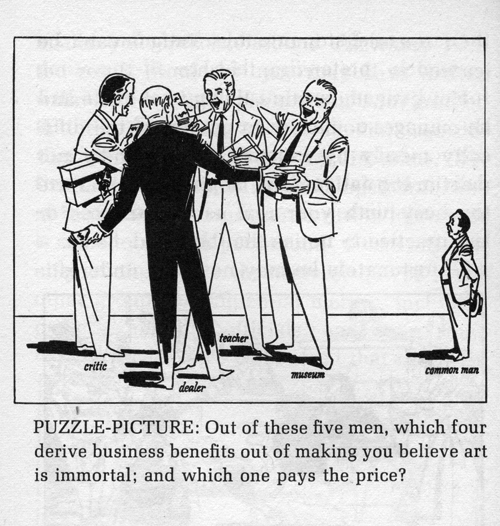

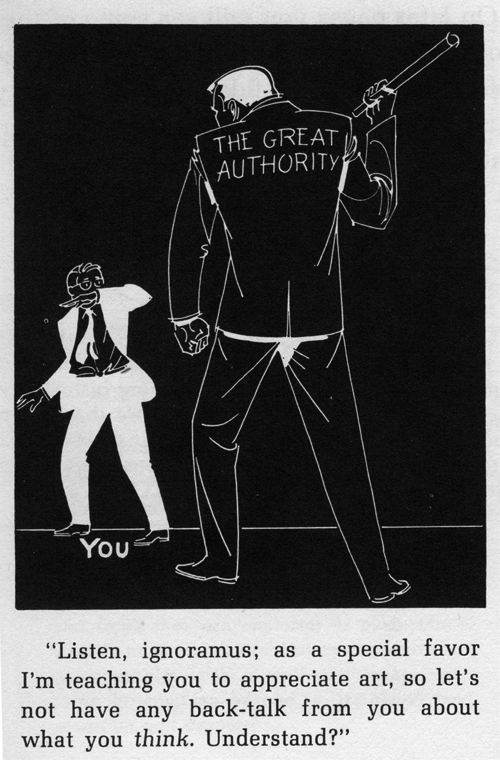

A cartoon from "Don't Get Taught Art This Way! As So Many People Do" by Theodore L. Shaw, Stuart Publications, 1967.

Not so long ago, the L.A. art world seemed split in a rift of Beatles vs. Stones proportions. This time around, it was Rainer vs. Abramovic. People who read art blogs are probably familiar with the conflict: In her letter to MOCA president Jeffrey Deitch, Yvonne Rainer called Marina Abramovic onto the carpet for requiring performers to lie nude beneath skeletons for hours at a time for the benefit of “frolicking donors.” According to Rainer, with the performers paid at “sub-minimal wages,” the fundraiser “verges on economic exploitation and criminality.” After attending a rehearsal at the invitation of Jeffrey Deitch, Rainer released a revised letter to reflect her own observations and to address some of the criticism sent her way from the event’s pro-Abramovic performers: “Their cheerful voluntarism says something about the pervasive desperation and cynicism of the art world such that young people must become abject table ornaments and clichéd living symbols of mortality in order to assume a novitiate role in the temple of art.”

It seems both ironic and fitting that Los Angeles, with its history of Aimee Semple McPherson, Charles Manson, and L. Ron Hubbard, would be the site where Abramovic got bullshit called on her for using a shamanic priestess persona to exploit the labor of idealistic young people. Maybe if the guests consisted solely of obscure continental millionaires and not, say, Pamela Anderson, the line between confrontational critique and the exploitation of lithe bodies would seem more clearly delineated?

At the time, I was squarely pro-Rainer, but unfortunately I felt the initial labor dispute angle was muddied by an insistence on involving questions of artistic merit, so that it became a question not of Exploitation vs. Compensation, but Entertainment vs. Authenticity. More Beatles vs. Stones …to which I must respond “I don’t know, does anyone want to listen to Led Zeppelin?”

AND YET, the questions the debate bring up are important: Could it be that some of the sacrifices we artists and performers make in order to be part of the contemporary art world are not actually worth it? Could it be that some of our heroes, some of the living legends, some of the pillars of the contemporary art world, are capable of missteps and doing stuff that’s dumb or even wrong??

What would Theodore L. Shaw say about all this?

Theodore L. Shaw is an obscure writer who published a series of books in the ’50’s and ’60’s with titles like Precious Rubbish and Don’t Get Taught Art This Way! As So Many People Do. I think it’s this guy’s time to shine. Shaw was singing the gospel of level-playing-field relativism about 20 years before post-modernism legitimized the practice.

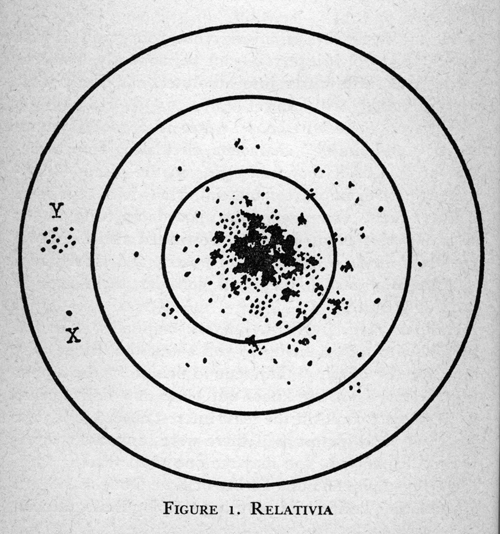

Shaw filled multiple volumes with diagrams, gag cartoons, and barbed, contemptuous prose, all seething with resentment at the Art Establishment and the mechanisms by which we are taught to appreciate “art” as opposed to “entertainment.” Shaw attempted to objectively prove that every kind of expression had its appropriate value, and that, though certain works were “more complex” than others, none were necessarily better than any others for it. He sought to prove this through a series of dubious diagrams involving concentric circles and dots, applying pseudo-scientific reasoning to what is essentially a class-based argument against snobbism posing as expertise.

In contrast to the dictum that “Art is Immortal” and that institutions and “experts” (blech!) are here to tell us what is art and what isn’t (and therefore what will endure thousands of years after we’re dead) Shaw proposes that the true valuation of art should be based on an objective grid of complexity as related to its “tiring rate” (in other words, how quickly you get bored of it). If your artwork is technically complicated and is still able to avert fatigue in your viewer, it’s really good. If it’s not all that technically complicated, but it also does not induce fatigue, it’s good enough. If it’s technically complex and induces fatigue, it is not good and if it’s technically simple and induces fatigue it is really bad. I don’t know if all this the best criteria on which to judge works of art, but I can’t help thinking that if Mr. Shaw were around today, he would have had a sweet career developing Visual Arts Content Standards for the California Department of Education.

"Into the map I have charted every art work in the world, each one being represented by a dot. They are allocated --not by 'merit,' of course--but by their degree of complexity... their distance from the centre of the map being expressive of their relative complexities." -Theodore L. Shaw, "Precious Rubbish," p. 9, Stuart Art Gallery Inc., Boston, MA. 1956.

As foolhardy and misguided as this sort of mapping might seem, I think it does hold some value for artists today. It represents a response to the dogma of its time, and was prescient of the conceptual and postmodern artists’ attempts to drain some of the more self-indulgent rhetoric of modernism by introducing the signifiers of scientific objectivity. Shaw’s gag cartoons are also step-cousins to the editorial cartoons of painter Ad Reinhardt, which alternately eviscerated the dominant art movements of the time, and taught readers how to correctly look at paintings.

Above all, the value of Shaw is not in what established movements he may have anticipated or inspired. Rather, it is the fact that he was a voice of dissent. Perhaps he was not always right or necessarily coherent, but he certainly put himself out there, and created a voice of opposition to what he felt was an oppressive and hypocritical oligarchy of critics and art institutions. The American Art World Landscape is much different today than it was in the 1950’s, but there is much that needs to be reconsidered in what we value and how we value it. Organizations like W.A.G.E. and the painfully hilarious drawings of William Powhida are presently calling into question the received wisdom of the current art economy, and what they articulate are the frustrations of untold numbers of silent art world citizens.

If we seek insight into the present moment from the past, I suspect we will find other figures like Shaw. Figures relegated to the dustbin of history, who need to be resuscitated and re-examined for a new generation of artists and art workers who might not want to take their plight lying down, naked, on a table, with Pamela Andersen staring at them.