Because of its solid foundation, I am confident that Detroit will have a renaissance in the arts (among other fields). This confidence springs from a community of art enthusiasts who invested heavily in cultural institutions. Images of abandoned buildings steal a lot of the headlines, but the media often fails to balance those images with images of the gilded and ornate buildings that house Detroit’s cultural treasures: The Michigan Opera House, The Gem Theater, The Masonic Temple, The Fisher Theater, the Fox Theatre, and The Detroit Institute of Arts, among many others.

These institutions are as good as or better than they have ever been.

Why do cultural institutions thrive in a city that has so many hurdles? Simply put, because of a community that values culture. Another benefit of Detroit’s strong foundation is the fact that these bedrock institutions educate and inspire future generations of artists and patrons. There are numerous people, both paid employees and volunteer stewards, whose passions push these institutions to provide Detroit and surrounding areas with the culture every thriving community deserves. Detroit’s rich culture flowed and continues to flow to its extensive Metro area, and beyond.

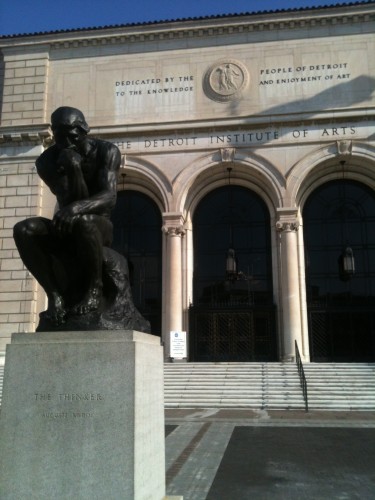

I want to highlight two museums that show the importance of anchor institutions, and that symbolize the delicate relationship between Detroit and its suburbs: The Detroit Institute of Arts and The Cranbrook Art Museum (as part of the Cranbrook Educational Community). These are two of the most influential and widely respected art institutions in the world, and they can both be found on the same street, Woodward Avenue.

The Detroit Institute of Arts is in Downtown Detroit. It anchors the growing Midtown area. The Midtown area leads the fight against the “abandoned Detroit” narrative, namely through Midtown Detroit, Inc. Midtown Detroit, Inc. is a non-profit that has teamed up with anchor institutions in the Midtown Detroit area (Detroit Medical Center, Wayne State University, and the Detroit Institute of Arts) to make this the fastest-developing area in Detroit with the largest growing residential base. The Cranbrook Art Museum is about 20 miles up the road in the affluent suburb of Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, one of the wealthiest cities in the U.S. (Mitt Romney went to Cranbrook’s high school).

Many people do not realize this (including people in Michigan), but the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) has one of the top art collections in the U.S., one that’s in line with those of The Metropolitan Museum, New York; The Art Institute of Chicago; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; and the Cleveland Museum of Art. Once you step inside the DIA, you are in awe of the important, inspiring and historically-significant masterpieces. About 400,000 people visit the DIA every year.

The Institute recently underwent an extensive expansion (it had approximately 600,000 square feet, and added an additional 57,650 square feet) that enables it to show more of its collection. The expansion and renovation also allowed it to institute various installations that go towards its mission to create “experiences that help each visitor find personal meaning in art.” Chief among these installations is the Art of Dining, which allows visitors to sit at an aristocratic dinner service and experience DIA’s collection of eighteenth-century French porcelain, in use by virtual dinner guests.

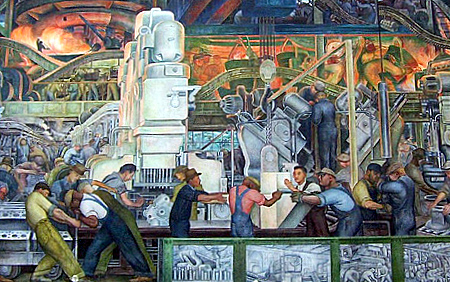

Happy historical facts: the Detroit Institute of Arts was the first U.S. museum to buy paintings by Vincent van Gogh and Henri Matisse. The DIA is also home to the world-renowned Detroit Industry mural by Diego Rivera, who considered this mural to be his most successful work. When installed at the museum, Diego Rivera, his mural, and the DIA’s involvement were controversial. But the museum–led in large part by the son of Henry Ford, Edsel Ford—did not fall prey to the politics of the day and pushed forward to allow Rivera to create a monumental piece of art that continues to inspire visitors to the museum.

Since its opening in 1885, the DIA has been blessed by, and relies heavily on, the kindness of wealthy individuals (almost to its detriment, which I will explain later). One of its earliest supporters was James E. Scripps, a Detroit newspaper publisher who donated 80 Old Master paintings to the museum in 1889. He also shared his love for art and his sense of duty to support the arts with his son-in-law, George Gough Booth (who he also introduced to the publishing industry). George Booth also became a major beneficiary to the DIA. James’s daughter, Ellen Scripps Booth, and George Booth founded the Cranbrook Educational Community, which is a sprawling 319 acre educational community that consists of Cranbrook Schools, Cranbrook Academy of Art, Cranbrook Art Museum, Cranbrook Institute of Science, and Cranbrook House and Gardens.

Last year, on 11/11/11, the Cranbrook Art Museum re-opened after an extensive, two-year, $33 million expansion and renovation. I had the pleasure of talking with resident artist Elliott Earls during the Cranbrook Museum’s grand re-opening.

In line with its impressively renovated building–which now makes the vast archives of the Museum accessible to visitors and students–Cranbrook’s talented staff demonstrated their keen interpretive skills (interpretive skills are those skills that enable a museum to display its work in a way that is readily accessible to the public). The Museum’s re-opening exhibit was titled No Object is an Island. Through this show, the museum paired contemporary artists with historical pieces in their collection to highlight the continuing dialogue in art. Elliot was one of the contemporary artists, and he had an installation piece that was in dialogue with a Rembrandt Peele portrait of George Washington. Elliot incorporated that historical oil painting into his own piece. The Rembrandt Peele piece rested on top of Earls’s super graphics and video, and directly beside his interpretation of the historical oil painting. It was a masterful move by this artist, and the Museum in general, to display the vibrancy of an important art collection.

The Detroit Institute of Arts is similarly successful in its ability to provide meaningful contexts for its exhibitions. For example, the Institute just had a very successful show titled Rembrandt and the Faces of Jesus which created an environment that allowed you to walk through Rembrandt’s life, his inspiration, his city, and to explore his relationship with Jesus.

Interpretive skills are a critical part of a Museum’s mission. Elliott eloquently observed: “I feel the Museum has a deeply important social role … In some ways the idea of the Museum as a repository of musty but beautiful and esoteric crap, is finished… the Museum should be on the frontline in a war for our collective soul. The humanities–those things that make us human–are under ceaseless attack.” He went on to observe that The Cranbrook Museum “should be one essential player in defending a social space for activities that are not economic in nature. The Museum should be a public refuge for the Humanities. The Museum should be a leading warrior in an attempt to claw-back a social fabric that includes the contemplative, aesthetic, and thoughtful.”

This month Dom DiMarco was appointed President of the Cranbrook Educational Community. He retired from Ford Motor Company in 2008, and he was President of Ford South America at the time of his retirement. This is another example of an individual that gives back to our cultural heritage, and another example of industry giants that are up to the task of preserving and expanding the humanities. Dom’s leadership is also a poetic echo to the earlier example of Edsel Ford’s commitment to the arts.

DiMarco explained that, “All of the institutions at Cranbrook seek to motivate students and visitors from diverse backgrounds to strive for intellectual, creative, and physical excellence, to develop a deep appreciation for the arts and different cultures….” He also noted that, “Cranbrook’s Academy of Art is an independent, graduate degree-granting institution offering an intense studio-based experience where artists-in-residence mentor students in ten disciplines to creatively influence contemporary culture. Cranbrook Art Museum is an educational institution that provides students and the public direct experience with modern and contemporary art, architecture and design, and promotes an understanding of their relevance and contribution to society.”

He also noted that “Cranbrook Art Museum continues to preserve the mission outlined by Cranbrook founder George Booth to serve both students and the larger public community.”

The Detroit Institute of Arts and the Cranbrook Art Museum attract and cultivate artists and art patrons in an unprecedented manner, thanks in large part to their earliest supporters. Their shared history and mission help show how–like Cranbrook’s insightful exhibition–no institution is an island. Both would lose a significant partner if either institution was diminished, which would be a disservice to the important dialogue these giant institutions have fostered for decades.

This observation goes towards the cities as well. Both cities can thrive together, or they can meander without one another. Every successful suburb needs an big city to anchor it and which protects and cultivates entertainment. At the same time, every major city needs successful suburbs that provide a comfortable existence for patrons that want a quiet life outside of the city, yet has ready access to the large city’s rewards.

The problem is that while Cranbrook is a private institution that has a regular stream of income from students and a healthy endowment, the DIA is a public institution that has seen almost all of its public funding taken away. The State of Michigan provides zero support. It does not have a significant endowment in line with its operating costs. It has relied on, and continues to rely on, capital campaigns—pleas to wealthy, private companies and institutions—to make ends meet.

Realizing that this approach is not sustainable, the DIA is asking the people in Wayne, Oakland (home of Bloomfield Hills), and Macomb Counties to carry the torch passed to them from those passionate people that have blessed this area with significant cultural institutions. On August 7, 2012, there will be a millage vote where the people the benefit the most from the DIA can bcome patrons of this venerable institution, and help preserve its greatness for future generations (at a cost to homeowners of about $15 per year for every $150,000 of a home’s fair market value).

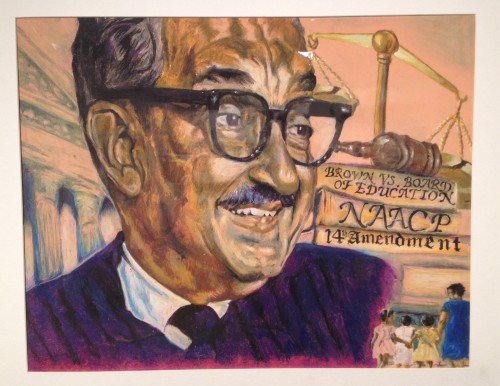

"Thurgood" by Jermaine Tripp (11th grade, Cass Tech High School). This piece was a part of a recent show of Detroit Public School students' artwork at the Detroit Institute of Arts.

ArtServe Michigan recently confirmed what the community knows instinctively: investments in culture have solid financial returns in addition to quality of life and soul returns. ArtServe actually found that for every $1 invested in a nonprofit arts and cultural group in 2009, those organizations contributed $51 back into Michigan’s economy. Those are the hard numbers; the real benefit to supporting an institution like the DIA is that you support an institution that preserves and showcases masterpieces. You get to see those artworks that have the ability to inspire, to leave you in awe, to allow you to marvel at the capacity of gifted artists to speak to those emotions at your core, which allow you to feel truly alive. As Elliot Earls noted earlier, museums are “on the frontline in a war for our collective soul.”

I hope this millage passes, so that we can build on and pay tribute to the cultural base that Michigan is blessed with.

Pingback: Elliott Earls interviewed in Art 21 Blog

Pingback: Art21 Profiles Significance of Cranbrook Art Museum to Both the Metro Detroit and Global Art Communities | Cranbrook Art Museum Blog

Pingback: The Anchor Art Museums in and of Detroit | ArtSibs

Pingback: “The Anchor Art Museums in and of Detroit” | Art21 | Cranbrook Art Museum