It’s the end of the semester, sleep is in meagre supply and I’m writing this on May Day, just after finishing a day of teaching. I’m tired, but I feel strangely energized, wired. I went to David Harvey’s lecture this morning at the Free University (part of May Day in Madison Square Park) which I was really excited about, and he didn’t disappoint. I’m proud to be part of CUNY precisely because of great professors like him, and when he talked about the good old days of free British education (something I’ve written on already for Art 21), I almost cheered. He, like me, went to school for free (and don’t we know how lucky we are). His talk hit all the topics one might expect for May Day: the predatory practices of financial institutions, income inequality in New York, meaningful production devolving into violent speculation, and accumulation of wealth by the minority via (forcibly) dispossessing the resources of the majority. I was really proud that the first question from the audience came from one of my students, who asked Harvey what models he thought existed for the future. What was out there that could subvert or explode existing structural impasses? If not this capitalist model, he asked, then what?

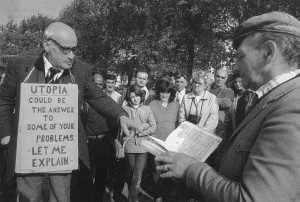

It got me thinking about the lesson I was going to teach that afternoon, one of the final classes I’m teaching this semester on the Art Market to a bunch of awesome Baruch undergrads. These students are smart, engaged, and articulate in their discussions of the history of the art market we’ve traced for this class. Although my specialization is modern and contemporary art, I’ve only ever worked for non-profits so the business side of the art world was somewhat new to me. I stepped in for a colleague who is on sabbatical this semester and have been gulping down articles and textbooks on the subject like they’re going out of fashion: Don Thompson’s The $12 Million Stuffed Shark, Filip Vermeylen on the emergence of the Dutch pands, the Herb and Dorothy documentary, Andrea Fraser on L’1%, and Oren Soltes on politics, ethics, and the repatriation (or not) of Nazi plunder. We’ve covered topics ranging from patronage and collecting, to the role of the artist, the art critic, and the curator in the market. I also started a blog to share with the class shorter articles and videos collectively sourced (a favorite recent link to the Guardian article on Frieze this week has Jerry Saltz stirring things up in the comments section). Today, after listening to Harvey I asked the class what alternative models they could think of for an art market. The art market is, after all, both a mirror of and a cog in larger capitalist systems. After learning about it historically, and its operations in the last five years in particular, what regulations would they impose? If they had the utopian chance of a clean slate, what did they imagine the ideal art market to be? Alternative art schools where validation doesn’t hinge on being picked up by a Saatchi-svengali before graduation? Artworks that can be sold only once (obliterating the secondary market)? Artworks that can never travel (bye bye biennials and globe-trotting art stars!)? They’re working on answers for next week’s class.

Our recurring themes for this course have been many: the role of text in the hype-machine of the art market (from Petrarch’s mumblings in his will on the worth of Giotto’s work, to Gersaint’s catalogues extolling the virtues of a dead Watteau, and Vollard’s “support” of Cezanne); the faint presence of ethics in the art market; and the non-existence of market regulation. My students are of the generation that expect the hyperealization of consumer culture, instantaneous media, and visual information shared globally across most physical and invisible boundaries, including class and income level (cell phones have become ubiquitous, news instant). Like Facebook and Twitter, the art market is but one more social network – just one with a hefty admission fee (in a literal wallet-walloping way, and in the sense that it seems one has to part completely with one’s moral compass to really get involved in it).

We’ve gone on field trips: to meet Noah Horowitz, the new Managing Director at the Armory Art Fair. The students prepped an awesome list of questions before they met him – including taking him to task on the Armory’s parent organization, a huge merchandising, trade show, and real estate company (he was a consummate diplomat in his answers, but my students pressed the conversation later in class). We went to see a fantastic Chelsea gallery director (yes, they exist), the UBS corporate collection (smaller than we thought in the flesh, but 35,000 pieces worldwide), and for our final trip, Sotheby’s – which is where I started my lesson this afternoon.

Last lesson, we looked at the auction house duopoly of Christie’s and Sotheby’s, and discussed appraising, selling, and buying art in the auction house marketplace before taking a field trip to Sotheby’s headquarters where we were generously hosted and my students got to see behind the scenes. Today, appropriately for May 1, we filled in the gaps the tour hadn’t covered, especially the ongoing standoff between Sotheby’s and their art handlers (which eflux sent a timely update on just before my class began). I showed the class the video above of Mayor Bloomberg’s domestic partner, Diana Taylor, icily dismissing the workers’ calls for negotiation and there was a collective gasp in the room. How could someone entrusted to make sure NYC parks are accessible to all New Yorkers (she’s on the board of the Hudson River Park Trust) also summarily dismiss said hard working New Yorkers, and their healthcare, and that of their families, without batting an eyelid (Taylor does double-duty – she’s on the board at Sotheby’s too)? Turns out, pretty easily. Students at Dartmouth felt as repulsed as mine by her casual dismissal of the workers that had sweated to support Sotheby’s profits – and her seat on the board. It’s time to tell the Hudson River Park Trust (and the many other organizations she leads) that someone so out of touch with the struggles of ordinary, working New Yorkers probably shouldn’t be on the board of directors of a city-state public trust tasked with making public green space accessible to…..ordinary working New Yorkers. Though, when the art handlers lose their homes and their healthcare, at least they’ll have somewhere nice and grassy to go sleep rough, right Diana?

Keeping it in the family: Diana Taylor's other half cutting the ribbon for Hudson River Park’s Chelsea North section in 2006.

As the end of the semester draws to a close, I think both myself and the class have been left with more questions than conclusions about the nature of the art market – its ubiquitous connection to contemporary art, and historically, the seeming inseparability of art production, criticism, and engagement from the market itself. What I hope the students leave with is a heightened awareness of and critical attitude toward this landscape. I know I have – and more than that, just a deep appreciation that I’m approaching the subject from this angle, in the company of forty brilliant students, as a teacher, and a learner. My complicity as an art historian? Still coming to terms with that…..

Happy May.

Pingback: Press coverage of the Free University « Occupy CUNY – News