Hirsch E.P. Rothko begins in the shitter. The opening scene of the fictional memoir, written in part by New York based artist Christopher K. Ho, introduces the eponymous protagonist: Rothko is a contemplative – albeit embittered – conceptual artist, who has become transfixed by a lewd sight on an otherwise pristine wall. Inside a swanky New York City restaurant bathroom an elaborate spattering of human fecal matter proves surprisingly ripe for thought. As Rothko stews, the scatological becomes a catalyst, prompting Rothko’s escape from the Manhattan art scene.

A series of near catastrophes follow: he gets canned from his teaching position at the Rhode Island School of Design and then he crashes his car. Worse yet for this die-hard Manhattanite, the intellectual finds himself communing with Colorado hippies on their home turf. His personal retreat into the mythology of the American West counterbalances Rothko’s professional frustrations. Back on the East coast, art had shriveled to insignificance for him; however, the expansive Colorado landscape awakens the sublime. By the end of the book Rothko has alighted from his metaphysical quest, perhaps having never embarked.

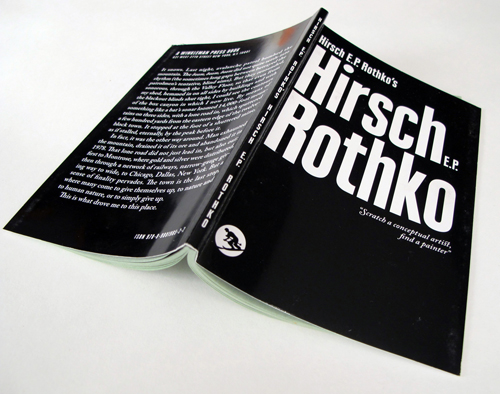

Hirsch E.P. Rothko describes one disenchanted artist’s dip into delusion. Furthermore, the text buttressed a body of work that Ho created for his 2010 exhibition at Winkleman Gallery called Regional Painting. Together the book and the paintings occasion a dialogue on the complications of a career in the arts. The sum of these parts also presents an innovative model for art criticism from one unique perspective of an artist.

All artists are critics but not all critics are vocal. Rothko provides a distinct voice for Ho’s criticism on the contemporary art world. The two are different entities yet Christopher K. Ho is Hirsch E. P. Rothko; the name of the main character is an anagram of the author’s name. They are composed of the same elements but these pieces have been rearranged and reconstituted. One is fact and the other, fiction.

The plot of Hirsch E.P. Rothko is an anagram of sorts, too. Based in part on actual events, this fantastical tale interlaces real and imagined events within a critical discourse. The novel blurs the line between fact and fiction, commentary and concoction. Equal parts artist and critic, Ho believes that “Fiction… is the necessary antidote to an apolitical, personal practice—one that prevents that practice from being merely disengaged.” Fiction is malleable, organic and therefore, endlessly productive. In the same vein criticism should lead to a fluid conversation. Thus, fiction is the most potent form of criticism. As Rothko/Ho contends, creative criticism via the fanciful will suspend indifference. Art criticism can be artful.

The following interview with Christopher K. Ho took place in April 2012.

JAG: I’d like to begin by talking about your education and training as an artist and critic. The trajectory that you’ve taken is unconventional. Can you narrate your educational history?

CKH: Like many artists, I eyed a career in the arts long before college. The question was if art making would be financially viable and culturally acceptable. At 18, I hedged, and entered Cornell’s five-year architecture program. In retrospect, the choice was good, even if it seemed a compromise at the time. Art historically, I exited school just as site specificity peaked, and my architecture background positioned me perfectly to address that practice’s concerns. Art theoretically, the ‘90s witnessed substantial overlap between the discourses of art and architecture. Artists read Anthony Vidler on the uncanny and Kenneth Frampton on regionalism, and architects followed Hal Foster on trauma and Rosalind Krauss on the informe. Sadly, this overlap has since dissipated. Issues of production and sustainability now preoccupy architecture, while the art market continues to dominate the art world.

JAG: After Cornell you ended up at Columbia’s PhD program for art history. Why did you seek the MA/M. Phil. at Columbia over a Master’s of Fine Arts degree elsewhere?

CHK: By my fifth year at Cornell, architecture studio interested me less than seminars led by vibrant teachers including Foster and Vidler, as well as Christian Otto and Mieke Bal (the last a fellow at Cornell’s incredible Society for the Humanities). When applying to graduate school, PhD programs in art history made sense. I entered Columbia in Fall 1997. It provided a foothold in an inhospitable New York; the school’s location was its first advantage.

Equally advantageous was Columbia’s top-notch faculty. In lecture, Krauss riveted. Her seminars were purposeful and urgent. The way she identified and isolated a problem, worked through it, and moved on to the next amazed. The index, pastiche, and, lately, the post-medium condition are but a few examples. If Benjamin Buchloh—then also at Columbia—is akin to the slightly dogmatic, always consistent committed painter (an analogy ironic given his ambivalence toward the medium and one that he would surely protest), Krauss would be the site-specific artist who peregrinates from bracketed problem to bracketed problem, each foregrounded by immediate and evolving circumstances, and the sum of which remains unknown.

It would be Krauss’ approach that provided the model for my own nascent trajectory. Through whatever means at my disposal—art making, criticism, curating—I attempted to address what I saw as salient, successive problems in contemporary art: the monochrome, independent curating, regionalism, narrative, and, most recently, the aesthetics of decency.

JAG: How have your studies fomented your interest in art criticism?

CKH: I concluded my time at Columbia at the M. Phil stage, never finishing (or even really beginning) my dissertation, which would have been on Gonzales-Torres. Studio, curatorial projects, and writing criticism increasingly took up time. Initially, the last provided an outlet for ideas and a breather to graduate school’s longer research papers. Monthly deadlines and a 500-word limits encouraged exploring multiple avenues. Criticism also constituted a portal to contemporary art, which at that stage remained distant—something I read about in magazines rather than lived.

In 2002, Omar Lopez-Chahoud (with whom I and Regine Basha co-curated the Brewster Project the year before) introduced me to Ros Furness at Modern Painters. This became my first regular writing gig. Suddenly, I was forced to see shows weekly, engage intellectually with them, and to pinpoint kernels for potential reviews. My repertoire of young artists expanded exponentially. (At Columbia even Gonzalez-Torres, who died in 1996 and already had a Guggenheim retrospective, pushed limits; classmates stuck with Picabia or Rauschenberg.) Soon I approached shows with reviewing them in mind even if a review wasn’t in the works—a useful and challenging habit that persists today.

JAG: After Columbia, you’ve been active as a professional artist and within academia. You curate, create and critique work. How do you define these different roles?

CKH: In the popular imagination, curating holds the most secular power, followed by criticism, while art making is potentially the most exalted. For me, they are equal and allied. Indeed, my interest in and definition of curating—specifically independent curating—emerged from a distinctly art-historical problem: What logically follows institutional critique’s shift from work to frame? Curating presented a viable response; more, independent curating provided a contemporaneous, critical option to institutional critique’s devolution into installation art in the ‘90s.

My first curatorial project was a hybrid. I was moving apartments within two blocks. During the leases’ two-week overlap, artist Cletus Dalglish-Schommer and I invited eleven artists—including Rory Donaldson, Kira Lynn Harris, Nina Katchadourian, Julia Meltzer, Andrea Ray, Peter Rostovsky, and Kerry Tribe—to intervene in either or both spaces. Each could select and incorporate furniture and personal effects. The opening started at the old space and progressed to the new, with a two-hour overlap. Unpacking (1999) established the tone for subsequent hybrid art-curatorial endeavors. A personal favorite of these is Microviews (2002), a collaboration with Stephan Apicella-Hitchcock. It collated images taken by artists from the Lower Manhattan Culture Center’s residency in the World Trade Center prior to 9/11. Thousands of images were individually filed by formal characteristics and cross referenced in a row of upturned file cabinets through which viewers rifled.

JAG: Can you comment on the current state of art criticism and theory in academia based on your experiences teaching at graduate institutions like RISD and Cranbrook?

CKH: Intuitively, studio art generates art history. In fact, the latter is an autonomous discipline with its own canonical history and methods, and may have little or nothing to do with production, especially of the contemporary sort. At Columbia in the ‘90s, the MFA and PhD programs stood at opposite ends of campus, equally prominent and utterly independent. Conversely, an art student may find art history useful but unnecessary. At RISD, I taught contemporary art history from 2000-08. To my surprise, some of my best students made the worst studio art, and vice versa.

In contrast, criticism—distinct from art history or theory—shares genetic code with studio critique. Both entail quick thinking; non-linear discussions for which the endpoint remains unclear; a cacophony of simultaneously competing, complementary, and augmentative theses; and the real risk, even irrational championing, of irresolution. Both reward the adventuresome, and strive to be discursive and productive, not didactic and retrospective. Elliott Earls’ 2D studio at Cranbrook is predicated on this shared DNA. Students arrive at crits having written short reviews of other students’ works, which they read aloud to initiate discussion.

Theory is the trickiest. My generation seems the last for which it meant something. Today, theory of the French/Frankfurt type is endlessly parodied and, to be sure, often collapses under its self-importance, especially in its fourth or fifth iteration. Which is not to say that it isn’t or can’t be constructive and informative in the studio—it certainly was from the ‘60s through the ‘90s—but that it may not be imperative or urgent. For the most part, school curricula reflect this.

JAG: As a young artist I can feel timid about being critical, especially about the work of my peers. Do you have any pointers for developing a critical voice?

CHK: As a result of our discursively biased (rather than technically oriented) BFA and MFA programs, artists rarely believe their work possesses a single, correct meaning. I find that most appreciate a critic’s or fellow artist’s engagement and interpretation, regardless of whether that interpretation is the intended or wished for one. Also, artists should keep in mind that they can—and should—talk back. Magazines and newspapers welcome letters from readers, and comment boxes nearly always follow blog posts. (The “Letters to the Editor” section has hosted some of the richest dialogues in contemporary art—think, for instance, of Liam Gillick’s riposte to Claire Bishop’s mis/reading of his work in October.) The more frequently artists respond, the less hesitation others—like yourself—will feel, since any criticism will initiate dialogue rather than constitute a final word.

JAG: Lastly, which art critics have been influential to you? Which artists who write or engage in some form of criticism do you respect?

CKH: Jonathan T.D. Neil possesses the requisite historical-theoretical background combined with immense drive to articulate and explore new models and emergent criteria; he operates alongside, not against or after, artists. On the older end, Thierry de Duve, more an art historian proper than a critic, remains punkish despite his many institutional affiliations. Seth Price, like Thomas Lawson, is associated with one signal essay. Dike Blair and Roger White inherited Peter Halley’s mantle; all write/teach/edit as well as paint. Gregory Sholette’s observations are as keen as his activist art is committed. Jose Ruiz curates, and is one of New York’s most underrated artists.

Hirsch E.P. Rothko can be purchased at Publication Studio in Portland, Oregon.