Leeza Ahmady is originally from Afghanistan. She is an independent art curator and educator from Central Asia. She is based in New York and, as the director of Asian Contemporary Art Week (ACAW) at Asia Society (2005-present), Ahmady brings together leading New York City museums and galleries to participate in special exhibitions, receptions, lectures, and performances citywide.

Ahmady’s name is directly linked to The Taste of Others project, which began in 2005 and continues to feed her practice to this day. A performance-based exhibition first launched at Apexart New York, The Taste of Others is an on-going educational program that connects contemporary artists from Central Asia to artists, professionals, and institutions in other parts of the world.

Through Dialogues in Contemporary Art (DCA) in collaboration with Independent Curators International (ICI) and ARTonAIR.org, Ahmady conducts interviews with artists, curators, critics, and experts working across a broad field of contemporary art. The program addresses the role of artists, curators, and other art professionals in an increasingly borderless world, investigating the ways in which artistic practices, curatorial strategies, and critical commentary have been reconfigured by intensified patterns of global circulation.

Most recently through her role as an agent and member of the curatorial team for dOCUMENTA(13), Ahmady traveled to Kabul in February 2012 to present a series of workshops in anticipation of the exhibitions in Kassel and Kabul Summer 2012. The workshops covered art theory, perspectives on international contemporary art, and the building of a critical art magazine.

Ahmady also serves as the Director and Co-curator of Visual Arts for an upcoming citywide program of contemporary art from Cambodia in New York City (Spring 2013). Through a series of artist residencies, site specific installations and public programming, the project aims to build critical spaces of engagement with contemporary artists and practices from Cambodia.

There is so much more to say about Leeza Ahmady, and for that reason please make sure and read Part 2 of this ongoing discussion, which will post next month. Perhaps of all the interviews I’ve done for this column, I’ve found the greatest inspiration in Ahmady’s sense of dedication. It’s an honor to present to you independent curator Leeza Ahmady.

Georgia Kotretsos: For someone who claims to always be working with a map–and I’m referring to myself–as I had casually accepted the marginal role in art that a big part of the known world is said to play. I am speaking about Central Asia: Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan & Afghanistan. At the March meeting 2011 in Sharjah, you generously shed light on my obliviousness, and today, I am inviting you to start our discussion by taking you back to the very beginning of your extensive research and curatorial work. What motivated your interest in these regions?

Leeza Ahmady: History is a remarkable instrument for comprehension. Let us consider the term “marginal;” how stable is it as an idea in retrospect to history? Much of what was deemed “marginal” at some point in the past is mainstream today; i.e. the Impressionists, Dadaists, Performance Art, Chinese contemporary art, and so on. Beyond human reckoning, this is universal physics. Pendulums swing in different directions. That which is marginal shifts to the center, and vice versa.

I prefer the term periphery; it acknowledges complexities of this world where the art world itself is peripheral. In my years of work in the field, I have come to view the art world as a giant fragmented and unconscious machine incapable of discretion. Let’s think about this: can an unconscious body consciously marginalize? It is the individuals who make a difference, and so much depends on awareness. To become conscious of something different, beyond what we already grasp, we must make a different kind of effort. Questioning one’s own intellectual and cultural programming is difficult; trying to achieve this on a collective scale is a colossal task. Yet critical observation and the breaking down of one’s conceptual mechanisms is the minimum requirement for change. As art professionals all that we do is part of the art world machinery, this interview included.

The notion that there are authorities acting in cohesion to grant or to deny opportunities underrates and belittles distinct historical time lines, experiences, and circumstances of individual artists and artist communities in different parts of the world. Indeed, museum directors, institutional curators, educators, and biennial foundations must make it a priority to more seriously and inclusively inform themselves on artistic practices worldwide. This will involve including and accounting for other geographies, histories, narratives and timelines in their respective programs. Let us not forget that Europe, for instance, boasts a healthy art system that contributed to the development and exhibition of contemporary art and artists as a result of decades of local, regional, and international collaborations and institutional relationships that began in the post-World War II era. dOCUMENTA being a prime example.

Significant things often begin in peripheries where there is room to reinvent, to take risks, to experiment and to push boundaries. My own career began in one of the peripheries of the New York art world: the club scene. I often have flashbacks of keeping art works intact from tipsy club-hoppers installed inside of every nook and cranny of the Tunnel hallways (a subway station turned mega-nightclub).

Extravaganza type one-night art events have been frequently staged in nightclubs for decades, becoming especially popular in the post-Warholian late 1990’s. But that model quickly felt insufficient when juxtaposed with the onslaught of new contemporary artists flocking to New York in the late 1990’s. Thus, inside the infamous Limelight club (formerly a church), I set out to launch three weeklong exhibitions that would be open to the public during the day. This permitted me to invite museum curators and gallery owners to collaborate on projects they would not have been able to realize at their own venues because of various limitations. Those years proved formidable in informing my curatorial practice, a great deal of which has to do with mastering the art of communication–an ability to weave a tapestry of otherwise improbable and fascinating people, concepts, and artistic practices. Ten years down the line, the Tunnel is now a legitimate art space, transformed into one of Chelsea’s sprawling new gallery complexes, while going to an opening at MoMA feels more like stepping into a wonderful nightclub. That’s a phenomenon! Was there some pioneering of a sort, or was I simply in the midst of a swinging pendulum?

Peripheries have their own sets of challenges, naiveties, and failures, so there came a moment when I had to stop and contemplate what I really wanted to accomplish. My focus on Central Asia is logically autobiographical. I grew up listening to classical music, epic tales, and poetry fused with daily political debates between my family members. From my parents, and the Afghan collective, I inherited an intense awareness of the world with the premise that it was whole and connected, and that I was at its center just as powerfully as anyone else. This hypothesis broke down upon my arrival in New York as a young teenager. Almost no one my age had ever heard of the country. It was a disappointing and baffling reality, which in turn initiated my interest in the psychological make-up of collective societies. At the age of 20, standing in front of a Giotto painting at the Uffizi, beyond aesthetics, I was floored by its liveliness, and communication. I thought “Wow, there must be artists making revealing works like this everywhere now and I want to know them.” I decided to study art and work with artists in that instant.

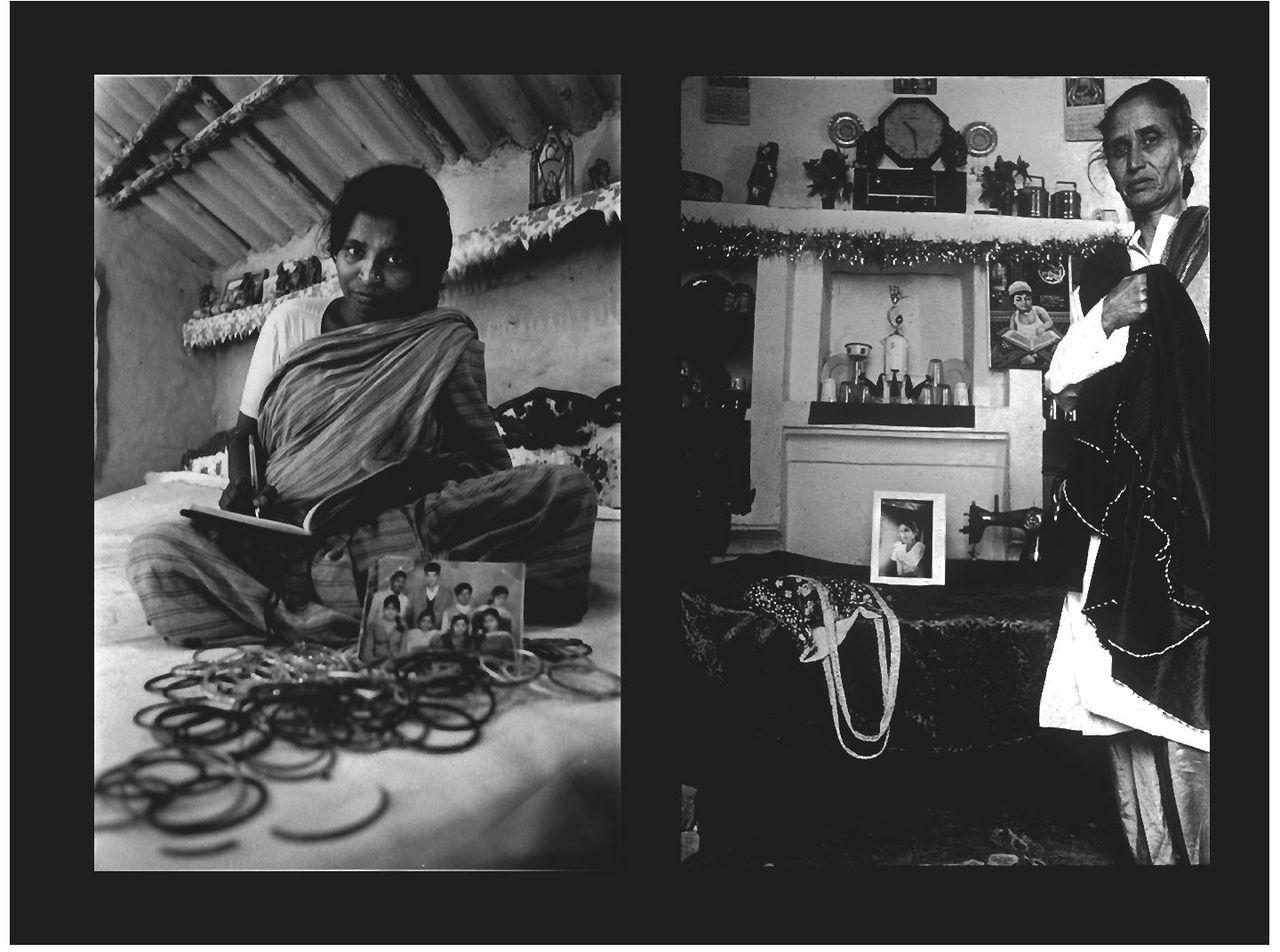

Mithu Sen. "MOU, Museum of Unbelongings," 2012. Site-specific installation, fabric and found objects. Courtesy of the artist.

GK: How did you prepare the ground for art from Central Asia in the States in the mid-’00s, after 9/11, and how did you connect the dots to Kassel in less than a decade? Is the art world perhaps redeeming itself for ostracizing creatively active regions after having followed politically-charged leads for too long?

LA: Contemporaneity, much like modernity, art, and creativity does not belong to one race, place, or economy. I wanted to look at how it happened to unfold in Central Asia. I have approached my research from a broad perspective, thinking of maps as essential conceptual tools in life. Sufism sees the universe in concentric circles radiating both inward and outward. Geography was as important a discussion as philosophy and literature in my household, as well as in school. Living in Afghanistan it was clear that I was encircled by countries that share centuries’ worth of linguistic, cultural, ethnic and spiritual ties, located within the larger continent of Asia. Looking at Central Asia inherently meant looking at other parts of the world.

Many events in the past two centuries have isolated or fractured our knowledge about artistic contributions while obsolete measuring sticks (based on East-West inferiority or superiority complexes) are still used to write art history. Art and curatorial work have become my means for experiencing the world as connected, no matter how great or minute in scale. Driving this has been a series of partnerships with artists who are transforming perceptions, filling contextual gaps, and creating access to what is otherwise inaccessible. Given that Central Asia was isolated by the schisms of twentieth century politics, I have had to tailor my own course of discovery and engagement, while connecting with colleagues that share similar ideals elsewhere. There is no doubt that some great breakthroughs have been made.

In the same manner that other formerly invisible regions in the world (South America, Africa, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, East and South Asia) have joined an explosion of transnational contemporary art activity, artistic communities in Central Asia are overcoming isolation. The process has required conscious and diligent effort by individuals inside and outside of the region–in peripheries as well as in central arenas. I have managed to act as facilitator, interpreter, and enabler of this process, which is gratifying, but there is still an enormous amount of work to be done. As you noted, in the appeal I made during my presentation at the 2011 March Meeting in Sharjah, this will require much more collaboration and support.

GK: This column has often made me consider the works of art that have never left the studio. What are those? If never shown, if an “art dart” has missed a work by a decade or longer, what do we make of that? Does art get stale?

LA: On a recent trip to Delhi and Kabul, I am thankful to several artists whose studios I visited with a renewed sense of what a studio visit means. While as a curator, it is impossible not to automatically think about how, where, and why works could be presented, I have equally accepted that this does not have to be the end result of a studio visit. We must remember that works, whether in a museum, gallery, or piled up in an artist’s studio, are primarily tools for developing art practice. Visiting an artist’s studio is like entering an artist’s mind, no matter what the setting, it is an intimate space that acts simultaneously as a creative incubator and exhibition space in its own right. Perceiving this, I find myself more open to embracing the visit as a chance to interact with an artistic practice, experiencing the rich and often delicate exchange that occurs between artist and curator as audience.

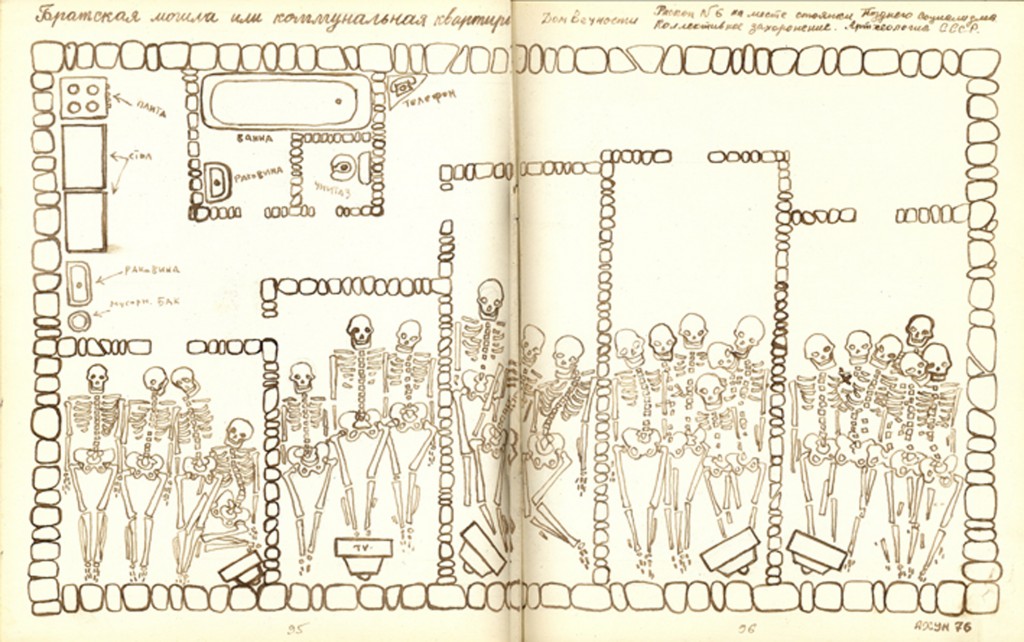

In 2004, on an extensive research trip in Central Asia, I made my rounds to dozens of artists’ studios. Particularly intriguing was that of artist Vyacheslav Akhunov in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, mainly because of an overwhelming sense that there was much more that he was not showing me. My second studio visit with Akhunov was in late 2009, this time at a café in Chelsea while he was visiting New York. What he revealed was astonishing–a never-before seen digital compendium of some 3000 pages of drawings and notes he had been actively conceptualizing in the form of notebooks since the 1960’s. For fear of persecution (Soviet and Post Soviet eras) he had kept the vast majority of this work hidden for nearly four decades. All of his works I had seen and exhibited since 2004 suddenly clicked, taking on a profound new significance. In fact, so deep was the inspiration from this second fateful studio visit with Akhunov that he is the subject of my dOCUMENTA(13) “100 Thoughts – 100 Notes” notebook contribution.

Vyacheslav Akhunov. "Art-cheology," 1976. Drawing on manuscript page. Courtesy the artist and AhmadyArts.

While the artist-curator relationship can be difficult to navigate at times, when allowed to unfold organically it can also reveal new levels of work, thought and consciousness that would be unattainable through institutional type interactions. Curatorial work to me is linking poignantly disconnected ideas and contradictory concepts to facilitate critical thinking for the public as an essential aspect of exhibition making. My practice involves framing processes that could create an experience or experiences of consciousness. This cannot be dictated by time. If a work is leaving the studio for the first time in decades, it is essentially up to the curatorial process to expose that work’s significance. More so than art, and even if we do not like to admit it, curatorial work can go stale. It is an exploratory field, and there is a level of freedom to it that we are only just beginning to test. I recognize that my role has moved far beyond the bounds of exhibition and now encompasses lectures, essays, studio visits, and even the conversation that I am opening up here.

And, that’s a wrap until next month. Stay tuned for part 2 of this conversation with Leeza Ahmady in May.

Pingback: Inside the Artist’s Studio: Leeza Ahmady (Part 2) | Art21 Blog

Pingback: Inside the Artist’s Studio: Leeza Ahmady (Part 2) | Uber Patrol - The Definitive Cool Guide

Pingback: Ahmady Arts | Blog | Interviews, Projects and Articles