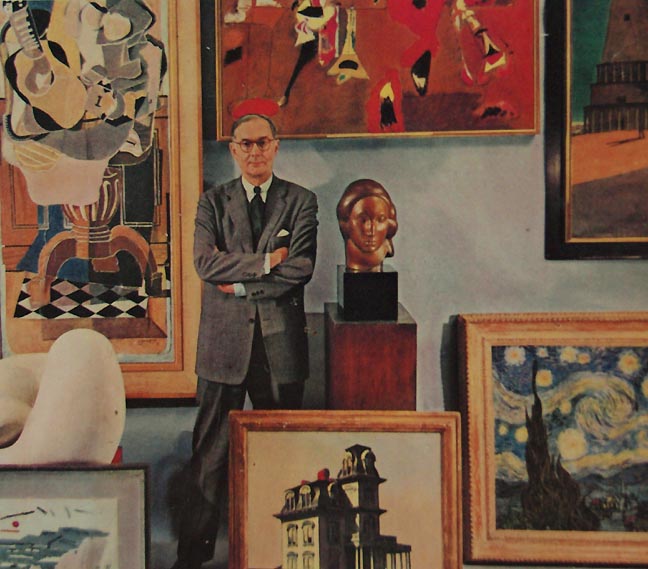

Because of Prohibition, Margaret Barr had never had much more than a glass of sherry, and only on rare occasions. But she learned how to make Old-Fashioneds when her husband, Alfred Barr, was fired, or “forced to resign,” from his job as director of the Museum of Modern Art. It was 1943, World War II was on and Barr, who was the first director of MoMA and famous for championing Picasso, got the letter on a Saturday morning. When Margaret wanted to go to a movie with their six-year-old daughter, Barr went along but was in a “ghastly mood.” He showed her the letter when they returned.

It was from millionaire Stephen Clark, the chair of MoMA’s board of directors, and it said that he and Mrs. Rockefeller had decided that, really, all Barr was good at was writing, not curating or directing. And so he was being asked to relinquish the directoral job and stay on to write things if he so chose, but, of course, at a greatly reduced salary. Barr stayed inside the house for days, in despair, writing responses to Clark that he never sent. Said Margaret:

I still remember seeing him lying on the couch in the living room — still everything is exactly in the same place in our house to this day — lying on the couch. . . always in his pajamas and bathrobe. I remember kneeling beside him and offering him an Old-Fashioned in order to make him drink something so that he would eat something. It was unbelievable.

As the story goes, MoMA had hung a show by new primitivist Morris Hirshfield, with awkward, “offensive” nudes. Stephen Clark had not liked this, nor had critics. Or perhaps Clark hadn’t liked it because critics hadn’t liked it. I’m not sure. Regardless, the board forced Barr out, even though he’d made the museum what it was.

It’s probably not unfair to say Paul Schimmel made MOCA what it is – or what it has been the last decade and a half. After all, the museum’s still more or less an adolescent; it only opened in 1983. Schimmel curated at MOCA for more time (22 years) than Barr directed MoMA (14 years). The MOCA board forced Schimmel out on June 28 (they say he resigned, which is what Clark said when Barr was on the couch being force-fed Old-Fashioneds).

The one conversation I have had with Schimmel was after painter Cy Twombly died. Schimmel talked about visiting Twombly in Italy and sitting at a café, fielding questions about contemporary L.A. artists. What about Mike Kelley? And Paul McCarthy? What were those guys up to?

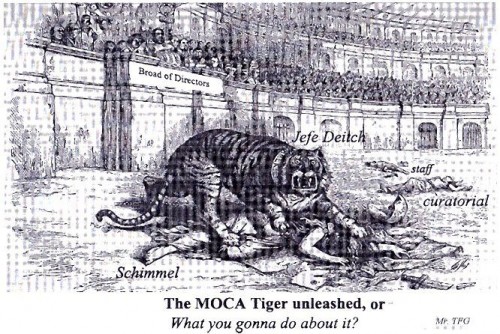

Schimmel was the one to ask. He’d been in SoCal (he started at the Newport Harbor Museum of Art) since Kelley’s career got started, and he’d help both Kelley and McCarthy become “established,” even “iconic” with his 1992 extravagnza of a show “Helter Skelter.” He also just loved them and other L.A. artists. “When you love something, you love it unconditionally,” Schimmel wrote in a letter he posted on Facebook (more recently, he’s posted an old, 18th-century-style cartoon of MOCA director Jeffrey Deitch as a tiger, eating him alive).

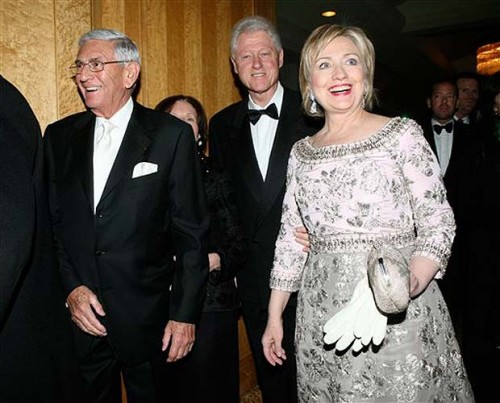

Hillary Clinton with Eli Broad at a dinner to celebrate Obama's inauguration. Photo by Diane Bondareff.

This weekend, when the Sunday paper came, there was an editorial by Eli Broad, a billionaire and lifetime MOCA trustee, by far L.A.’s biggest art-focused philanthropist. It was right below a piece on Hilary Clinton’s diplomatic track record and titled, “MOCA’s past and future.” Broad wrote about Schimmel’s “resignation,” said everyone knew Schimmel was a brilliant curator, then vaguely implied that shows under Schimmel really had not been cost effective – he was vague about Schimmel’s implication, that is, not about the fiscal part. Broad said, “I applaud the decision of MOCA’s director, board leadership and board in right-sizing the staff and adopting a budget that they expect will be balanced in the coming year and in future years.” He also defending his 2009 hiring of populist Deitch and said, “In today’s economic environment, museums must be fiscally prudent and creative in presenting cost-effective, visually stimulating exhibitions that attract a broad audience.”

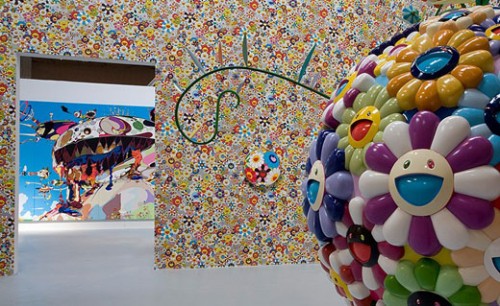

The cost-effective part makes sense. MOCA’s been a financial disaster for years, and exhibitions that put it further into the hole would unarguably be counter-productive. But “visually stimulating”? What does that mean, exactly? Does it mean the recent off-site James Franco-curated show, where red paint that resembled blood was smeared all over really expensive-looking replicas of bungalows from the famous Hollywood hotel, the Chateau Marmont?

I always apply the “dad test” when I go to an exhibition and am trying to decide if, had I not spent years studying this stuff, I would still care. My dad knows Picasso and Van Gogh, but I don’t think he’d be able to pick out a Matisse. Still, he’s a smart, curious guy, so if he’d like a show, I feel like a fair number of the other smart and curious people in the world would too. My dad would be a little confused by the Land Art show at MOCA right now, a last vestige of MOCA as it was before Jeffrey Deitch stepped in as director, though he’d like the earth installed high on the wall and the video of Jean Tinguely blowing things up in the Nevada Desert, at least for the first few minutes. I imagine my dad would have liked the Street Art show, Deitch’s biggest hit to date (I appreciated the effort, but didn’t like it – I wished it had been installed differently, had positioned the movement differently, highlighted some people it downplayed). But he would have been appalled by the Franco show, and annoyed by the Mercedes Benz in the week-long Transmission L.A. festival.

Visually stimulating? Does that mean flashy and brazen, and is that what people want, first and foremost? Yesterday, on July 11, a letter by three other MOCA lifetime trustees—Lenore S. Greenberg, Betye Burton, Audrey Irmas and Frederick M. Nicholas—was published in the L.A. Times. It was titled, “A Different MOCA.” It read:

Restoring the artistic and curatorial integrity of MOCA is crucial in regaining its respect and prominence. MOCA has not shepherded its finances well; it has overspent and is now paying the price. But bringing down expenditures does not mean bringing down the caliber of its exhibitions as well. The celebrity-driven program that MOCA Director Jeffrey Deitch promotes is not the answer. . . . There is support in the art community for MOCA — not as it is now but for what it once was and what it can be and must, in the future, again become.

We’ll see what happens. MoMA figured out how to do some great shows even after Alfred left the helm.