Exhibitions are not created within a vacuum; instead, they are triggered by timely events, local movements, and fictional stories. It has become a common occurrence to curate a show based on a work of literature. The Wattis Institute in San Francisco, CA comes to mind with their recent trilogy of exhibitions based on canonical American novels — Moby Dick, The Wizard of Oz, and Huckleberry Finn. All three of the catalogs produced for this trilogy have used early editions of each novel as inspiration. Although these catalogs are visually captivating, they use the themes and aesthetics of the novels when useful, and infuse their own hand to align each novel with its corresponding exhibition.

Almost all exhibitions relate the works in a show to external influences, but few have used an influential text the way the Purtill Family Business did with their catalogue for the New Museum’s 2008 exhibition, After Nature. On their website, the Museum described the exhibition as follows:

“After Nature” surveys a landscape of wilderness and ruins, darkened by uncertain catastrophe. It is a story of abandonment, regression, and rapture—an epic of humanity and nature coming apart under the pressure of obscure forces and not-so-distant environmental disasters. Bringing together an international and multigenerational group of artists, filmmakers, writers, and outsiders, the exhibition depicts a universe in which humankind is being eclipsed and new ecological systems struggle to find a precarious balance.”

The exhibition’s publication addressed an equally interesting question: can an exhibition catalog exist within the pages of its reference material?

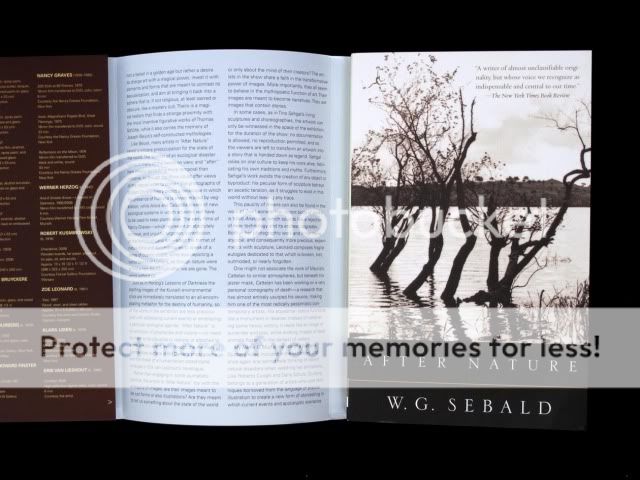

After Nature, 2008. Image courtesy of Purtill Family Business.

After Nature, 2008. Image courtesy of Purtill Family Business.

Curated by Massimiliano Gioni, the exhibition not only utilized the themes and title from W.G. Sebald’s After Nature, but Sebald’s book also became the “site” for the exhibition catalog. Re-purposing Modern Library’s 2003 pressing of After Nature (128 pages), the book contains loose 6×3.5 inch reproductions of the works in the show and a six panel fold-out dust jacket that houses the exhibition credits, acknowledgements, and curator’s essay. When the exhibition was organized in 2008, there had already been several recent cataclysmic natural disasters across the planet; tornados and floods tore across Iowa, while China experienced unprecedented earthquakes and cyclone Nargis devastated Myanmar with 138,000 fatalities. Like Sebald’s three protagonists, the artists in the exhibition [full listing here], each express a sense of anxiety and unease about nature and their own place within it.

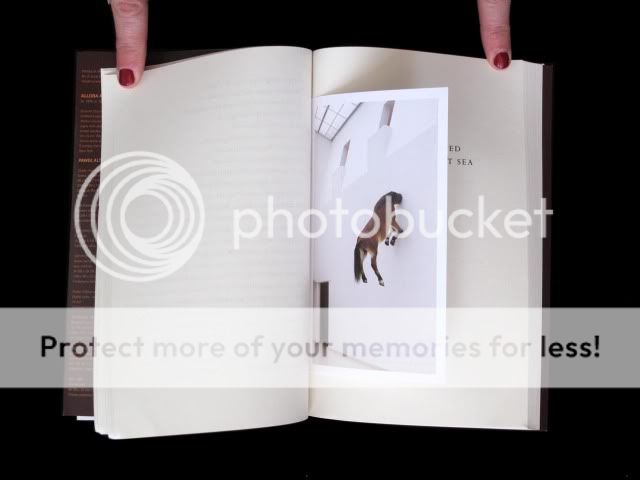

It’s odd that the way I have read this catalogue mimics the way tornados jump from one town to another. The thin, postcard-like plates that are inserted every two to three pages of the publication provide a bookmark-like feel that left me “jumping” every few pages to scan both the images and the texts. I am not sure how the order of the plates within the book was determined, but I often found myself linking small bits of text with the image of the art object inserted between its pages. At times that creates puzzling yet humorous pairings: for example, an image of Maurizio Cattelan’s taxidermied horse (pictured below), which in the exhibition is installed roughly seven feet off the floor with its head through the wall, is inserted next to the words “and if I remained by the outermost sea.” The pairings are a bit nonsensical, but they provide an unpredictability and casualness that contrasts with the anxious themes expressed in the exhibition and source text.

The exhibition catalogue’s addition to the original book–the plates and dust jacket–have an interesting power dynamic with respect to Sebald’s work. None of Sebald’s text has been altered. If a reader wanted to discard the plates and jacket, they would be left with a copy of the original book that would somehow feel as if it were uninhabited, like an abandoned house. Catalogues often begin with a Director’s forward and a curator’s essay, followed by more essays and plates. Although it is easy to read the catalogue for After Nature in this linear fashion, it would be just as easy to skip over Gioni’s words and begin reading Sebald’s text instead. At times, it even feels as if the catalogue puts more weight on Sebald to contextualize the art in the exhibition, instead of on the curator Gioni–which leads me to think that either Gioni has the utmost respect for Sebald’s work, or felt his own sense of anxiety about the influence of his source material.

After Nature, 2008. Image courtesy of Purtill Family Business.

The New Museum described the re-purposing of existing copies of the original “an homage to W.G. Sebald,” but to me, the gesture goes beyond that. Purtill Family Business and the New Museum radically redefined the way exhibition publications use the materials that have inspired them. Gioni’s exhibition After Nature is absolutely reliant on Sebald’s book After Nature to provide additional context to the ideas in the show; in turn, the catalogue is contingent on the physicality of the book that houses it.

The catalogue for After Nature offers a unique example of how to re-use existing printed material to create new forms; it also engages art’s longstanding infatuation with found objects in an innovative way. The consistent thread of anxiety running throughout the exhibition’s works, as well as in Sebald’s writing, is remarkably muted when encompassed in the publication’s final form. All of the swirling thoughts and worries expressed in the show are neatly contained within a package that’s not only really cool to look at, but also evokes the proverbial feelings of calm before a storm.

Pingback: Bound | After Nature | Benjamin Phillips