Barranca Museo de Arte Moderno y Contemporáneo (Barranca Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art), construction site, Guadalajara, Mexico. Photo by JGM.

Despite the fact that much of Mexican contemporary art during the eighties and nineties developed outside institutional frameworks, museums which focus on contemporary art have allowed for further development during the past two decades. While many tourists go to Mexico to visit its archaeological sites, colonial cities and beaches, there are several contemporary art museums both within and outside of Mexico City that are worth knowing about.

Given the centralism that dominates Mexican politics and culture, it is only natural that Mexico City would have the best contemporary art museums in the nation. Beyond that, each of the museums located elsewhere responds to regional specificities. Monterrey’s cultural life, for example, is deeply tied to the interests of its business class, while Oaxaca’s is rooted in its local artists and in the desire to preserve indigenous culture and crafts. Guadalajara’s situation is rather tragic, as it continues to be a deeply conservative city that has been unable to generate institutions that can sustain contemporary art.

Due to its size and scope UNAM’s MUAC (Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo) has arisen as the leading museum of contemporary art in Mexico. It has nevertheless sparked controversy due to its building, which was designed by Teodoro González de León, a leading Mexican architect. Apparently, its similarities to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Tate Modern, and to Kanazawa’s 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art have been noted at home and abroad.

The MUAC is, essentially, the most effective and important public collection focused on contemporary art that combines collecting and exhibiting with several programs aimed towards fostering experimentation and education. In 2012 and 2013, MUAC worked on various types of exhibits by focusing on several areas: modern and contemporary artists and movements; projects by emerging artists; exhibits and publications that incorporate pedagogical research; and large-scale site specific works by mid-career artists.

MUAC’s permanent collection is made up of UNAM’s contemporary art collection, which was formed during the seventies. Its strongest areas include documents and works related to the creation of university’s campus (a hallmark of Mexican modern architecture), contemporary Mexican art, and contemporary photography. One of the most interesting programs sponsored by this institution is related to contemporary practices that go beyond the visual: the Espacio de Experimentación Sonora (Space for Sound Experimentation). Other than providing a space devoted to sound art and related practices, the Espacio counts with the necessary technology to support these projects as well as with a curatorial program that commissions works from emerging artists. This is especially important because there are very few institutions in Mexico that support sound art, or, in fact, new media in general.

During 2012, MUAC hosted or organized exhibitions featuring Michel Butor, Manuel Rocha Iturbide, Fernando Bryce, Akram Zaatari, José Elías Puc, Nicolás Paris, Alberto Cerro, Felipe Ehrenberg, contemporary art by Eastern European artists, contemporary art by Austrian artists, and a group show curated by Néstor García Canclini and Andrea Giunta.

Despite the fact that MUAC has been welcomed as a successful model for contemporary art museums in Mexico, its programs have been questioned, most recently, due to the hiring of a Colombian curator, María Inés Rodríguez. The voices speaking out against Rodríguez have mentioned her links to the Mexican art market, for example. Moreover, the museum does not have a day in which the entrance fee is waived, precluding large portions of the city’s population from visiting. (The museum waived its entrance fee for several weeks during this summer, however).

Although other Mexican cities contain a number of institutions devoted to contemporary art, they lag considerably behind Mexico City’s in terms of quality. In the recent past, the city of Monterrey had an important museum, the Museo de Monterrey, whose collection focused on twentieth-century Mexican art as well as works by Latin American artists. This museum was established in 1977 by FEMSA, a corporation that produces beer and soft drinks, as part of its social programs. Unfortunately, FEMSA announced that the museum would close in 2000 due to the fact that it wanted to redirect its philanthropic efforts. Although the museum was financed by a private corporation, freeing it from depending on public funds, this also left it vulnerable to FEMSA’s whims. Furthermore, the museum was singled out for seeking to legitimize not only FEMSA itself, but several art collections that had been amassed by Monterrey’s citizens since the 1950s.

In many ways, MARCO (Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Monterrey) has sought to fill the void left by the Museo de Monterrey’s closing. Designed by Ricardo Legorreta, it was inaugurated in 1991 and is part of Monterrey’s central urban complex, the Macroplaza. The building itself is typical of Legorreta’s architectural practice, which privileged simple spaces, bright colors and clear structural elements. Legorreta often incorporated works of art by leading artists into his buildings, including a sculpture by Juan Soriano located in front of the museum.

The museum’s collection is heavily weighted towards contemporary Latin American painting, and it complements these holdings with temporary exhibits. Recent shows have featured the works of Mexican artists and others, such as Ernesto Neto, Joseph Beuys, Dominique Lemieux, Dr. Lakra, Jorge Elizondo, Richard Meier, and Claudio Bravo.

The existence of MARCO and its public programs is particularly important for Monterrey, as it is facing an unprecedented wave of violence. One of its most innovative programs is Marcomóvil, a bus that functions as a learning center and roving exhibition space in order to reach different audiences. What seems important here is that art and the ability to learn about it are taken into Monterrey’s citizens’ daily lives, entering their neighborhoods as well as institutions such as schools. This project also seeks to create links between artists and communities, facilitating the rise of artistic projects involving populations that might not otherwise have access to contemporary art.

Although Oaxaca does not have a powerful entrepreneurial class, it has nevertherless managed to open an interesting contemporary art museum, MACO (Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Oaxaca), which opened its doors in 1992. It was formed by citizens led by the local artist Francisco Toledo and is located in a colonial mansion dating back to the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. MACO is set up as a non-profit organization that exhibits contemporary art and seeks to preserve Oaxaca’s rich cultural heritage.

In recent years, it has exhibited works by Joaquín Torres García, Gabriel de la Mora, Daniel Guzmán, Rebeca Méndez, Frank Auerbach, Francis Bacon, William Kentridge, Chantal Akerman, Sophie Calle, Marina Abramovic, Carlos Amorales, Gabriel Orozco, Francis Alÿs and Rufino Tamayo. In 2011, it hosted the Bienal Rufino Tamayo, one of Mexico’s foremost exhibits.

MACO differs from MUAC and MARCO in that it is located in a city that has very strong ties to indigenous cultures, as demonstrated by the museum’s interest in crafts. In many ways, this relationship between contemporary art and crafts is an extension of Francisco Toledo’s artistic practice, as he has been collaborating with craftsmen since the sixties. The museum has also sought to create links with the public at large, as with its 2008 exhibit Reunión Familiar (Family Reunion), which showcased a selection of photographs submitted by Oaxaca’s citizens and by Oaxacans living elsewhere in Mexico and even abroad. Much like Monterrey’s MARCO, MACO reached out to the community so as to address the violence and mayhem experienced by many Mexican citizens during the past decade. Reunión Familiar responded to the teacher’s strike in 2006 and to the rise of the Asamblea Popular de los Pueblos de Oaxaca (Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca), an organization that was created as a result of the governor’s repressive measures against the strike. The exhibit sought to recreate the ways that private citizens had entered the public sphere, since it invited the public to submit their photographs for an exhibition in an institution usually reserved for internationally-recognized artists.

Despite its local and national significance, MACO has not avoided controversy, most notably this past May, when it was accused of censorship. According to MINUS SPACE, a gallery devoted to the promotion of reductive abstract art, MACO cancelled an exhibit of an installation by Lynne Harlow soon after it was inaugurated, for no apparent reason. The artist was reimbursed for her travel expenses, but no explanation was given. MACO did take out an ad at one of the local newspapers arguing that the work had been badly planned as a way to justify their refusal to exhibit it, despite having initially agreed to host it.

As mentioned above, Guadalajara does not have a world-class museum focused on contemporary art, or even one able to compete nationally. This has not been for lack of trying, however. The first effort to create a museum came via the Guggenheim’s proposal to build one of its branches in Guadalajara in 2004. The museum was supposed to launch this city as a cultural destination, much like what occurred in Bilbao during the late nineties. Eventually, questions arose regarding whose collections were going to be showcased and the benefits that would be derived from this. Additionally, public land and funds were granted so as to facilitate the project, which met with considerable opposition.

The effort to build the Guggenheim was abandoned in 2009, soon after Thomas Krens stepped down as director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. This might be for the best, since it appears that the Guggenheim’s franchise model is no longer as attractive as it appeared to be, given Helsinki’s final rejection of it as well as the closing of Berlin’s and Las Vegas’ respective branches.

In the meantime, a new museum is projected to open at the same site, which will be called the Museo de la Barranca. The building itself has already begun construction and was designed by Herzog & de Meuron. The negative issues surrounding it are similar to those that were directed against the Guggenheim’s project, issues that are namely tied to the land and its development, the cutting down of trees, the feasibility of the project, and the private interests it serves. Besides using public funds and land, it appears that, as in the case of the Museo de Monterrey and MARCO, the museum will be closely tied to the interests of private collectors and to an entrepreneurial class intent on using art as a way to gain prestige but without local institutions after which to model itself or a cultural scene able to properly support it. Furthermore, the project seems to be developing at a slow pace and has even interrupted the building process for months at a time, despite the ample advantages given to it.

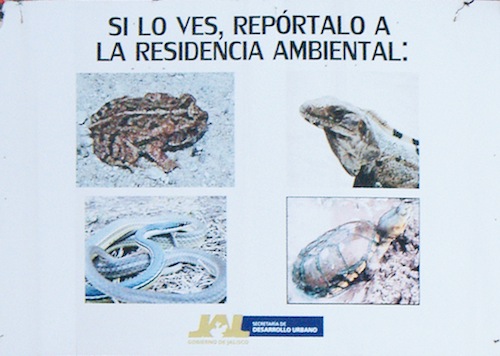

Si lo ves, repórtalo a la residencia ambiental (If you see him, report it to the environmental center), pictures of animals whose habitat was endangered by the Museo de la Barranca's construction. Photo by JGM.

If I am skeptical about the situation in my hometown, this is because, time and again, the private sector has failed to sustain Guadalajara’s contemporary art scene. A tragic example of this was La Planta, which was inaugurated in 2007 as a cultural center financed by one of Mexico’s richest men, Jorge Vergara. This particular space was in operation for less than a year. Vergara claimed that it had to shut down due to lack of interest, which seems debatable, given that the space was open for such a short amount of time. He expressed an interest in continuing to support contemporary art, which he has failed to do as well.

More recently, Taxi Art Magazine and Plataforma Arte, a publication and gallery owned by the same person–which already poses significant ethical issues–has lost several of its key employees due to the owner’s refusal to pay wages promptly. This occurred the same year that the gallery attended three art fairs–ArcoMADRID, Scope Miami, and Zona Maco–all of which charge exhibiting galleries steep fees. It is unlikely that these two projects will last much longer, leaving behind a trail of promises and lost possibilities.

Despite the fact that there is considerable interest in contemporary art throughout Mexico, the regional scenes described above will struggle to gain more national and international visibility without the proper institutions, and more importantly, without art professionals and patrons that behave in an ethical way. One must also remember the fact that the government is centrally structured in a way that favors Mexico City.

In many ways, the current state of contemporary art museums in Mexico is indicative of the lack of importance given to cultural projects of all sorts throughout this country. As was evident in the recent presidential, congress and local elections, contemporary culture is not something public servants are willing or able to engage with as a way to serve their constituencies. Though it is possible for artists to have more or less successful careers without local institutional backing, this closes the doors to many of them, and moreover, severely reduces the number of people that are exposed to the arts.

Pingback: MINUS SPACE | MINUS SPACE en Oaxaca: Panorama de 31 artistas internacionales, Multiple Cultural Venues, Oaxaca, Mexico