Martha Wilson, I Make Up the Image of My Perfection/I Make Up the Image of My Deformity 1974, color photograph, text (Courtesy of PPOW Gallery)

Concluding my guest blogging residency at Art 21, where I’ve looked at the processes of artists who both produce significant bodies of work without a team of studio assistants, and dedicate themselves completely to their artistic visions, performance artist Martha Wilson not only concerns herself with the creation of her own work, but also the preservation and support of other avant-garde artists, as the founding director of the not-for-profit alternative space and organization, Franklin Furnace.

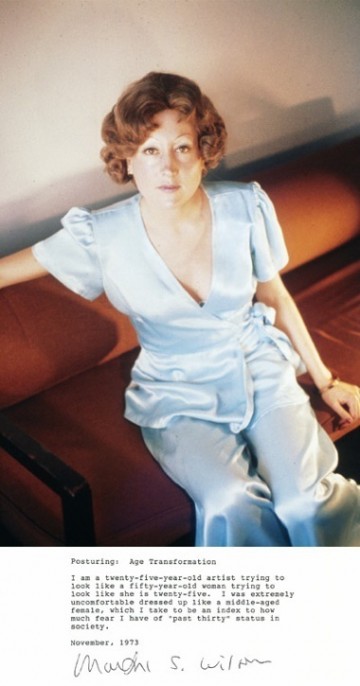

More widely recognized through her work with Franklin Furnace, Martha Wilson’s art has steadfastly focused on women’s subjectivity and the performance of gender. From early photo-text pieces, where Wilson dressed as a man who is impersonating a woman, to her performances as First Ladies Nancy Reagan and Barbara Bush, to her most recent works, in which Wilson revisited the framework of her early photo-texts to investigate the role of a woman over 60, Wilson stands as an artist whose strong and humorous voice has endured and remained current through many waves of feminism. With 2011’s I Have Become My Own Worst Fear, her first exhibition as an artist represented by a commercial gallery (PPOW Gallery), and a recently-published monograph, The Martha Wilson Sourcebook, Wilson’s art is currently receiving the critical attention it deserves.

I spoke to Martha Wilson at the Franklin Furnace office in Brooklyn about the evolution of her art, her relationship to feminism, absurdity in art, and the Culture Wars.

Emily Colucci: For these past two weeks on the Art21 Blog, I’ve been focusing on artists who I find inspiring both in their refusal to use a team of assistants to create their large bodies of work, and their unquestionable devotion to their art–as with your work, both as an artist and as the founding director of Franklin Furnace, the not-for-profit organization concerned with the support and preservation of avant-garde art. What is your artistic process?

Martha Wilson: A year ago, I was invited to join the PPOW gallery and as part of that process, Jamie Sterns, who was the director at that time, wanted a photograph of my studio, which set me back because I don’t have a studio. So instead, I took a picture of my desk. That’s where all the magic happens, where I sit and think.

EC: Did you ever have a studio?

MW: No, I wanted to be a performance artist because you don’t have to have a studio. You don’t have to pay rent, you don’t have to worry about storage, you don’t have to have studio assistants. You don’t have the infrastructure. As the director of a not-for-profit, I had the advantage of having the loft above Franklin Furnace. I did have a studio in that regard. At least, it was a big open space.

Martha Wilson. "Posturing: Age Transformation," 1973. Color photograph, text. Courtesy of PPOW Gallery.

EC: Even though it’s always based in performance art, your work has gone through a few different evolutions over the years. How would you describe the progression of your artwork?

MW: The work that I started doing from 1971-1974 was photo-text work. I had the concept and then, I would either take the photo myself or have someone else take it for me to find out how the experiment was going. Someone had to take a photo for me so Richard, who was the boyfriend who looked like Marcel Duchamp, who dumped me, did so.

Then Richard dumped my ass and I moved to New York. I decided if I’m going to put my personality together I’m going to do it in New York. I found the feminist movement and discovered the most marvelous, welcoming environment to land in. I started an all-girl band, Disband, which was made up of members who couldn’t play instruments. At that time in the 1970s, everyone was in three bands in the no wave scene. Then, Disband disbanded.

I was doing these live performances as the First Ladies, starting with Nancy Reagan. For decades, my studio consisted of a suitcase where I would carry my heels, my hose, my suit, my wig, my pearls. I still have that suitcase.

Then, Mitchell Algus discovered me in 2008 and asked if I could look back at my work from the 1970’s. So I pulled everything out from under the bed. And my friend said, “Now that you have a dealer you have to ask him for another show.” I didn’t really have any new work, then I thought I could revisit the information in the photo-text works from the perspective of a woman north of 60 years of age.

Martha Wilson. "Growing Old (Chrysanthemum)," 2008-09. Pigmented ink print on Hahnemuhle bamboo paper.

EC: In these photo-text works, both the works from the early 1970s and the recent pieces, you use photography, yet you consider yourself a performance artist. Are these photographs the documentation of a performance?

MW: The piece itself is the embodiment of the idea and concept. Even though the event is in the rear view mirror, we can refresh it by looking at the project’s text and photo.

EC: You referenced briefly your performances as the First Ladies, starting with Nancy Reagan and progressing to Barbara Bush, which you recently performed at the Visual AIDS Benefit. You’ve also performed as Tipper Gore. What inspired you to become Nancy Reagan and start out these series of performances?

MW: One of the first things Nancy Reagan did when she got to the White House was order new china. The country was in a recession at that time. New York was going bankrupt in 1976. But, Nancy was having a ball.

The other thing she did was she got advice from an astrologer and was trying to guide White House policy with advice from the astrologer, which hit the front page of Time magazine. We still don’t know whether Reagan was the brains of his own operation. Maybe, like George Jr, he had someone in the background, but here was Nancy buying china, wearing [expensive] clothes, and being totally oblivious. So I thought I could make her say anything I wanted in that vacuum.

[vimeo:https://vimeo.com/21574747]

EC: With work dealing with women’s subjectivity and the embodiment of certain gendered roles, even the role of the First Ladies, do you consider your work feminist?

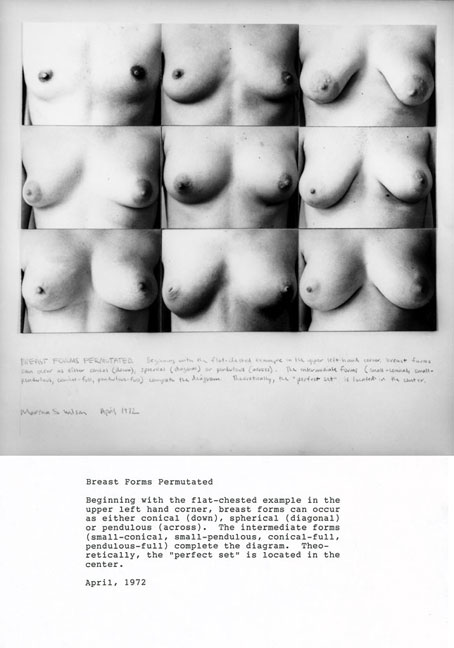

MW: In the early days, I was coming from the point of view of being a female in a male-dominated art school environment. For example, Breast Permutated is a take on Sol Lewitt, who was doing all those permutations. At that point, I didn’t have a consciousness-raising group or even any women friends. I didn’t have any infrastructure and didn’t use the term “feminist.”

Martha Wilson. "Breast Forms Permutated," 1972. Black and white photograph, text. Courtesy of PPOW Gallery.

Then, I moved to New York in the 1970’s and the term feminism was being openly discussed. Women were questioning what is that, and what is a feminist supposed to act like, and look are you supposed to wear makeup? Do you yell at other people? How do you feel about pornography?

I started to use the term feminism pretty soon after. I knew I didn’t want to specifically say that we are going to privilege women in the program of Franklin Furnace. Over half of the artists shown at Franklin Furnace have been women, but we just let the chips fall where they fell.

EC: The art world has undeniably changed for women artists since you first started making work in the early 1970s. How do you think the role of women in the art world has evolved?

MW: The situation now is so much more nuanced and complex then it ever was. Back in the day, it was men=bad, women=good. It was easy to rail against patriarchal society or to create an artwork that critiqued the role of women and men. Now it isn’t easy. Gender has gone all over the place.

EC: When I look at your body of work, I can’t help but view your work through the lens of several various types of theory, from feminist, queer, performance and postmodern theory. For example, your play with gender identity in your early photo-texts resembles Judith Butler’s theory of gender performativity, even though it pre-dated her text by almost two decades. What do you see as the relationship of your work to theory?

MW: I never read a stick of theory. I just felt my way out of the hole that I felt I was in. Now, I have Judith Butler on my bookshelf but, I don’t do theory first. I do experiments but it’s not quite the same. Those people are much smarter than I am.

EC: Most of your work, from the First Lady performances to the Marge/Martha/Mona, a portrait of you as a Marge Simpson-Mona Lisa, is very funny. Do you see humor as an important part of your art-making?

MW: I see it as an important part of life. I like the word absurd better. In the Martha Wilson Sourcebook, I was going to put a passage from a Faulkner novel called Absalom Absalom! where a girl is raped by a corncob. You read this passage and your mouth opens, your eyes pop and you don’t know whether to laugh or to cry. That’s my goal. The tipping point between laughter and sobbing is really where I’m at.

EC: Looking to Franklin Furnace, Franklin Furnace was one of the alternative spaces that got caught up in the Culture Wars of the late 1980’s and early 1990’s. In 1992, Franklin Furnace’s NEA grant was rescinded after being criticized for hosting several “obscene” art pieces, such as Karen Finley’s “A Woman’s Life Isn’t Worth Much.” What was it like to play such a large part in the arts community that was demonized in the early 1990’s?

MW: Culture-Wars-R-Us. I didn’t see it coming. In 1984, we hired a consultant who said, “You really shouldn’t show that stuff,” and thought, “buzz off.” Everyone gets naked all the time; this is the avant-garde. But then the Religious Right found us and was like “Yay! Oh my God, they get naked all the time.”

The first thing that happened in the Culture Wars was when the critics’ fellowship was eliminated. What we didn’t understand was that it was the first step in a long train. Silence the discourse and then, silence the artists themselves.

EC: Looking back to the Culture Wars then and its relation to the controversy today– with works such as David Wojnarowicz’s A Fire In My Belly being removed from the National Portrait Gallery–how do you see the legacy of the Culture Wars 20 years later?

MW: The good new is that it’s no longer possible for an institution to take something down without a public outcry. And that’s positive. At least, it hit the paper and people thought and talked about it. There was some debate. That’s better than assuming it’s perfectly ok to take [an artwork] down because it’s morally corrupt.

EC: In my previous Art 21 Blog interview with Kenny Scharf, we discussed the nostalgia that seems to be swirling around both the alternative spaces and the art of the 1970’s and 1980’s in New York. Being the founding director of Franklin Furnace, one of the significant spaces of that period, and an artist connected with the Downtown New York scene, how do you feel about this nostalgia?

MW: At the time it did not feel like a golden age, we were very poor. The rents were cheap but we were making so little money, it wasn’t cheap. I had three roommates at Franklin Furnace in the early days.

The nostalgia takes various forms. There’s kind of a nostalgia for the aesthetic of the time, the nostalgia for the first glimmers of postmodernism before we knew what that was. We were doing something that was called “postmodernist” at a later point.

People ask me all the time, “What kind of standards should I use to preserve stuff?” And I tell them, “That’s not the important question. The important question is, is there anything to preserve. Is there anything of any kind: photos, videos?” If you just hang on to it, it become the subject of nostalgia and also a text of what happened then. Providing the means for people to feel nostalgia is what we’re doing at Franklin Furnace.

Pingback: Currently on view | Portrait Society Gallery

Pingback: The Personal is Political: MARTHA WILSON AND MKE | Portrait Society Gallery

Pingback: The Personal is Political: Martha Wilson & MKE : RANDY

Pingback: Transcend The Skin You’re In At P.P.O.W.’s ‘Skin Trade’ | Filthy Dreams

Pingback: Meet Martha Wilson! — The Art League Blog — Alexandria, VA