One of my favorite places in Guadalajara, art related or not, is currently housed on the top floor of a nineteenth-century house in the downtown area.

The Taller Mexicano de Gobelinos has been in operation more or less since 1968, when it was founded by the Austrian artist Fritz Riedl. It is currently administered by the Ashida family, who also operate Arena México Arte Contemporáneo, a contemporary art gallery.

Riedl arrived in this city in 1967 after having explored tapestry as his main medium since 1948. For the most part, his tapestries reflected his interest in geometric abstraction and were exhibited in venues such as the Venice Biennale, the Sao Paolo Biennale, and Documenta. Riedl lived in Guadalajara from 1967 to 1976, and along with running the tapestry workshop, he was a visiting lecturer at the University of Guadalajara.

Riedl himself trained several young men to be weavers, and some of them still work at the Taller. Though each tapestry’s authorship is attributed to the artist that commissioned the piece, the weavers themselves are involved in every aspect of its creation, as they dye the wool and weave it in order to transpose the image into this medium. Moreover, they are aware that they are not simply copying an image or work of art, but rather, creating another version of it.

The Taller is the sole place in Mexico where this art form is preserved. The history of gobelin tapestries dates to the mid-1400s, when Jehan Gobelin rented a house in Paris to use it as a workshop to dye wool. The workshop eventually began to manufacture tapestries according to Flemish techniques. Henry IV rented the space for his tapestry makers, and Louis XIV made this into an upholstery factory which was in operation more or less until the French Revolution. Though the factory was reopened by the Bourbons, it was burned during the Commune and is now run by the state. The Manufacture des Gobelins currently produces tapestries for the French government as well as preserves this technique.

All of the weavers employed are experts in the “alto liso” (haute lisse) loom typical of these tapestries, or gobelins. It is administered by Renata Trejo and Rafael Morquecho Martínez, the latter one of the original weavers who learned this process from Riedl. Nine other weavers are employed on either a full-time or part-time basis, including several of Morquecho’s relatives.

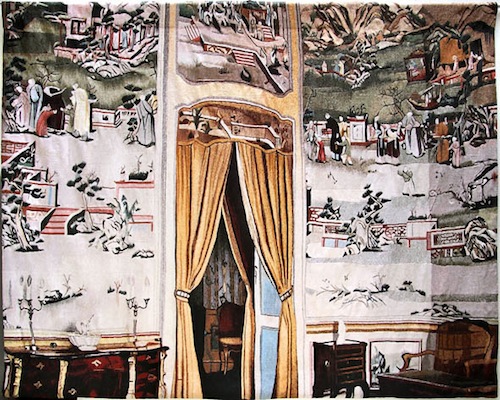

The Taller’s workers have created tapestries for artists such as Francesco Clemente, Sandro Chia, Rufino Tamayo, Juan Soriano, Matthew Antezzo, John Currin, Christian Jankowski, David Scher, Rachel Feinstein, Pae White, George Condo, Greg Colson, Jason Fox and Karen Kilimnik. For the most part, artists request a tapestry based on a work of art they created themselves; tapestries are also made from readymade images.

Other than admiring the individual tapestries, the best way to learn about this practice is to speak to the weavers themselves. I spent some time with Rafael Morquecho, the Taller’s head weaver, in order to hear more about the technical and artistic aspects of weaving. Rafael has been weaving for about forty years, and is very proud of the Taller itself, noting its evolution and its ability to compete with similar workshops in Europe in terms of quality and artistic execution. Beyond his work for the Taller, he also paints and weaves tapestries based on his own designs.

One of the main elements that separate these tapestries from other forms of textile-based art, according to Rafael, are the chromatic effects that can be achieved. The Taller’s weavers usually achieve the required tones by weaving different colored threads at once (rather than one at a time), which leads to more vibrant and richer colors. In a way, it is almost as if they were blending oil paints.

As for the entire process employed at the Taller, Rafael and his brother Leopoldo demonstrated how the wool is dyed, measured, woven, and finally, mounted onto another piece of fabric. They use synthetic dyes, since they are better able to achieve the desired colors with these materials. When weaving, they employ about three threads per square centimeter, significantly fewer than the thirty threads that were used in the past and that some workshops still employ. (Most operating workshops use three threads).

After the piece is finished, it is sent to a sewing workshop to be sewn together, since the individual blocks of color are not fully connected to one another. In essence, the stitches function as lines that bind everything, though this process remains invisible to the untrained eye.

Talking to Rafael, Leopoldo, Renata, and the rest of the weavers made me realize that these are not copies, rather, each tapestry is an interpretation of works of art. In other words, the weavers are not unlike professional musicians that perform their own version of a classical symphony or concerto.

Arena México’s Taller Mexicano de Gobelinos is an establishment that reminds us that Guadalajara’s presence within the global art world is made up of the efforts of a series of devoted individuals who receive little or no government backing. The Taller makes tapestries for artists represented by Arena México and for other artists or galleries.