"United States: Most Wanted Painting" by Komar and Melamid.

An alarming number of Americans are taken by the notion that all past and present leaders of their Executive Branch converge and coexist in a state of simultaneity on a mysterious plane of existence decorated in the neo-classical style. I kind of believe it too. I call it The Hall of Presidents Syndrome.

The Hall of Presidents is a feature of Disneyworld wherein animatronic approximations of all 44 American Presidents are presented to an audience in a kind of civic religious ceremony. Within the Hall of Presidents, matters of grave importance are perpetually being discussed, historic speeches both eloquent and pithy are continually paraphrased, and the Union is forever validated and supported. The physical presence of these Presidential avatars tricks the minds of Americans into thinking that these men would be able to get along reasonably, and that the Americas they inhabited in their various lifetimes are all reconcilable, according to the linear march of Progress and each man’s unstinting devotion to The American Dream.

"The Forgotten Man" by Jon McNaughton, 2010. Limited edition print. Via https://www.mcnaughtonart.com/.

It is this fantasy that is reinforced, then threatened, in The Forgotten Man, a painting by Utah artist Jon McNaughton, which has become an internet sensation due to its guileless, ham-fisted, yet somehow opaque use of history painting conventions in the service of a doctrinaire Christian conservative value system. In The Forgotten Man, current President Barack Obama, who gets along with everyone just fine in the actual Hall of Presidents, is carelessly stepping on the Constitution as he looks glumly to his left. James Madison looks on in horror and makes a very George-Costanza-like show of his dismay. Behind Obama stand a bunch of Democrats (like Clinton and FDR) who applaud for some vague reason (’cause they’re all looking at a future of big government socialism or something?). Either way, what McNaughton employs his own 2-D Obamavatar to do in his next painting would surely get the 44th President kicked out of the club for good.

"One Nation Under Socialism" by Jon McNaughton. Via https://www.mcnaughtonart.com/.

No longer content to step on the Constitution, Obama is now burning it!

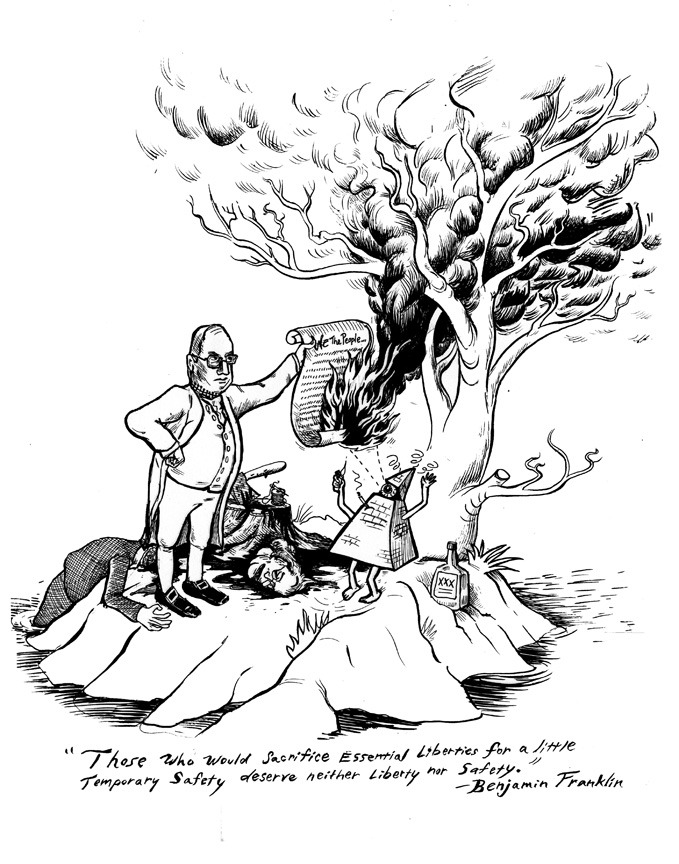

I will make no bones about it: I enjoy the work of Jon McNaughton. Certainly not for any of the reasons McNaughton would intend, but I reserve an appreciation for this work that I insist is not ironic. As someone who once designed a t-shirt wherein Dick Cheney has cut off the head of Benjamin Franklin, switched bodies with Franklin’s corpse and is burning the constitution with the help of a dancing Masonic Pyramid on a desert island, I understand the appeal of such imagery.

"Franklinstein" by John P. Hogan, 2002.

Constitution burning is an irresistible image of protest no matter what side of the aisle you’re on. Setting things on fire in general always makes an impression.

Ed Ruscha. "Los Angeles County Museum on Fire," 1968. Oil on canvas. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., Gift of Joseph H. Hirshhorn, 1972. © Ed Ruscha.

And before we throw McNaughton under the bus for making short-sighted, heavy-handed works with an overly specific political agenda, let us not forget the gradual institutional legitmization of people that do stuff like this:

Shepard Fairey. "Obey Bush One Hell Of A Leader," 2004. Silkscreen print.

McNaughton’s success is unsettling to some for good reason. Los Angeles Times art critic Christopher Knight actually takes the time to designate McNaughton as junk not because art world insiders take it seriously, but because the American art world itself is fighting for its life. According to Knight, McNaughton represents a close-minded, opportunistic solution to the problem of ever-dwindling government funds for the arts. A painter attacking big government is yet another blow, this time from the inside. McNaughton’s modus operandi, an aggressive variant on the Thomas Kincade model, is to create relatively cheap, didactic work that speaks to people’s prejudices. It’s a freemarket approach and it bums out people with advanced degrees, but between McNaughton and Fairey it’s obvious both sides of the political spectrum are guilty of this cynicism.

Just like the sneering Democrats in The Forgotten Man, the figure of McNaughton represents a host of bad things to people in the art world. On the other hand, we’d be foolish not to recognize an opportunity to re-examine history painting when we see it.

History painting is currently a reviled genre, and only the most fearless painters of cultural shame and embarrassment have been willing to sail its waters. Painters like Peter Saul and Sean Landers each took their own stab at the genre. Saul’s painting Columbus Discovers America, for example, embraces and amplifies the racially-charged imagery and imperialist agenda of our historical narratives.

Peter Saul. "Columbus Discovers America," 1992-95. Acrylic and oil on canvas. 96 x 120 inches (243.8 x 304.8 cm).

Sean Landers’ 18th century figures with breasts for faces associate our Colonial forebears with both a repressed Puritan shame and a Freudian need to be coddled. L.A.’s Ben White conflates figures from American history and folk tales with contemporary box stores and roadside attractions, pointing to the relativity of cultural import and the collapsible nature of intellectual, philosophical and religious “progress” in America. These artists have been serving reminders of the dysfunction that underlies our sense of national identity.

Ben White. "Thomas Jefferson Sets Himself on Fire in the Parking Lot of the Blockbuster Video Near The Creation Museum," 2010. Acrylic and spray paint on panel. Courtesy Blythe Projects, Culver City, CA.

McNaughton accepts the White Christian Patriarchy’s version of history at face value, without criticism. This is how he can repeatedly use white males to stand in for “everyone” while remaining sincerely oblivious to the racial prejudice this decision engenders. His work is such a blatant appeal to American middlebrow tastes that it unwittingly evokes Komar and Melamid’s United States: Most Wanted Painting [pictured at the top of this post]. Yet those of us who “know better” should not get too smug about it. These images are controversial because they really do mean something to us. The Founding Fathers have been raised to a mythical status, and even our present President has his own iconography. We do not have to venerate these symbols, but we would be foolish not to engage with them.