The temperature in Chicago was cool for a mid-August day when I drove back into the city on I-90 last week, eagerly anticipating my first glimpse of the unmistakable skyline. My internship at the National Gallery of Art complete, my goodbyes to D.C. and its residents delivered, I was ready to celebrate my return with some lazy afternoons on the shore of Lake Michigan.

Google image search results for "Chicago skyline from I-90," from www.fineartphotographybyniraj.com.

Of course, lounging lakeside is less fun with the task of finding a “real job” hanging over one’s head. But before I fully resign myself to trolling career sites for postings and creating endless variations on my resume, I want to talk about my summer.

Some of the most unexpected pleasures of my internship were the twice-weekly morning seminars, in which we (fifteen or so recent grads and current grad students) met with an employee in each of the Gallery’s major departments. In addition to giving us the chance to hear from museum professionals about their career paths and learn about everything from lighting to horticulture to object conservation, these talks allowed us to glimpse the connections between departments and to understand where and how internal collaboration occurs.

I will never get tired of studying how museums work. Every once in a while, I walk into one and think that it would be nice to only care about the art, and not the hundreds of tiny decisions that went into determining its display. Then the moment passes, and I remember this: the meta matters.

Not every museum visitor needs or wants to know why some sculptures are on pedestals and some are in vitrines, who writes the wall text, or what the institution’s collections policy is. But I strongly believe that this information should be available to anyone who desires it, and that all visitors should have an idea of the kinds of decisions museum workers regularly make that directly affect their viewing experience.

The more factors you know of that impact the display of an object in the museum, the more access points you have to that object. Even the most cryptic or seemingly uninteresting work of art can come to life as you begin to question the steps that brought it to where it resides. One example that comes to mind is something I got to spend a good deal of time with this summer, a work by the contemporary British artist Idris Khan.

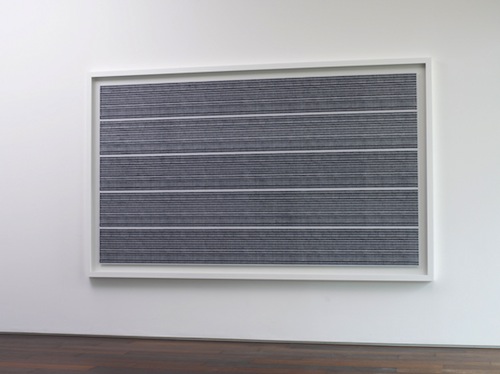

Tucked away in an elevator lobby between the East and West Buildings and out of the direct line of sight of the average visitor, The Creation comes off much as it does in the above photo: an excessively large, gray-black rectangle punctuated by white striations. What is it made of? What does it represent? And why is it in the National Gallery?

Stepping into the lobby and approaching the work reveals several things: marks and lines that suggest musical notes, a label identifying it as a chromogenic print from 2009, another work by the same artist on the adjacent wall, and a didactic text to accompany the pair. As you learn more about The Creation, other questions arise. If it is technically a photograph, why isn’t it in the photography galleries? Why does it merit a wall text when little else in the permanent collection does? What is the significance of hanging this in what functions as a transition space in the museum?

These are the sorts of questions that, for me, unlock meanings of a work of art. Not all objects in museums speak to me, aesthetically or intellectually, but almost all of them intrigue me. In addition to the stories of their conception and execution by the artists that made them, they carry the stories of how they came to be prized and varied, of the context that someone decided to place them in, and of the associations that people who look at them everyday make with their surroundings and the outside world.

At the beginning of August, I attended a program during which a performer read a poem by Lisel Mueller called Monet Refuses the Operation. In the poem, Mueller imagines the Impressionist’s reaction to the suggestion that he undergo cataract surgery. She writes: “What can I say to convince you/the Houses of Parliament dissolve/night after night to become/the fluid dream of the Thames?/I will not return to a universe/of objects that don’t know each other,/as if islands were not the lost children of one great continent.”

It is a beautiful and stirring poem, but that line about refusing to return to a universe of objects that don’t know each other evokes a more whimsical image in my mind: the Disney movie Toy Story, in which a child’s playthings come to life when humans leave the room.

This is how I like to imagine artworks in museums: conversing with each other at the end of every day, trading stories about visitors’ comments and reactions, and discovering their hidden commonalities. It is learning about how museums work and what the people who work in them do that feeds this fantasy. Although I don’t know exactly where my future career path will take me, I hope it entails introducing more people to the Toy Story view of the art museum.