“We probably went to the same art parties,” says artist Jeffrey Vallance to artist Thomas Kinkade in a video from eight years ago. The two sit together on a stage at Cal State Fullerton, and have just established that Vallance would have been a student at California Institute of the Arts around the time Kinkade was studying nearby, at Art Center in Pasadena. “That’s where I know you from,” says Kinkade, joking. Just a few moments before, he has announced that he feels he’s known Vallance most of his life. In fact, the California artists met earlier that same day, when Kinkade arrived to see Heaven on Earth, the show Vallance curated about The Painter of Light and his massive inventory. It was the first comprehensive Kinkade show to appear in an “art world sanctioned” museum. Now the two are taking questions at a press conference, at which Vallance thanks Kinkade for giving him complete freedom and Kinkade thanks Vallance for being thoughtful.

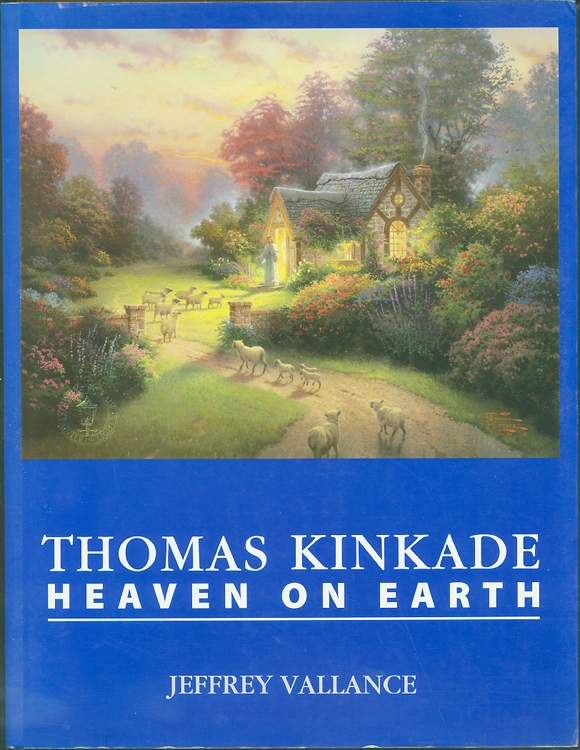

When Kinkade first heard about the show, he “told our staff . . . all this is going to be is a chance [for them] to play this whole thing for irony and turn me even more into the whipping boy of the critical elite.” He had expected the show to try to prove his oeuvre “is obviously kitsch.” Instead, Vallance’s show felt serious–“it’s realism,” Vallance says. It takes sensitive, encyclopedic stock of a cultural phenomenon. Vallance has culled together paintings, bath towels, figurines, music boxes, even constructed a living room and a chapel out of Thomas Kinkade “designs.” “The fact that this exhibit enshrines those [items] in a Fine Art setting is brilliant,” says Kinkade.

Sitting next to Jeffrey Vallance, an artist with insatiable curiosity and an even-keeled, impenetrably low-key demeanor, softens Kinkade. He seems savvy, even likable, and only grating and misguided part of the time, like when he says, “I paint pretty pictures that are homespun, non-threatening imagery, and the London Times calls me the most controversial artist in America.” He may have been the most controversial artist in America, but his images are not really just “pretty.” They “are quintessentially picturesque,” wrote Doug Harvey in an essay for Vallance’s show that Kinkade likely read, “That is, they are pictures that look like scenes that look like pictures.” Nor are his images of quaint cottages “non-threatening.” Joan Didion, in an essay that’s been quoted incessantly since Kinkade’s death last weekend, called them sinister, “suggestive of a trap designed to attract Hansel and Gretel.”

Installation view of "Heaven on Earth" at CalState Fullerton's Grand Central Art Center. Courtesy GCAC.

However, Kinkade may not be misguided when he says, “I’ve achieved the Nirvana that Andy Warhol dreamed of achieving. . . . Andy Warhol’s dream is that he would become a robot, just push a button and the paintings would come out. I’ve done that.” And he’s mostly right when he says, “You’re going to reap what you sow. If you’re an artist who’s very idiosyncratic then. . . . the audience and market for your art will be limited.” Kinkade was militantly against idiosyncrasy — everything he made, even if unbelievable, was controlled and predictable in its sappiness — and his market was sprawling, mind-bogglingly so.

Two weeks before Kinkade’s death on April 6, I was asked to remove a reference to him from a catalog essay I was writing. I do not resent this. I understand that many artists and, more so, institutions fear proximity to him, the painter who made commerce a kind of evangelism and sentimentality a cultish religion. But sometimes he is the best reference to use when trying to describe how a dreamy idea of coziness could be pushed to mind-numbing extremes, or how culture can be baffling. Novelist Zadie Smith said what she wants to be “confronted with is exactly what is radically not me, a consciousness of the world that is so far from my own, it’s a shock.” Shying away from Kinkade references means downplaying what I think is one of the greatest goals of art: to put us in touch with experience profoundly different from our own.