George Legendre and Serkan Ozkaya. "Dried Agnolotti" from "One and Three Pasta." Photo by Serkan Ozkaya. Courtesy of the artist.

When I was working on Turkish and Other Delights, people would often tell me about artists who were born in Turkey but who now lived in other countries, recommeding that I try to contact them for interviews. I understood their point well: like gender, place of birth is not destiny; you could be born into one culture or society, but feel yourself more at home in another. Or maybe you move for practical purposes—for example, for educational reasons—and stay as networks grow and harden. All identities are hybrid, nationality included. What happens to an artists’ practice—Turkish or otherwise—when they relocate to other countries? How do the interests and concerns developed as a result of one’s early experiences mutate, develop, grow and change as a result of establishing life in a new cultural context? The answer is of course dependent on the individual, the intersection of their particular personality type, their life experiences, their pre-existing matrix of identities.

I first met and interviewed conceptual artist Serkan Ozkaya in 2008, when he installed a version of his piece A Sudden Gust of Wind at the (now closed) Boots Contemporary Art Space in St. Louis, MO; at the time he was based in Istanbul, though traveling almost constantly to cities in Europe, Asia and the U.S. for exhibitions. When I first arrived in Turkey in 2010, I did a second interview with him in Istanbul; shortly thereafter, he relocated to New York, where he now lives and works.

Installation shot of Serkan Ozkaya's "A Suddent Gust of Wind," installed at Boots Contemporary Art Space in St. Louis, MO, 2008.

For more than a decade, Ozkaya has explored questions related to appropriation and reproduction, through such projects as hand-copying entire issues of various newspapers, exhibiting tens of thousands of slides of artworks together as a public installation, and most recently (and spectacularly) designing and supervising the construction of a 33-foot tall, gold-painted Styrofoam replica of Michelangelo’s David, now permanently installed at the 21c Museum Hotel in Louisville, Kentucky. Growing up in Istanbul in the 1970s and 1980s, Ozkaya lacked immediate physical access to the canonical works of Western art; all he had were reproductions in books, which he then copied. This early experience with replication prompted an artistic and intellectual fascination with the valuation of art, the role of the artist as creator, and the process and meaning of reproduction.

During my time in Istanbul I caught up with Ozkaya via Skype to talk about “David”’s trip from the Anatolian city of Eskişehir (where it was fabricated) to Louisville via New York City; his latest book project; and his current collaboration with George Legendre, an architect, mathematician, and professor of design at Harvard University, which once again takes on questions of design, artistic intention and object valuation, this time by considering pasta as a design object.

Elizabeth Wolfson: So let’s start with “David”’s trip from Eskişehir to Louisville by way of New York. How’d it go?

Serkan Ozkaya: It came on its back from Turkey. People tend to think, when they look at these things, because it resembles a human being, it has feelings like a human being. But it didn’t really make sense with the inner armature and the dimensions; when it’s on its back it extends very far out from the sides, you need escort cars to follow it from front and behind to stop the traffic. Also in that position you can’t really see it as a frontal image, you can’t really see what it is. My idea was always to put it on its side. So in New Jersey when it arrived at the storage space we turned it sideways. That took us one full day. Then we loaded it up on the trailer and took it to the city.

So we went into the city and took our time, moving towards the Storefront For Art and Architecture. Whenever people would notice it they would try to take pictures, but because we were moving it wasn’t easy. So every time we stopped for more than thirty seconds or so people would manage to take pictures. And whenever we would stop for more than a couple of minutes people would try and gather around it. So it was a nice thing when we parked it in front of the Storefront. People really got together.

Then at Storefront we had a panel discussion, which is part their ongoing “Manifesto” series, bringing together different people in different contexts for discussion, and then turning the discussion into a book; mine is the second one. So I’m working on this book, to be called Doubles or Double, I don’t know what the title’s going to be, but something like that. It was really interesting because all these people were invited, Hrag Vartanian [editor of the art blog Hyperallergic], Spyros Papapetros, a really interesting architecture and art historian, they all got together and presented their manifestos on the idea of the double, replica, being a double, triple, whatever. And none of them really had anything to do with my work, which I really appreciated. So the book is really like a reader on this topic.

Those manifesto were pretty fast, five to ten minutes, and after that there was a short discussion, but it was shorter than anticipated because the space was super cold. So later I organized two more discussions, different people, this time in private settings, in homes. We recorded those two discussions with different people, and now I’m editing all these discussions, putting in footnotes, cross references, some things that come to mind—opening it up once again. The discussion is initiated or catalyzed by my work, but it’s definitely not about my work. It’s about this idea that the work triggers. With my editing I open it up once again, with those footnotes, cross-references, that bring in a different context. So I’m really excited about that. That’s all for the new book.

So now “David” is erected, in Louisville. And every week there’s some news, some video. It’s on the news every week. First it was a sensation, it was just news. But now people are ranting about it, people think it’s naked, and that’s outrageous.

EW: Wow, it’s just like Turkey.

SO: Yeah. But even when we showed it in New York… New York is a very different city. Also then it was in transit, on its side, and very close to the street. And when you were standing up, the total height of the statue, even though it’s massive, it’s not much taller than you are. From that perspective you can connect with it, you can have a different kind of relationship to it, to that object. And in my understanding, this masterpiece of Western art is tipped over. It’s like saying “Fuck you” to the whole art discourse of our civilization.

I do like the situation of it being tipped on its side. Like it’s fallen. And also being brought somewhere. In transit. I like to call it ‘in transit.’

EW: Why do you like this idea of it being in transit so much?

SO: Well… it’s not that I like it so much. It’s that I’m drawn to it… When I’m taking a flight, when you’re checking in, you see a few people, and then once you’re in the cabin you sometimes see the same people, and then during the flight you see them again. And then you land, and you’re waiting for your luggage, you see them again. And every time—I’m sure this happens to me too—every time I look at these people, I almost see somebody different. People change so much during that journey of a few hours. Sometimes people are cheerful in their own country and they’re going on a vacation or to visit somebody. And so when they land they are not in their territory anymore and they look so much different and so much less at ease with themselves. So ‘in transit’ is this very vulnerable existential state, I think.

So it’s a nice deconstruction of this certain masterpiece which is always at home, always at ease, always in the history books, never thought of—never even being perceived as an artwork that we could criticize. It’s always accepted, as I always say, we just accept these artworks as we do the mountains and the sea and the sun and the moon and so on. There’s no critical distance any more between us and them. We don’t think of the moon as not being white enough. It’s just the moon, you just look at it and make sense of it. It’s the same for these masterpieces. So it’s nice to see that masterpiece away from home, in transit.

Ozkaya's "David (inspired by Michelangelo)" installed outside the 21c Museum Hotel, Louisville, KY. Source: The Voice-Tribune.

EW: So tell me about the pasta project that you’re working on.

SO: Last year a friend had asked me to curate a show at her gallery, and one of my ideas was to show maybe fifty or a hundred types of pasta as design objects. Fusilli, spaghetti, whatever, they are designed objects. And show them as artworks, anonymous artworks, and that would be my curatorial project. It never happened, my friend left the gallery, so the dialogue didn’t continue on that path.

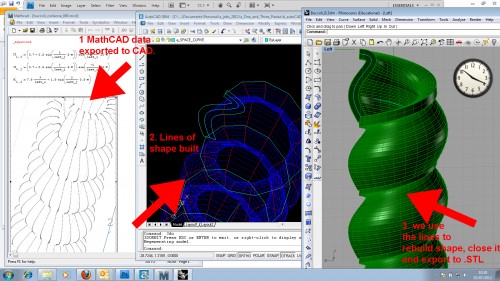

But after that I saw this book, this amazing book by George Legendre, it’s called Pasta By Design, and it’s basically the same idea, the same impulse. He’s a mathematician and professor of design at Harvard, and he took ninety-two types of pasta and he wrote the mathematical formulas for all these types of pasta. As if they were design projects, deliberate designs. In my understanding, he reversed the process, turning this anonymous progress of this object into a design process. I thought that was brilliant. As it turned out he was a close friend of Spyros Papapetros (the guy who was at my talk at Storefront), so we got together. He invited me to Harvard, for some reviews of his students’ work, and we started working on this project. My idea was that since we have the formulas for these objects, we could turn the formulas into computer models, three-dimensional computer models, just like the one I did with David, and print out three-dimensional models or replicas of these things. But pasta is such an organic form, that it always differs from one pasta to another. You know you take two fusilli, and when you take a closer look, they actually differ. They come from the same mold, or the same machine, but they are still organic.

So in my understanding he reversed that process. He went to the ideal of the pasta, the ideal of that particular form, that’s a minuscule object, and I thought it was so fascinating, and so close to my idea. So I thought we could actually print out the computer models, like sculptures, like replicas of these things, but they would actually not be replicas, they would be ideal forms of that particular type of pasta.

EW: Okay. So you’re creating the Platonic ideal of pasta.

SO: Yes. So you know Josef Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs? This project is called One and Three Pasta. We are in the course of making the models right now. What you are going to see in the show is the specimen of a real kind of pasta, a computer generated model or replica of a pasta, which as you were saying is almost as close as you can get to the ideal [of the pasta], and the formula of it. So it’s One and Three Pasta.

And another thing is that when you think of the David sculpture, my fascination with it came from the idea that it was the most valuable man-made object in the world. We know who made it, and from my understanding, it’s the most valuable object in the world. It’s priceless. And it’s not a natural phenomenon, like a big diamond, and it’s not a mystical object, like the vest of the prophet Mohammad or something, but it’s handmade, it’s a deliberately-made, designed and sculpted object by somebody. So when you look at a fusilli, you can buy a pack of them for a dollar. So one fusilli is worth less than a penny. And if you look at it as an edition, as an artwork, and you divide that penny among all the fusilli in the world, it is almost worthless in monetary value. But it possesses a certain design value and nutritious value. So that is also my fascination with it. It is the least valuable art object in the world. So that’s what I want to make an artwork out of it, almost this absurd obsession with this almost but not quite worthless object.

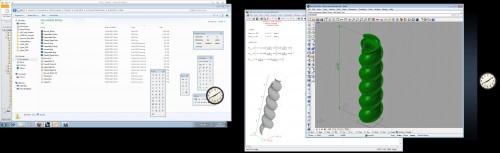

So we are in the course of manufacturing these pieces. George’s staff in London is working on translating the formulas into the necessary computer language, so once that’s finished we can start printing them out. Hopefully we’ll have it finished for this show at Galerist, in Istanbul, to open on October 15.

EW: So you’re using the same technology that you used to create the three-dimensional model that was used for the David sculpture.

SO: Yep. It’s this same kind of computer file, this .STL format.

EW: So you’re creating the Platonic ideal for ninety-two different types of pasta…. That’s a lot of pasta. But they’re really small, so I guess it won’t take up that much space.

SO: Some of them are really complicated, some of them are really small. One obstacle with the fresh pasta is that we don’t know how to preserve it. Some of them will be dry, but some of them, like ravioli, will have to be fresh, because there’s something inside it. I’m currently working on maquettes for displaying the pastas, but I’m also experimenting with ways of preserving them, like maybe coating them with a kind of polyester. Worse comes to worse, the pasta will be changed every day. Or we can just leave it there to rot.

EW: That could be interesting. You don’t usually think of Platonic ideals as rotting.

SO: Yeah. Yeah. So the ideal stays, the computer model stays. But the actual object rots.