Try hard and then try harder. That’s probably the best lesson I learned as an artist-curator of the 8th annual Movement Research Spring Festival. Sponsored by Movement Research, “one of the world’s leading laboratories for the investigation of dance and movement-based forms,” the festival explores contemporary dance, performance and related media through workshops, discussions, showings, installations, and discursive formats.

Cover of the festival brochure with black glitter fingernail pointing; image credit: Joey Kipp.

Charged with building a festival in New York from the ground up, my fellow artist-curators, Eleanor Hullihan, Neal Medlyn, Enrico Wey and I borrowed from the famed Salt ‘n Pepa anthem, “Push It Real Good,” as this year’s theme. Thinking of the apocalyptic predictions of the year 2012, our mission was to “push it past the limits of what we know and challenge our bodies and minds to test the boundaries of form and action.” In our observation that “performance is happening everywhere” in the 21st Century, burning questions arose:

“What is the measurement of discipline and energy that is necessary for our work?”

“How do we measure value in the midst of economic ruin?”

The Mayan calendar and the end of the world. Image credit: vcstar.com.

Moving forward with these questions, we came to The Center at West Park (West Park Presbyterian Church) to set up an immersive festival environment during the period of May 31-June 3. West Park has built a reputation for its support of art and activism for well over a century. Supporting the recent wave of Occupy Wall Street protesters, it has been at the forefront of the civil rights, anti-Vietnam War, and anti-nuclear arms movements of the 1960s. The church also championed homosexual clergy inclusion and same-sex marriage rights, among other activities. With this DIY spirit, we installed a PA and lighting equipment for performances in an upstairs gymnasium, and a number of installations in its six or some odd rooms. And we scoured and dusted and swept and attacked that fierce beast of a building like a bunch of art pirates cleaning ship.

Where it all happened: The Center at West Park. Image credit: architecturalappetite.blogspot.com.

I am not going to pretend to be okay. Even now, each night I dream of being at West Park, looking for something or someone, and climbing labrynthine staircases that lead to more staircases and more staircases…and I cry out for a fellow curator who is somewhere, in another room, searching for an exit. But in my post-festival imagination, a different kind of entrapment has also emerged. It’s my memory stuck on events that affected me far beyond the moment of the experience: the excitement, willingness, and investment of artists to push themselves fostered an environment where a sense of permission, experimentation, and discovery thrived.

Here are a few highlights from Push It. Real. Good. (Just a few, not an all-inclusive list!).

Performer Bridget Everett giving a sermon-lap dance. Image credit: Christy Pessagno (after the style of Dona Ann McAdams).

May 29: Bridget Everett is known for her performances with her band, The Tender Moments. Commonly shown in bars, clubs and theaters, Everett and her band came to the sanctuary of West Park for the finale of our opening night performances. Everett was ever the minister in our church of postmodern anarchy, where she sermonized, sang songs, and climbed on audience members. One could easily characterize Everett as an entertainer, but this would belie the fact that what she is ranting and singing about is tough stuff: family alcoholism and neglect, latent homosexuality, breast cancer, and body-image “issues,” i.e., the fabric of our lives. It wasn’t easy to listen to her stories, and laughing did, indeed, feel like sin. The laughing was mixed with pain, the pain of what she said, and the humor of how she said it. There was a moment when she brought Eleanor’s husband onto the altar to conduct a “sacrifice” of sorts, pouring candlewax onto his legs and enforcing an impossible airplane position. This was a moment when I thought show had maybe gone too far? But that’s what the festival was for….

CA Conrad reading (Soma)tic Poetry. Image credit: everseradio.com.

May 30: Philadelphia-based poet, CA Conrad visited the festival to teach a workshop and participate in the evening’s poetry event, “Body Language.” As we assembled on the west side of Central Park, Conrad laid out his plans, which had to do with touching nature, forming a “rope of blood” with each other’s pulses, and chanting lines from the notes we generated in each exercise. In the midst of the constant stress and frenzy of city life, the simple instructions of touching a rock or leaf seemed a tall order. I had to step out a couple times to attend to curatorial duties, regretfully withdrawing from the group to touch my smartphone. But by the time we formed the “rope of blood,” I was all in. Two groups of participants formed circles where each of us was to feel the pulse of another with our fingertips. I do not know how long we held one another’s pulses, but it was long enough for me to understand the name of the exercise. It was as if I was a part of the people in my circle, forming one continuous “rope,” without end. When we released one another and sat to write, the entire park seemed to radiate. Here’s a sample from my notes:

wild synapses firing

shapes unfold from ruin;

immaculate desperation of

not being everything cuts

the atmosphere but

the promise of return beckons

sweet thickness, abandon

void

…

Arturo Vidich and Aki Sasamoto perform Yvonne Meier's Scores. Image credit: Christy Pessagno.

That evening, Conrad blew everyone’s minds at the poetry reading (stay tuned for a video excerpt in a future post). Choreographer Yvonne Meier read her movement scores, or Scores (as she calls them) like poetry, and later performed them with Aki Sasamoto and Arturo Vidich. Perhaps because Meier reads her Scores as a performative act, she is used to the articulation necessary for reading poetry. For a first experiment, it was exceptional, generating imagery, alluding to gesture and behavior in parts both Surrealist and the New York School.

Savannah Knoop's exacting solo to C & C Music Factory's"Everybody Dance Now." Image credit: Christy Pessagno.

May 31: This was the day when my fellow curators and I really felt the blow of going non-stop for weeks on end, after the adrenaline-rush of the launch and success of the events. After cleaning and repair, we settled down for a concert of improvised music in the sanctuary, turned down the lights and listened. So transported was I by the duo of guitarists Jesske Hume and Ryan Ferreira that, probably by the time solo percussionist Tatsuya Nakatani played, I had begun to levitate. Mike Pride and Mick Barr came together at the end of the evening and performed what they called a “cleansing set.” Upstairs, in the gym were the makings of “Mixed Tape,” a performance experiment with pop songs, six or some odd dancers, and a pinch of sabotage. This event, with its wild, all-out energy, was a real performance party with pieces popping up throughout the space.

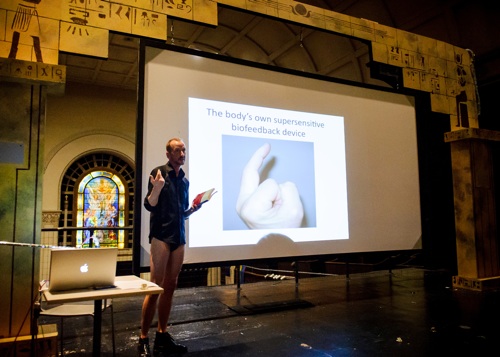

Let's Talk About Sex: John Jasperse's lecture on anal health. Image credit: Ian Douglas.

June 1: Let’s Talk About Sex. What happened here? A performance roundtable about sex: how-to’s, personal history, pillow-shredding, and massage role-play. What you see above is a power-point presentation by choreographer John Jasperse on the ins-and-outs of anal pleasure, and where to go (within) to find it. Known for such virtuosic and controversial dances as the men’s “ass duet” in Fort Blossom (2000, 2012), Jasperse revealed his depth of knowledge on the subject. For instance, I did not know that the pubo-rectal sling existed, or that it is one of the most powerful muscles in the human body after the tongue. I also never thought of Kegel exercises for anal health, but learned they can be used to locate, contract and release the muscles of the sphincter, which I now know after the group exercise with John and the entire audience. Passing around a small photo album of male strippers and go-go dancers, choreographer Ishmael Houston-Jones read from an alphabetical list of the men who worked at the famed yet extinct Stella’s. The portraits he created from his memories of these men were humorous, dark, and moving. Though Houston-Jones was familiar with them by proximity, he never knew these men on a personal level. However, the detail with which he could describe a body, persona, performance, or his own curiosity brought the atmosphere of the club back to life, and communicated an intimately-lived experience of New York, decades past.

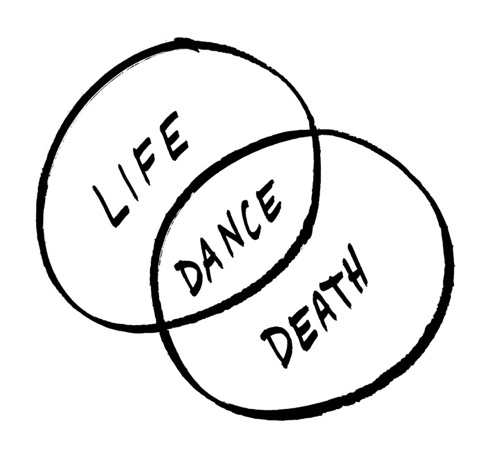

A logo of the Bureau for the Future of Choreography.

June 2: This final day of events began with a Sensory Walk through Central Park with choreographer and iLAND founder Jennifer Monson, flowed into a picnic for artists with children hosted by choreographer Anna Sperber, and then resumed at the Center at West Park. For the duration of the festival, The Bureau for the Future of Choreography hosted a studies project,”WHAT IS CONTEMPORARY DANCE and WHERE DOES IT COME FROM and WHERE IS IT GOING?” an interactive installation where visitors created their own flowcharts of dance history, and contributed to a room-sized, decade-to-decade timeline from 1960 to 2020. This iteration of the project culminated with discussions and presentations by international dance scholars.

Dynasty Handbag as beat poet as historian as queer theorist. Image credit: Ian Douglas.

Jibz Cameron brought the festival to a close with her performance of Dynasty Handbag, covering dental hygiene, American History, Sophie B. Hawkins‘ denial of being gay in the 1990’s, and the Beat poets. Known for her radical performances that utilize her own pre-recorded voice as a second persona, original songs, facial distortions, and a movement vocabulary all her own, Cameron traveled through time, interweaving narratives of depression and avoidance behavior with lessons in queerness, history and poetry. After channeling Beat poet personas Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs in a raging satire, the performer made a “dance,” looking smug in her attempts to execute a contemporary dance. Though it was clear that she was personifying tropes of dance with a varying degree of success, she was still dancing. It seemed an appropriate conclusion to a festival of dance that didn’t stay fixed on any one definition of the art form.