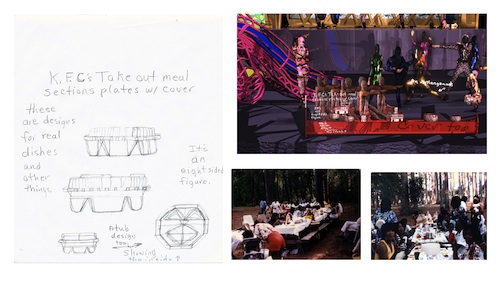

Jacolby Satterwhite. “Country Ball 1989-2012, Appendix (detail),” 2012. Digital video & 3-D animation. Courtesy the artist.

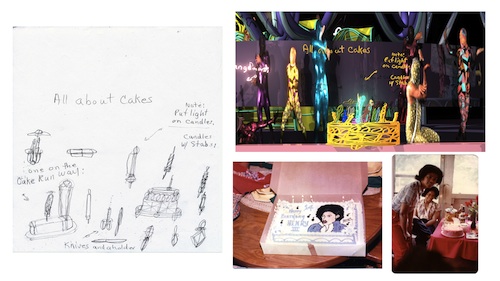

In Country Ball 1989–2012, Appendix, a new performative video and 3-D animation from artist Jacolby Satterwhite, cakes are not delicious desserts but strange architecture. Some spiral up like Towers of Babel and their tiers serve as platforms for performance: Satterwhite appears on top of them — in multiples of himself — posing, swaying, bouncing, voguing. Other cakes peak like roller coasters and add to the general spirit of amusement park here; a phallic carousel slowly rotates at the center of this cakescape. In one scene Satterwhite werqs a “cake runway.” Occasionally, his body spurts neon-colored fluids. It’s unclear what these substances are but breast milk, cum, and frosting can’t be too far fetched. Cake is one of many pleasures in this sort of queer candy land, where idealized male bodies toil and play alongside the artist. What’s most extraordinary about this world Satterwhite has created is how his family figures into it.

Jacolby Satterwhite. “Country Ball, Appendix (detail),” 2012. Digital video and 3D animation and screenprints on Coventry paper. Courtesy the artist.

On view at the Studio Museum in Harlem, Country Ball incorporates video footage from a 1989 Satterwhite family cookout along with drawings made by the artist’s mother, Patricia Satterwhite. It’s implied that a product of her ongoing mental illness is a compulsion to draw. Since Jacolby’s childhood, Patricia has created over 10,000 schematics for clothes, jewelry, utilities, and foods. Those curious cakes and other objects we see in Country Ball represent 35 of her designs, digitally traced by Jacolby and then made into 3D models. He limited himself to Patricia’s drawings of cookout materials: cakes, watermelons, fast food packaging, aprons, barbecue grills, pots and pans, playground structures, a lemonade pitcher, a jeep. In Country Ball some of these larger objects function as projection screens for the cookout footage. But more than we actually see that event, we hear its mixtape soundtrack and the joyous cacophony of family. Jacolby likens the process of putting these various pieces together, and essentially “reperforming the cookout,” to playing a game of Exquisite Corpse:

“My method of putting together the narrative is very strange. I write down key words that are in the drawings, [my mother’s] text, and then I give myself two minutes to write down a concrete poetic essay. Then, when I go to the animation drawing board, I have to actually execute what I wrote in a stream of conscious way. It’s the same way with my movement, or the improvisation dancing that happens in my studio. I go into the green screen and I do four hours of improvisational dance that’s influenced by modern dance and voguing. Then I take all that footage to the computer, I trace all my limbs, and I think, how does my movement and body inform these objects and world that I’ve created, and how can I string it together in a nonsensical fashion?”

Jacolby’s surrealist mindset allows no conflict between lived experiences and imagined ones, fantasy and actual fulfillment. Country Ball seems a boundless space partly because any boundaries that might exist between Patricia’s naïve pencil drawings and Jacolby’s glossy video game aesthetics, between grainy footage of the Satterwhite family dancing in the 1980s and the artist’s costumed movements in a modern-day high-tech studio, have been erased. One form feeds another.

Voguing is in fact drawing for Jacolby. It’s a means of creating angels and lines with his body and of, again, referencing the matriarch. In the “houses” of ball culture, where voguing developed, that role is performed by a leader, “some ‘mother’ who’s trying to take care of you, or trying to mimic Western patriarchy,” he explains. Too, ball houses are modeled after fashion houses and their younger members might act as apprentices or understudies. Jacolby has long seen himself as an apprentice to his mother, who envisioned her objects as the products of her own designer fashion house, The House of Patricia:

“My mother had an insomnia problem when I was a child and she was up at night watching infomercials. There were a lot of commercials in the 90s about manipulating the viewer into believing that they could become an inventor … She was also a big fan of The Bold and the Beautiful on CBS, where Sally Spectra and other characters had fashion houses … So my mother was sending her drawings off to the Home Shopping Network and QVC and, due to her illness, she assumed that things were happening. Her instructions were intended for patentors … I wanted to help her so I started to learn how to draw. I kept trying to get better and eventually I started making my own drawings and moved into my own artistic discipline.”

Although Jacolby operates in an academic context today, by repurposing his mother’s drawings he effectively merges their “insider” and “outsider” practices. Synthesization is a tactic that serves many purposes for him. For one, it reduces opportunities for gendering Patricia’s work, as he often sees happen for women artists. It also allows him to expand on — or refuse — existing identity discoures and imagery. For instance, “queer” in Country Ball “doesn’t rely on tropes involving transgressive roles in sexuality,” says Jacolby. But introduces, he hopes, a new model for queer art.

Jacolby Satterwhite, “Country Ball” installation at the Studio Museum in Harlem, 2012. Digital video and 3D animation and screenprints on Coventry paper. Courtesy the artist.

Jacolby Satterwhite. “Country Ball, Appendix (detail),” 2012. Digital video and 3D animation and screenprints on Coventry paper. Courtesy the artist.

Country Ball is one of the better installations in the exhibition Shift. The work feels fresh but also vaguely familiar, bearing resemblance to the artist’s recent video animations Reifying Desire. These too are based in Patricia’s drawings though, for Jacolby, his Studio Museum installation is “something completely different.” His concentration on foodstuffs here is an obvious distinction. Flanking the video projection are framed screenprints of Patricia’s drawings (one of them is of cakes) and some family snapshots (some of which picture cakes). Why the emphasis on these confections? Jacolby has seen colleagues frequently respond to them, and curious about their reactions, he decided to make a cake cityscape. “I thought, why don’t I really push the absurdity of the narrative, find a way to repurpose these objects, and queer their functions?” By projecting himself dancing on top of cakes, he plays up their pleasurable and celebratory nature. More than fulfilling any dietary need, cakes satisfy our desire for decadence and gratification. “Excess and capitalism is the American Dream,” the artist has said. “I am a victim to desiring complacency and comfort.”

Near the end of Country Ball he attempts to vogue on top of a cake, but ropes are tied to either of his wrists and male figures simultaneously pull him in both directions. At one point, that artist stops resisting their pull and despondently buries his face in cake. Patricia’s drawings of money, credit cards, wallets, crowns, and a picket fence — ideals of the American Dream — soon materialize, and the narrative shifts from being about pleasure to, apparently, the downside of having too much of a good thing. (In the exhibition brochure, essayist Thomas Lax makes apt reference to Hieronymus Bosch’s triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights, c. 1490; one side shows paradise and the other, hell.) In the climactic final scene, a prostrate male figure consumes everything around him and Country Ball collapses into a sort of black hole. “Country Ball is generally about greed,” says Jacolby. “But it’s also about recreation, ritual, family.” He pauses. “It’s about a lot of things.”

Country Ball 1989-2012, Appendix is on view at the Studio Museum in Harlem through May 27, 2012. New works by Satterwhite will be on view at Monya Rowe Gallery in June.

Pingback: Gastro-Vision | Queer Cakes for a Country Cookout | 全球汽车与工业设计资讯

Pingback: Gastro-Vision | The Best in Food-Art 2012 | Art21 Blog