“All my gestures, movements, activities, creations were this life, original or essential in itself. It was at this time that I used to say that “painting for me is more than a function of the eye. My works are but the ashes of my art”.” — Yves Klein, from Truth Becomes Reality

In the early postwar period, artists in Europe, the US and Japan faced a philosophical crisis: in the wake of destruction on a scale previously unimaginable, confronting the political and social fallout of World War II, many of them felt that artistic practice, as it had existed prior to the war, had lost its relevance to the human condition. As the Gutai Group leader Yoshihara Jirō wrote in the 1956 Gutai Manifesto, “To today’s consciousness, the art of the past, which on the whole displays an alluring appearance, seems fraudulent.” There seemed to be a need for a more authentic artistic experience that could at least compete with, or possibly even help process, the traumatic realities of the war and its aftermath. This search for authenticity provoked a shift toward art that sought to forge connections to the everyday, whether through materials, subject matter, process, or conceptual orientation. Part of this shift was the development of performative strategies and eventually, performance art. As Kristine Stiles writes in “Uncorrupted Joy: Forty Years of International Art Actions, Commissures of Relation:”

“Removing art from purely formalist concerns and the commodifications of objects, artists employing action sought to reengage both themselves and spectators in an active experience by reconnecting art (as behaviour) to the behavior of viewers. Art Actions and their related objects move through the body of the artist in his/her material circumstances to the viewer in the social world…a situation in which the object draws viewers back to actions completing the cycle of relation between acting subjects, objects, and viewing subjects.”

The most direct way of drawing attention to this contingency of the art object on social relations–in other words, of reconnecting it to life–was to transfer the contingent moment of the art object–the action of artmaking–into a public, shared experience. This strategy could reveal the simultaneously exhilarating and mundane nature of the creative act, both enlivening the experience of the artwork to the audience while also breaking apart the privileged experience of the creative act, usually hidden away in the studio, to make it accessible to a broader public.

Given my interest in Asian and especially Japanese art, the immediate example that I look to for this transition is the Gutai, a group based in western Japan and active from 1954-1972. Their name has been translated by terms ranging from “concrete” to “embodiment,” but generally evokes a shift away from representation and toward manifestation. Their artwork took many forms, including objects, environments, performances, paintings and films, and often lived in the interstitial spaces between genres. A constant drive to, in the words of Yoshihara’s favorite exhortation, “create what has never been done before,” was what tied these experiments together. This pushed the group towards experiments in interactivity and performance that played up the relationality of the artwork. In works like Kazuo Shiraga’s Challenging Mud (1955), exhibited outside of Ohara Kaikan in Tokyo for the 1st Gutai Art Exhibition, or Please Come In (1955), shown in Ashiya Park as part of the Experimental Outdoor Exhibition of Modern Art to Challenge the Midsummer Sun, the act of creation is theatricalized and placed within the exhibition space, however unconventional that space may be. For Challenging Mud, Shiraga, dressed only shorts, grappled bodily with a field of mud, cement, and plaster during the exhibition opening, then left the remaining composition–something between painting and sculpture–on display for the duration of the exhibition.

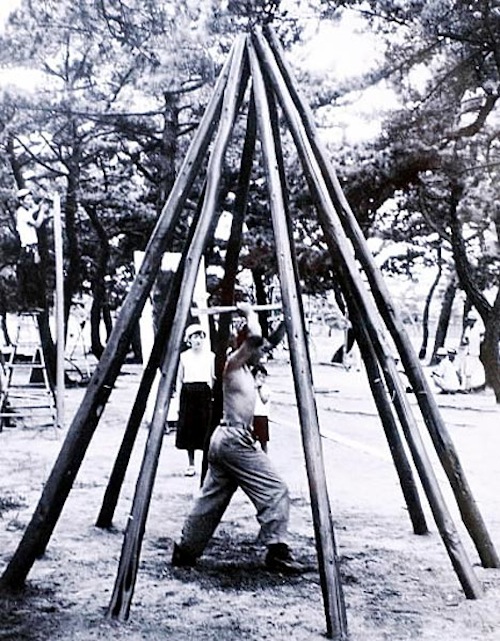

Similarly, with Please Come In Shiraga stood eleven logs on end, painted red and arranged conically. Standing inside this construction, he swung an axe around to leave cut marks across the inner surfaces of the logs. The resulting cuts stood as both the trace of the act and, in combination with the logs and the sky, a composition visible to the viewer who entered the structure. Both of these works stress the importance of the act of making as an integral part of what constitutes the work of art, but the latter especially plays up the relational nature of the artwork: the piece can only be experienced in its entirety when the visitor enters the artwork, forcing them to deal physically and consciously with the act of viewing, while simultaneously positioning themselves as a part of the work for any other visitors viewing that work from afar.

Shiraga Kazuo. "Please Come In," 1955. Performance from the The Exhibition of Modern Art to Challenge the Midsummer Sun, Ashiya Park, Ashiya, Japan.

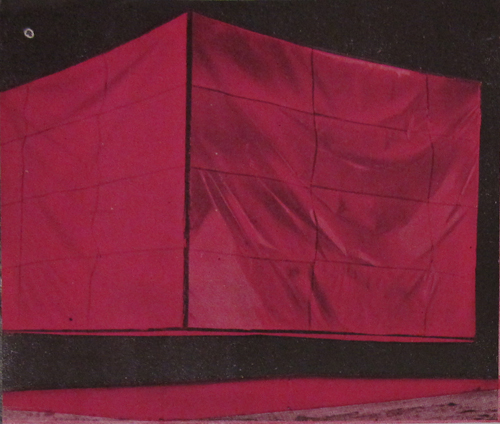

Shiraga was by no means the only Gutai artist to create works that brought this contingency to the fore. Simply looking at the outdoor exhibitions, works like Yamazaki Tsuruko’s Work (Red Cube) (1956), Shimamoto Shōzō’s Please Walk on Here (1956), and Yoshihara Jirō’s Please Draw Freely (1956) were all works that required the participation of viewers in order to complete their intended experiences. Work (Red Cube) was a red vinyl fabric cube that would be lit from inside to function as a ground against which visitors could play with the effects of their shadows. Please Walk on Here was a series of boards of differing stability that covered the surface of long wooden boxes. Visitors were invited to traverse these boards, thereby making visible, through bodily movement, their material qualities. Please Draw Freely was a 7 x 15 foot wooden board that visitors were invited to graffiti with paint and markers, blurring lines between author and viewer. In each of these cases the visitor was co-opted into the artwork itself, making their complicity in the viewer-object relationship both active and ambiguous. This ambiguity made visible the relational aspect of the work of art, drawing it into a social space that positioned it as a dynamic point of contact between artist and viewer.

Yamazaki Tsuruko. "Red," 1956. Installation view from 2nd Gutai Art Exhibition, Ashiya Park, Ashiya, Japan. Image from the journal Gutai 5.

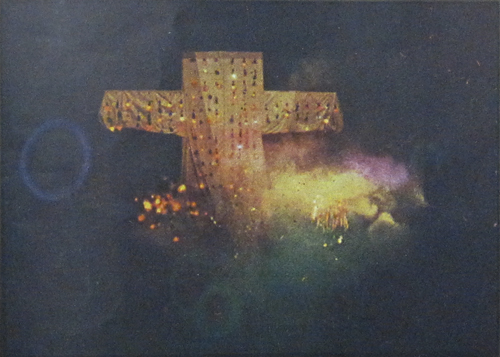

Even beyond the relational aspects of individual works, however, it should be noted that the Gutai artists played off of each others’ pieces and strategies. In spite of the diversity of their practices, aiming at the expression of individuality that Yoshihara promoted so adamantly, there is also a relationality between the Gutai artists that builds a greater whole out of the group than any one individual artist. While the links between artworks in the outdoor exhibitions may have been more about creating in a similar spirit, certain works the Gutai created for the stage directly played off of each other. During the first Gutai Art on Stage, the most direct interaction was the finale in which Tanaka Atsuko’s Electric Dresses, wearable clothing covered in blinking lights, came out accompanied by Motonaga Sadamasa’s giant smoke-ring machine, backlit with stage lights and accompanied by concrete music. Although ostensibly separate works, these pieces were presented so as to create a dialogue with each other that spoke to different aspects and phenomenological experiences of the theatrical space. The Gutai did four more similarly theatrical presentations–the 2nd Gutai Art on the Stage Exhibition in 1958, a 1962 collaboration with the Morita Dance Company, 1967’s Fourth Summer Festival in Osaka, and the Gutai Art Festival of 1970: a grand staging of their performance works for Expo ’70 in Osaka. This final performance at Expo ’70 was notable in that the works were presented in the central plaza not as a sequence of distinct individual presentations, but as a spectacle of overlapping and interacting pieces that could be imagined either as individual works or as a complex whole.

Finale from Gutai Art on the Stage, Sankei Kaikan Hall, Osaka, Japan, 1957. Image from cover of the journal Gutai 7.

This collaborative mentality was at the core of Gutai experimentation. Art historian Reiko Tomii suggests that this was a result of Yoshihara’s stern tutelage and drive to escape the limitations of his own artistic experiences:

“I think Yoshihara was very shrewd to set up situations for experimentalism. If he had not engaged the artists in these particular situations, I’m not sure they would have been as experimental on their own…Yoshihara was a great mentor in that sense, constantly encouraging a growing vocabulary of contemporary research and ideas through new material and performance.”

Building off of each others’ experiments and Yoshihara’s feedback, the Gutai artists became aware of the potential for interactivity between themselves and the art object, the art object and the viewer, and between different artworks. This network of interactions is the human side of the artwork that opens up the possibility of art entering the everyday.

Of course the Gutai were not the only artists experimenting in this direction. Yves Klein, with his declaration to “tear down the temple veil of the studio” and “keep nothing of my process hidden” similarly sought ways to enliven the artistic experience. While series like Klein’s Fire Paintings and Anthropométries explored the ability of the mark to convey the process, it was really with his performance pieces that relationality came to the fore. Take, for example, Anthropométries de l’époque bleue (1960) in which he directed nude models, to the accompaniment of a string ensemble, to cover themselves in his signature blue paint and create a composition on canvas by pressing their paint-laden bodies onto the canvas suspended on the wall. Not only did this demystify the artistic process, it actually turned it into a collaborative project in which the artist was one step removed from the artwork, instead directing his collaborators–the models–to create the composition, establishing an interdependency of the key players without which the art object could not come to be. His plans for Capture du vide, a work in which participants would be asked to return to their homes at a designated time leaving the urban space emptied of human presence, would have taken this relationality a step further, pushing the collaboration to include the spectators in a work that could only be realized with the full participation of all viewers, but could not be experienced by any.

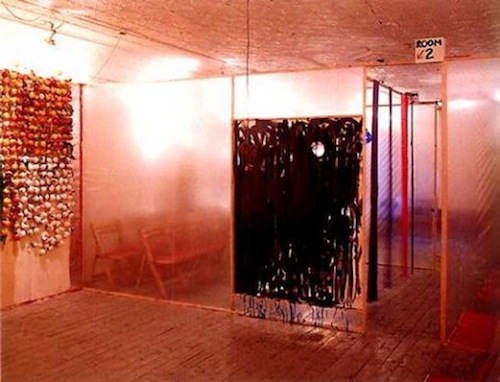

Picking up a similar strain of collaboration, Allan Kaprow’s Happenings relied on group action, minimally directed, and resulting in physical manifestations that clung to an untidy collage aesthetic. For works like 18 Happenings in 6 parts (1959), Kaprow mixed the chance processes he learned under John Cage’s tutelage with the enveloping environments that developed from his expanding collages. Providing basic instructions about where to move and how to react to certain visual and auditory clues, he had audience members navigate seating arrangements and quasi-architectural spaces delineated by semi-transparent plastic sheets painted and collaged with references to his previous works. Paul Schimmel characterized this situation as transforming the audience into props, but the reality is that this methodology relies on the active complicity of the audience to realize the desired effect, and can only be experienced from within the work. Rather than treating them as mere props, Kaprow sets up a mutual dependency in which the artwork is an all-encompassing collaborative process-environment: the substrate of the relational interaction. Through this methodology, Kaprow sought to fulfill the predictions of his 1966 Manifesto:

“Contemporary art, which tends to “think” in multimedia, intermedia, overlays, fusions and hybridizations, more closely parallels modern mental life than we have realized. Art may soon become a meaningless word. In it’s place, “communications programming” would be a more imaginitive label, attesting to our new jargon, our technological and managerial fantasies, and our pervasive electronic contact with one another.”

As becomes clear from Kaprow’s statement, this relational structure was more than simply a means of making art accessible: it sought to prove the relevancy of art to address and critique the momentum of science and technology, especially the susceptibility of these fields to co-optation by totalitarian systems of commerce and politics. Similarly, in her analysis of Yoshihara’s influences leading up to the establishment of Gutai, Ming Taimpo explains that the individual expression he sought through originality and new forms of expression was in sync with a push in Japanese post-war political theory for subjective autonomy as a solution for the problem of the feudalist mentality that had allowed the state to assume a Totalitarian structure. It is in this line of thinking that Yoshihara wrote in the first Gutai journal that “It is our deep-seated belief that creativity in a free space will truly contribute to the development of the human race.” Ultimately it seems that the drive for this relational, collaborative work was to bring back a sense of the human element to an increasingly austere world, since, as Kristine Stiles writes, “For Shiraga, Murakami, and Klein, the very corporeality of the human body defeats technological and scientific determinism.”

Pingback: Time Deprived | revel mama