The following musings are all loosely inspired by watching Mary Reid Kelley in the “History” episode in Season Six of Art in the Twenty-First Century, and thinking about how family, history and family history play into contemporary art.

Novelist John Galsworthy dedicated his Forsyte Saga — five novels, some of them upwards of 800 pages long, about a tangled and divided family–to his wife. He thanked her for encouraging, sympathizing, criticizing, and making him the writer he was. This wife of his, named Ada Nemesis, had been hard to come by. She’d been the wife of his cousin and it had taken her ten years from the time she had fallen for Galsworthy to finagle a divorce. So it’s hard not to wonder if Ada contributed more than encouragement and criticism to the drawn-out, almost-incestuous Forsyte Saga romances.

Netflix recently made the 2002 The Forsyte Saga miniseries available on demand, and nearly every friend I’ve mentioned it to admits to having watched at least part. In it, members of two sides of an estranged London family cannot help but keep falling in love with each other. First, beautiful Irene steals her cousin-by-marriage’s beau, than, before divorcing her difficult husband, ends up tangled with the same cousin-by-marriage’s father. She marries this cousin’s father, a widower whose younger child has already married another estranged cousin, and they have a baby who will grow up to fall in love with the daughter Irene’s first husband has by a second wife.

All of London at their fingertips, and those Forsytes only want each other. This seemed absurd at first, an excessive Victorian soap opera, until I remembered my own family’s darker secrets. Like the great uncle who began an affair with his neighbor’s wife. This neighbor also happened to be my uncle’s wife’s brother. So his child by his brother-in-law’s wife, whom he couldn’t marry until the death of his devoutly Catholic first wife, was the cousin-in-law to his children from his first marriage. Unconscionable family webs might actually be normal.

If Galsworthy had been in the creative writing class I took senior year of college, the instructor, an insecure 30-something playwright, would have called his family sagas “kitchen sink” dramas. He would have used the term, coined in the ‘50s to describe London painters of domestic scenes, derisively. It hasn’t been okay to just paint or write about domestic family drama for a while, unless you’re also able to step outside of the story and acknowledge we are all cultural constructs. Think of the Pop artists, the appropriationists, the Pictures Generation. Cindy Sherman, Matthew Barney. They all dealt/deal with history from a distance. But the kitchen sink stigma seems now to be fading, or at least certain interesting, young-ish artists have stopped keeping their distance.

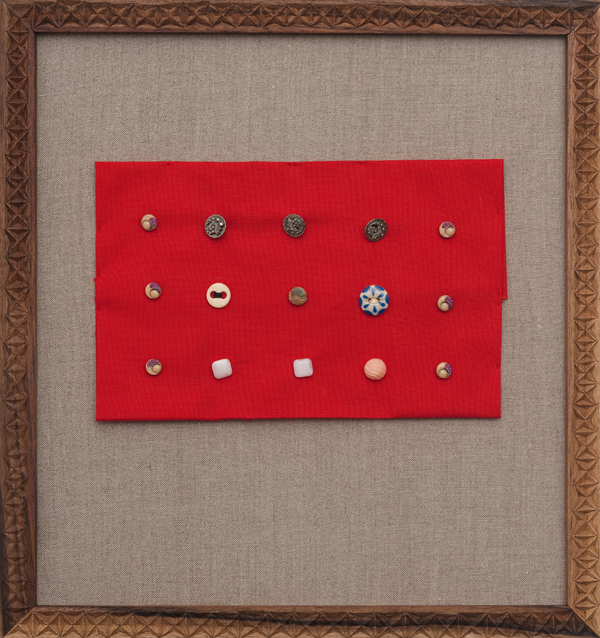

Patricia Fernandez. "From the Collection of Asun: Así se lo conté," 2011. Sewn buttons and fabric. 15 x 13 inches.

Artist Patricia Fernandez, who has work in the newly-opened Los Angeles Biennial Made in L.A. and in a current show at ltd Los Angeles, mines her history for (literal) material. The buttons on her canvases are part of a collection that began after her grandmother bestowed on her some particularly precious buttons. The wood carvings she does are based on instructions from her grandfather, a man whom, I have heard by word of mouth, initially refused to train Fernandez, because wood-carving is for men. Then he realized his is a dying craft and relented. So Fernandez’s art is about what gets passed on and what doesn’t, about what heirlooms tell us and what they hide.

Kenyatta A.C. Hinkle, also in the Made in L.A. biennial, is a writer as well as an artist. She has been working on a project that began with her brother’s name. His first name is “Sir,” so “everybody would have to address him with a title of respect, regardless of the power relations he encountered as a black man living in a turbulent racially liminal Kentuckiana.” The blog for the project, which will ultimately be a prose-poetry book, is a fascinating collapsing of family history, history of a place, and history of race and gender. It’s all tied up together.

Galsworthy said the family is a “clear reproduction of society in miniature,” and he was right, except that each family reproduces a different version of society, which is why delving into those versions seems so fruitful.

For those of you in L.A., Kenyatta Hinkle performs an ethnomusicological event at the Hammer Museum tonight called Kentrifica Is, another project that collapses personal history into much bigger histories.