Not only is Meg Onli a regular columnist for the Art21 Blog’s Bound: The Printed Object in Context, she is an artist and writer living in Chicago who founded and runs the blog Black Visual Archive, “a collection of critical writings that contextualizes the work of African American artists through cultural and visual history.” A graduate of The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, she was recently selected to participate in the Creative Capital/Andy Warhol Foundation’s Art Writer’s Workshop. I talked with Meg about the genesis of Black Visual Archive and the direction the project will take in the future.

Terri Griffith: What was your catalyst for starting Black Visual Archive? What kind of scope did you have in mind?

Meg Onli: I had been working at Bad at Sports for four or five years when I decided to start my own project. I wanted to hone my writing skills and use the new blog as a way to funnel my research. Racial politics and the performance of race had been subjects I had been exploring in my art and I wanted to run a website that had a very specific focus, so it felt like a natural transition to write about art created by African American artists since they were the artists I was always looking back to. There are a lot of amazing art blogs that cover contemporary art in every major city but there were not many that covered work created by black artists so I saw an untapped niche and decided to just jump in.

BVA’s scope was pretty broad when I started — I mainly wrote about anything that I was interested in. Right now I am participating in Creative Capital/Andy Warhol Foundation’s Art Writers Workshop, working one-on-one with a mentor, and that has focused me more. Most of my research right now is based around the rise of black representation in American media during the 60s and 70s so I can see where my recent posts have been reflecting that. I am working on a research paper on the photographer Ernest Withers in relation to the 2010 release of information detailing his role as an FBI informant from 1968 to 1970. I am really interested in what it means that the images that defined us in the 1960s can also be considered surveillance photography for the U.S. Government. So, I can see more of my writings focusing on this.

TG: Much of your practice focuses on this kind of documentation and archiving. What’s your interest in these methods and how does BVA play into this? Do you consider BVA itself a work of art?

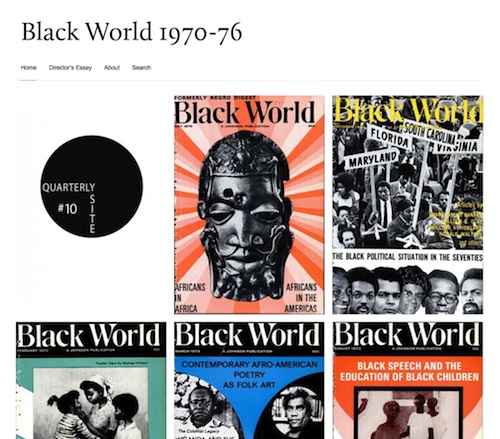

MO: I do not necessarily frame BVA as an artwork so much so as a vehicle to document my current research. In the past few months I have focused my efforts on representing what is happening in Chicago. Chicago has a rich history within black visual politics and it is surprising how many contemporary artists have roots in the city. I see BVA documenting the works of these artists but also cultural establishments like Johnson Publishing Company or Numero Group as well. We were recently asked to curate a show for Quarterly Site and I decided to focus on organizing an archive of a Chicago group/organization. The project is called Black World 1970-76. I’ve been thinking a lot about the period right after a social movement has occurred and wondered if there was a definitive time when the civil rights movement ended. Google has created a comprehensive digital archive of the Johnson Publishing Company where you can access copies of Jet, Ebony, and Negro Digest (later named Black World.) I thought Black World/Negro Digest always had a more political point of view so I decided to look at the years following Martin Luther King’s assassination (what many claim to be the end of the civil rights movement) to see if there is a shift in the way writers were framing events of the black power and civil rights movements.

When looking at these articles there becomes an obvious transition in the way people are discussing black life in the 70s; you see a call for preserving black culture in a time of assimilation, varied states of reflection of the past decade, as well as a sense of determining new struggles in the constantly evolving fight for equality.

TG: One of the most distinctive things about BVA is that you allow room to explore a single idea leisurely and from more than one perspective. For example, in your consideration of Adrian Piper, you have three essays written by Martine Syms, Andrew Blackley, and yourself. This allows the reader to immerse herself in an artist and look more deeply into the work. In your essay you discuss the novella Passing by Nella Larson and also link to Piper’s essay “Passing for White, Passing for Black.” It seems you expect a lot of your readers.

MO: Most of my writing for BVA aims to give a historical context for the work I am discussing but I do not necessarily expect every reader to know all of my references. What I would expect, or at least hope for is that my readers bring a sense of curiosity to the subject of black visual culture. I think that is what I liked most about the Piper series. When Andrew asked me about writing a piece for BVA on Piper’s work I had been reading several of her essays as well. It was interesting to see that this artist was on our consciences and we collectively wanted to explore her practice from three different viewpoints. Exploring ideas at a leisurely pace really appeals to me, it allows more time for research and reflection without the pressure of turning something out quickly. Aspects of Todd Sieling’s “Slow Blogging Manifesto” intrigued me when I first created BVA. At the time, I was really entrenched in Twitter and was overly concerned with what was popular and new. I became burnt out and wanted to find a way of writing that would be pleasurable again. BVA is a lot of work but I really enjoy what I am doing and doing it at a pace that allows me to flesh out my ideas.

TG: You mentioned the Ernest Withers research you are doing. Are you working on anything else right now?

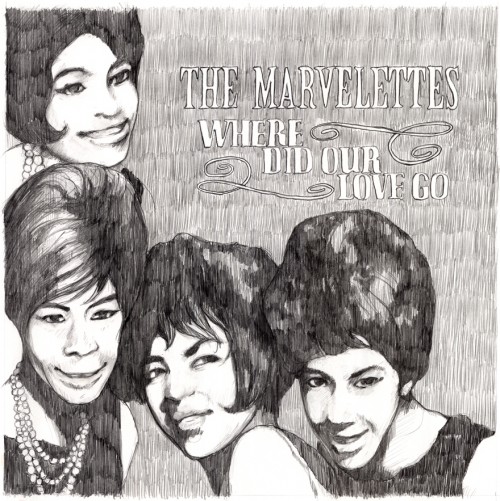

MO: Yeah, I am working on a longer article that should hopefully post in June called The Marvelettes, Where Did Our Love Go? I was doing a studio program in 2007 when I read about Motown’s first sensation the Marvelettes–who are most known for their song Please Mr. Postman— turning down Holland–Dozier–Holland’s song Where Did Our Love Go? before it was given to The Supremes. Obviously the song was a huge hit for The Supremes but I was really interested in this alternate history of, “what if the Marvelettes had recorded the song?” When I started reading about the two groups I started to create a large US timeline to understand the climate the nation was in. I began to see a correlation between historical events and the popularity of the groups’ songs. For instance, when Please Mr. Postman was released America was still fighting the Vietnam war. People were waiting to receive letters from their loved ones and members of the Marvelettes saw that event as the reason the song resonated with its audiences. When you look at the moment when Where Did Our Love Go? was released the Civil Rights Act of 1964 had already been passed. I want to see if maybe America was ready for a black singing group to dominate the Billboard Pop Charts? Needless to say, I am interested in how history shapes the relevance and popularity of the music that we listen to. I wanted to be able to write a piece that could rely heavily on a timeline to give context to each song’s popularity. I’ve also worked with an illustrator to provide some alternative album covers — sort of a way to see the Marvelettes in place of The Supremes.

TG: Do you have a sense of your audience? Are they artists? Students?

MO: You know, I do not have a clear sense of who BVA‘s audience is. Through analytics I can see where people are located but I cannot say if they are artists or students. I would love to think that stereotypically righteous professorial types and hip post-racial artists are reading BVA but I also see people like my mom, someone who may not read about visual culture but understands its complexities through raising two bi-racial queer-identified daughters, interested in what I am writing about. I guess I would like to think BVA’s content, although about black visual culture, speaks to people in many different demographics.