Watching artist Kenny Scharf paint a monumental, public mural entirely by himself on a very cold November night in New York City, I was astonished not only at Scharf’s free-hand skill, but also his artistic drive, painting character after character, to create a bright, smiling beacon of fun on the Bowery.

After witnessing Scharf painting tirelessly, there was no question in my mind that Scharf not only refuses to use a team of assistants to make his art but also, devotes himself completely to his art-making process, fitting perfectly with the theme of my two week residency at Art 21.

Working continuously since the early 1980s in New York, Scharf is only beginning to receive the critical recognition that he deserves for his long and varied career. Often lumped together with his friends and fellow artists Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat, Scharf’s work has progressed past the art of the 1980’s to become a testament to his own enduring aesthetic, marked by happy characters, Hanna-Barbera cartoons, customized appliances and futuristic outer-space scenes.

With art ranging from paintings to sculptures to murals to Cosmic Cavern installations, the largest being his basement space in Brooklyn, which he turned completely into a black-lit, day-glo world where he holds dance parties and performances, Scharf’s body of work stands as an example not only of long-term artistic creation but also, proof that art can and should be fun.

I spoke to Scharf about his artistic process, the role of spontaneity in art, the B52’s and how he feels about the legacy of art of the 1980s.

Emily Colucci: For these two weeks at Art 21, I’ve been focusing on the artistic processes of artists who do their own work and devote themselves entirely to art-making. What is your artistic process?

Kenny Scharf: I believe in doing the work myself. I don’t have anyone helping me other than stretching and gessoing the canvases. The actual art-making, I do all myself. It’s not that I don’t think anyone else could do a good job. It’s what I love to do.

There’s a million definitions of being an artist but I really like to see the artist’s hand. Not only in what I do, but when I look at other artists’ work, I really respond to the emotion and the energy that comes from the line or the mark the individual makes. If you’re hiring 50 assistants, you’re not going to get that same passion that the individual behind it would. I believe in the power and the passion of the actual touch.

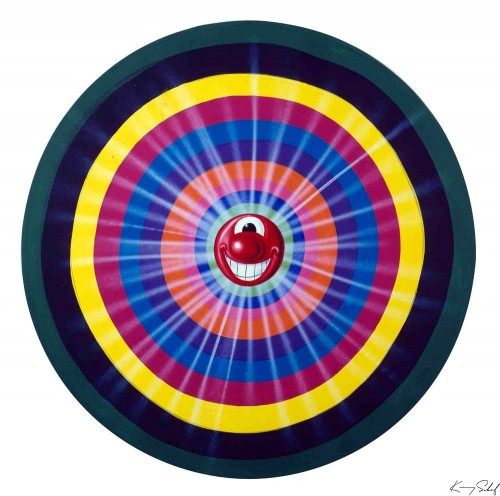

Kenny Scharf. "Starring the Star, " 1985. Oil, acrylic and spray paint on canvas (via kennyscharf.com).

I’m very old-fashioned in a way. I do oil painting on canvas, something that’s happened for centuries. Not that I’m against using new technologies, but I’m really into the old way. I like the tactileness of making it myself.

I’m not really a business man; I’m an artist. Almost everything I do is spontaneous and that’s something you have to do yourself too. I think a lot of the magic happens when you don’t know what you’re going to do. You just let fate guide you and the use of magic. You depend on another kind of energy or something outside of yourself. It’s kind of a scary thing and it’s really exciting. I really believe spontaneity and magic come together.

EC: Most of your work is about fun, from donuts to The Jetsons and The Flintstones, to your own happy characters. Does the spontaneity of your process create fun on the canvas, mural or installation?

KS: You can’t plan fun out because then it’s not so much fun anymore. The spontaneity when you just don’t know what’s going to happen, that’s what’s fun.

EC: In addition to your canvases, you have done many large scale public murals in many locations, from New York to Miami to Philadelphia. Do you plan these murals or do you continue to let the art and fun spontaneously happen?

KS: People always ask and when I tell them I don’t plan them out, people don’t believe it. There’s no drawing or projection. You’re relying on chance and it’s super exciting to do something like that in public in front of everyone. It becomes a performance. It’s always both exciting and scary. You have to take those risks for the magic to happen and you can always fall on your face in public. You have to have faith and it’s worked so far for me.

EC: I interviewed performance artist Hunter Reynolds for the Art21 Blog and he revealed that he sees all of his art-making as performance-based, even painting. Since you notice your mural painting evolve into a performance with a public audience, do you see other parts of your work as a performance?

KS: It all depends. I guess if you’re all alone, it can still be a performance. Everything you do is a performance. You’re your own reality TV show even if there is no camera. Everyone is, all of the time.

EC: In addition to drawing and painting, you also make installations, the biggest being your Cosmic Cavern space in Brooklyn, a day-glo, black-lit world created from disco-balls, appliances, toys and any other material you can glue to a wall. Do you rely on spontaneity to construct these installations?

KS: It’s not a lot of planning. It’s like I have this vacuum cleaner and this dinosaur. Let’s put it together and throw it over there.

EC: Entering into a Cosmic Cavern, you really get the sense that you are walking into a Kenny Scharf painting. When did you start constructing them?

KS: I started doing it a long time ago, probably around 1981. I had this this weird place right near Bryant Park back with Keith Haring then, it was very funky. It wasn’t a loft. It was an 1820’s townhouse that had never been repaired. It was stuck between these buildings in Midtown. I discovered this room in this rambling house. It was so filled with junk that you couldn’t even get a foot in the door. I thought, “Okay, I have a new space here.” So I emptied it all out. It had old wallpaper and was all funky, abandoned and cool. I don’t know exactly how I stumbled on a blacklight. I was walking and I saw a blacklight and thought, “I need that.” I put it in the room with a poster and combined it with all the junk I had just took out of the room. This was all connected to my fascination with junk and garbage. I had been making art out of trash for awhile before that. I like appliances and things with dials and toys, things I can transform into these science fiction/fantasy objects. I started throwing the junk in the room and painting it fluorescent with the blacklight. So, it all grew from there.

People didn’t look at what I was doing as very original because blacklight was very popular in the ’60s with the hippie culture. In the ’80s, it was kind of weird to bring something back that was already from another generation. But I didn’t care. I loved and I still love what blacklight does to a space. It’s a change of reality to look at those colors and the intensity. Obviously I’ve done something different with it but it still goes with the same spirit as the ’60s, blacklight installations, which were less about art and more about nightlife and happenings.

Then, parties started happening in them. I love having art that you can dance in. It becomes alive. Visual art itself is alive, but when you have music and people, it’s a great performance. Then, when Michael [Michael Alan has performed several times in Scharf’s Cosmic Cavern space in Brooklyn] did his shows in there, it’s another crazy dimension. It’s very exciting to host a space where you see great things happening by other people. There is so much time that I spend by myself making art. Art is so solitary that when you get to do something involving a party and a bunch of people it’s great.

EC: Since you do host dance parties in the Cosmic Cavern with a soundtrack ranging from funk to Martha and the Vandellas, what sort of music do you listen to in the studio?

KS: I’m kind of lazy. I used to listen to a lot of my friends’ mixes. Scott Ewalt made great CDs, but I usually just listen to internet radio. I listen to Michael’s CD [Michael Alan Alien], it’s a lot of fun. I like everything. I listen to the jazz station when I’m in New York. I like it all really.

Kenny Scharf. "Cosmic Donut," 2008. Silkscreen with crystal glitter on illustration board. Courtesy of Paul Kasmin Gallery.

EC: When I think of your work and music, I can’t help but think of the B52’s. With both you and the band’s focus on a 60’s, futuristic aesthetic, your art and their music seems to go together perfectly in my mind, which culminated in the album cover for “Bouncing Off the Satellites” you created for them.

KS: They’re my favorite band ever! From the first day, Keith Haring and I were just groupies. If you watch any of the early videos you can see Keith and I sweating and go-go dancing at the very front. There’s more than one video like that out there.

When I first saw them, I was like, “Oh my god, this is the musical counterpart to my art.” Even the song “Planet Claire.” I had just done my first show and it fit almost perfectly to the words of the song of this girl who gets in her car and drives to outer-space. I felt very connected immediately. All I wanted to do was to do everything for them.

Kenny Scharf. "The New and Improved Ultima Suprema De." Car/mixed media. Courtesy of Honor Fraser Gallery.

EC: Speaking of driving to outer-space in a car, I saw the painted Cadillac you made for your recent exhibition at Honor Fraser Gallery in Los Angeles. When did you start making your painted Cadillacs?

KS: My first car when I got some money from my first show in the ’80s. I bought a ’61 Cadillac. It was the first car that I painted.

It really started with customizing appliances. I look at a car as one of the ultimate appliances. Whether it’s a car, a TV, a telephone, anything that you actually use and handle and touch, if you turn that object into art, then you bring art into your everyday life. I look at it as futuristic but also it’s very ancient. I compare it to the Ancient Egyptians or the Greeks. All their objects that they used in their daily life were art. They didn’t have TVs so they used urns. Its pretty similar to the ancient way of living and I think it elevates you.

If you live in a state of art, you’ll be elevated.

EC: It seems that many artists, writers and others in the art world now have a real nostalgia for art from the 1980s, from the art to the clubs such as Club 57 to the alternative spaces and exhibitions such as the Times Square Show, of which you were a part. How do you feel about this current nostalgia for art since you played such a part in that art scene?

KS: It’s amazing. You can only hope that as you get older, younger artists will look at what you do for inspiration. When I first came to New York and decided, “this is it, I’m going to do this,” I was looking at Warhol and his life, happenings, the Pop artists and everyone who came before me. I can only dream that I could make that impact in any way on younger artists. Its important to have that. No one lives in a bubble. Work hard to keep the line going. If I can offer some kind of line like that, I’d be very happy about that.