Danielle Adair. "Oh—Say Can You See," 2003. Still from video. Courtesy the artist.

Buried at the bottom of Danielle Adair’s online selection of performances and works is a video titled Oh—Say Can You See (2003), which was done as a response to President Bush’s controversial “Mission Accomplished” banner and speech during the Iraq War. In it, the artist walks into a nondescript industrial setting with a stack of handwritten placards, each one containing a prepositional phrase from our country’s national anthem, such as “by the” and “what so.” In imitation of Bob Dylan’s well-known video for the song “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” Adair proceeds to peel away the placards one by one. There is no music in the video, just the whistle of wind as Adair throws the cards to the ground while puffing on a cigarette. Two random passersby exit the door behind her before the video is over.

Adair laughs at the video now and says it’s on her website for comic effect. It is one of the works that got her into the graduate fine arts program at Cal Arts in 2005, and as such, it serves as a significant marker on what some would see as an unconventional career path. As an undergraduate at the University of Chicago, Adair was majoring in Comparative Human Development, a unique interdisciplinary concentration that looks at multiple facets of human social life, before she stumbled upon a class in early video art, taught by artist Helen Mirra. The possibilities opened up by that class inspired her to complete a second major in Visual Arts, and to this day, Adair thinks of video as “the forum through which I think.”

After graduating, Adair taught English in the Czech Republic for one year and worked at an assisted living home for another. At some point, it occurred to her that she should pursue an advanced degree in art; in her words, she “kind of subconsciously knew that I was going to go into art.” She put together a portfolio that essentially consisted of a few videos and a few sculptures. The conceptually-oriented Cal Arts accepted her on the first go-round.

I asked Adair if she thought her practice was under-developed when she first entered Cal Arts. The question seemed to be a bit of a non-question for her: “It’s hard to think of it in those terms. The nature of my practice is always exploratory, trying out new things. So yes and no. It’s like, if you’re a writer, you go back to old notebooks or old assignments and you have this idea that you’ve since progressed in style, logic, quality of argument, etc. But when I go back into old journals from ten years ago, I think whoa, that sounds like me now, did I just write that yesterday? When I was studying psychology, I remember the grad students would always say, ‘Everything we experience in the first 20 years of life influences everything after. It’s all in those years.’”

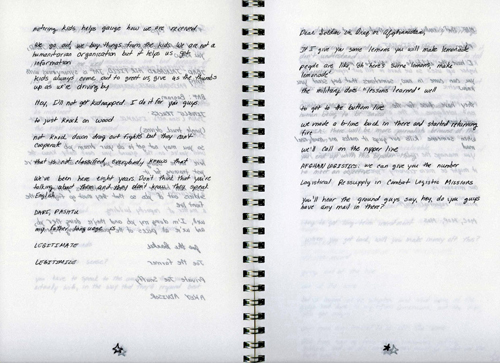

Pages from JBAD: Lessons Learned, Les Figues Press, 2009, ed. of 100.

In other words, Adair was always already what she is now. In the early video, you can see the interrogation of language and the questioning of political mantras that still inform Adair’s work today. When I first met Adair back in December 2010, she was performing a cracked reading of Walter Kronkite’s 1968 Tet Offensive television editorial, inserting contemporary references into Kronkite’s impassioned diatribe. She was also coming off of an incredible project in which she successfully got Los Angeles–based literary publishing house Les Figues Press to propose her as an embedded journalist in Afghanistan.

After spending a month living in Jalalabad and Kabul, she produced a series of literary, video, performance, and installation works collected under the banner First Assignment. This includes the 2009 Les Figues publication From JBAD, Lessons Learned, which essentially compiles all the words and phrases she heard on the base that had military significance or meaning. Published in a format that mimics the look of the U.S. Army and Marine Corps’ Counterinsurgency Field Manual, Adair’s book is a sort of conceptual artist’s field guide to Afghan operations. She has also used it as a script for performances.

When not confronting the languages of political conflict, Adair’s work also frequently engages with the poetic nuances of the everyday. The most recent series, which she calls And I Think I Like It., is largely comprised of short video animations accompanied by original text (sung by the artist) and music. Each one takes an inventory of quotidian objects and/or ideas and re-examines the rhetoric that customarily accompanies them.

For example, Hope May (2012) is a piece that was inspired by Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign. Over a sung chorus of “hope may come,” Adair recites every sentence beginning with the word “hope” that she received or sent in emails during the month of May 2008. The resulting litany of sentiments occupy a broad spectrum of the banal, from “Hope to see you soon” to “Hope the delay in delivering your acceptance notification will not cause you any difficulties.” The video’s graphics include an abstract painting incorporating stars and stripes and the frequent appearance of gesticulating, disembodied arms—these evoke the feeling of a staged hat trick, a dubious theatricality. The word “hope,” invested with so much weight by the Obama campaign, is shot through and deflated here by casual phrasings and suggestions of phoniness and obligation.

The highly evocative Buoys (2012) finds the artist ruminating on gender, sex, and gender roles while a series of drawings of buoys float against a black background as though gently bobbing in water. Along with the pun on “boy,” the buoys also easily resemble phalluses. Like the buoys, the allusions in Adair’s words bob back and forth between racy, philosophical, and conversational. “Where do you like to be touched, where do you like it? Being a boy makes me a woman. Have you ever been with another girl? How have you been?”

Still from "Some People Are Without Guitar," HD video, 2011.

Adair has always been a writer, having completed her MFA at Cal Arts in both visual arts and writing, and her facility with language is impressive. She seems to use it like a sculptural material, another tool with which to interrogate the themes that interest her. She agrees with this assessment and adds, “I like working with a collage aesthetic, although it’s different from the way Burroughs did it with his cut ups. I think we live in an age where we have subconsciously digested such practices. In our era, everything is cut up already, and so my way of navigating the world is to compose the cut up, or to trudge through the cut up.”

She points to another recent video work, Some People Are Without Guitar (2011–12) as an example. “Sometimes it’s very difficult to hear what I’m saying in that piece. I really compose my texts, and I want there to be meaning that proceeds from the words themselves, but I also like the words to be experienced as texture and sound, and I think that is emblematic of my relationship to language as a whole. It’s this thing that has inherent meaning, but there is also a rhythm, a musicality to language, and the way different voices speak language, inflections and all that… I think that’s all involved when I’m thinking of language.”

Adair holds up the piece she contributed to Chain Letter, a group exhibition curated by Doug Harvey and Christian Cummings for Shoshana Wayne Gallery, 2011.