be difficult to make a traditional narrative film out of these disparate bits and pieces. After a time John decided that a TV series might work better.

My book doesn’t really have a plot as such and a TV show generally has to have one of those. Recurring characters are a help. A protagonist doesn’t hurt either and toward that end John would ask autobiographical questions. In my own writing I’ve taken pains to keep myself off stage, to stay an observer, whenever possible. This wasn’t possible here. The cabdriver had to be based on me so my job became to fill in the gaps in the story that John was writing. It’s been an odd and interesting process. To see parts of one’s biography play a part in a larger fiction is a thing that’s tough to wrap one’s head around at times. As we’ve gone deeper into it however, the cabdriver becomes his own creature, albeit with many attributes from my past.

A few weeks before I moved out of my old apartment on 24th Street—the one in which I wrote and illustrated most of Hack—John came by with his production designer, Rick Paul, and they shot a bunch of pictures, took measurements, and asked many questions. All of it with the aim of perhaps recreating a version of my place on the set of our show (should it ever come to pass.) I felt like a subject for the first time in my life. Being watched instead of doing the watching.

People John and I both know or have known have started appearing in the pages as well. I’ll ask John how he named someone and he’ll tell me a whole story about some kid he knew who’s now long gone. Using his name is a way of paying tribute. Tony’s playing a large part as well—or someone very much like him. How could he not be? He always wanted to be written about in Hack but I’d never do it. One of my rules in my cab writing is not to write about anyone I know. There I’m not interested in embarrassing anyone explicitly or losing friends, which would undoubtedly happen if I were to write about them. In this new fictional context we can take aspects of those we know and the places we’ve been and weave them into the story in a way that’s not available in nonfiction. The Roseland neighborhood that John grew up in has made its way into the story, as have many of the places I’ve been to in this city. In this way he’s making the world of the show out of our worlds. I suppose that’s how all fiction comes to be.

Being used to working alone, it’s hard to imagine being involved in something as grand as a TV production. I hope it happens. The Chicago I know has rarely been seen on screen. I’d like to see it.

Pingback: Dmitry Samarov On Having His Life As A Hack Fictionalized By John McNaughton « Movie City News

Pingback: Words and Pictures for Other Places | Art in its Own Terms