Doug Ashford. "Six Moments in 1967 #5," 2011. Tempera and inkjet on wood. 30.5 cm sq. Courtesy Doug Ashford.

Doug Ashford is widely known for his work with the New York City-based artist group, Group Material, from 1983-1996. Through this sustained collaboration Ashford and his peers pioneered forms of installation and curation that explored radical modes of participation and historical representation. The work of Group Material also attempted to inform the public of the US’s tragic role in geopolitics (through works like Timeline: A Chronicle of US Intervention in Central and Latin America, 1984), and to intervene in public political discourse (as in their work Democracy: AIDS and Democracy: A Case Study, 1988-89 and other exhibitions critical of US foreign and domestic policies).

What comes after Group Material seems to me in keeping with Ashford’s aesthetic and political preoccupations. Since his participation in the group, he has worked as a professor at Cooper Union where he has cultivated an environment of collaborative effort among students and with his fellow faculty members. Attending his Friday night seminar in the winter of 2010 on a night when the poet-critical theorist Fred Moten was visiting, I appreciated the specific duration of the seminar, where he did not hesitate to have his students meet on the busiest social night of the week, nor extend discussion well into the night (the seminar began around 6pm and didn’t end until 10 or 11).

What has also been clear to me in Ashford’s transition from Group Material to an “individual” practice (I hesitate to use this word, given Ashford’s demonstrated commitments to participation and collaboration), is his emphasis on ways that affect shapes our lives as subjects and forms a basis for collective struggle. This is clear in the multiple interviews he has given in the past decade and in his writings and talks, where a subtle attention to affect and empathy allows him to reflect upon various social potentialities during a particularly dark moment in our history.

Ashford’s understanding of the role of affect in aesthetic politics has developed concurrently with an exploration of abstract painting, which he discusses below. While his recourse to abstraction could easily be seen as a move into a more conservative position towards his art practice, a flight into interiority and “art for art’s sake,” Ashford understands abstraction as a site where feeling can become activated towards individual, interpersonal, and collective transformations. Inasmuch as Ashford’s abstract paintings form environments (they are often installed together upon gallery walls or within an enclosed structure, such as in Many Readers of One Event at Documenta 13 [2012]), and include documentary images depicting political and social upheaval (such as in Six Moments in 1967 #5, 2011 above), they seek to wield color abstraction as a force coincident with social movement—affects, gestures, bodies.

1. What is your background as an artist and how does this background inform and motivate your practice?

My mother was an unknown still-life painter, an amateur perhaps. In my imagination she was hoping to see a way through the confines of the domestic maternal life of the 1960’s towards the freedom offered in artistic depiction. This private labor had a big impact on me by lighting up the frustrations art simultaneously creates and relieves for a life limited by circumstances. She also was active in the civil, housing and mental health rights movements: a Saturday demonstrator and a Sunday painter. Although she lamented the world’s cruelty often, she spoke to me mostly about how justice might be forseen in beautiful things. And although never articulated, the difficulty of this proposition was something I am sure we had an agreement on, conscious or not. As a consequence, I began to make and defend artworks as things that might change the world relatively early on in life.

Doug Ashford. "Many Readers of One Event," 2012, (detail). Tempera and inkjet on wood. Dimensions variable. Installed for dOCUMENTA 13, Museum Fridericianum and other locations, Kassel, Germany. Courtesy Doug Ashford.

Although I was always teaching and making pictures through the 80’s and 90’s, my principle circulated practice as a younger artist was the collaborative work I did as a member of Group Material (1983-96). Group Material’s proclamation of an ongoing re-design of art’s relationship to life meant that audiences could be placed into positions of social identification though art works. For us the exhibition could become a template for the forum, the parliament, and the agora: repeated examples of ongoing conversation that contested the terrain of political life. To achieve this larger rapport, we depended on extended collaborations with many others – both artists and not – to emphasize the value of dissensus and comparison in determining the values produced by culture. By including objects that challenged the existing propositions of the museum, we suggested an overhaul of the habits of authorship, and an altering of the social histories that art might imply. The resulting ensemble was then physically designed to position a viewer at an apex of productive confusion, juxtaposition and comparison – making visible the possibility of a dialogic form that tried to designate both the complexity of political work and the oceanic possibility of aesthetic play.

Doug Ashford. "Many Readers of One Event," 2012. Tempera and inkjet on wood. Dimensions variable. Installed for dOCUMENTA 13, Museum Fridericianum and other locations, Kassel, Germany. Courtesy Doug Ashford.

2. Do you feel there is a need for the work that you are doing given the larger field of visual art and the ways that aesthetic practices may be able to shape public space, civic responsibility, and political action? Why or why not?

Reconstructing the space of the museum, the histories of art, and the political imaginary into new shapes and forms continued to occupy me as I went on to work in venues for social practice alone and in new collaborations after Group Material disbanded. But increasingly the recognizable hopes that I have for life, for love and affinity continue beyond the organizational space for art and politics – suggesting a struggle that doesn’t end at the lobby, that is harder to see, a phantom or mirage that follows me around. For now, this featureless figure seems best thought over through the production of painted images.

I find the wreckage upon wreckage that constitutes the present almost unbearable. But in functioning less well these days, perhaps I am not alone. Discontinuation, withdrawal, un-acceptance, retreat, and the rejection of consensus that anti-institutional intimacies imply today seem to provide a radical energy to a possible politics. I recognize the abstract programs and instruments of an earlier and ideal modernity (and its coincident art) as factors in the degradation of the radical sense of humanity I grew up with. Is it then useless to imagine social participation in an abstract way? If democracy is the abstract empty space for discourse and creative agonism, how do we visualize its effects, its production, and its dreams? The forms in my working process these days are chosen for both their factual reportage and their imagistic drift. I want to know what motivates the figures depicted, if they imagine in unknown relations; figures that are beautiful because they respond to emergency, moving as if empathy has taken them into a momentum that overcomes catastrophe. Although sometimes hard to see, political disaster creates events of extraordinary love because it makes the enduring of life imaginable beyond dark practical economies of getting and selling.

The Parade, a series of solutions by Cooper Union School of Art first year art students to assignments questioning public space; Doug Ashford, Robert Boyd, and Pam Lins, instructors. 1998. Courtesy Doug Ashford.

3. Are there other projects, people, and/or things that have inspired your work? Please describe.

In a certain measure I have been a teacher for as long as I have made pictures. The practice of the classroom is always an extended collaboration into the values and dreams of others. But bringing up this work here I do not mean to make the goals of education and art equivalent; however imaginatively related they may be. I have recently tried to distance myself from the promotion of “school as art” fearing the equation disavows the concrete problems of education today: privatization, abusive labor practices, elitist class re-enfranchisement, etc. On the other hand, I have to admit that the classroom follows me into the studio every day I am there – more perhaps than the normative professionalizing phantasm of this working the other way around.

Safety. An exhibition by the Cooper Union School of Art class “Shifting Territories: Censorship in Modern Society.” Doug Ashford and Catherine Siemann, instructors. 2006. Courtesy Doug Ashford.

One important reminder of the classroom is that we are all potentially more than our circumstances (the teacher too!). I want to unmake the expectations of expertise, ignore the proscenium, and disavow the knowledge that I might bring to the room. This is obviously a very awkward proposal but means that a neurotic need can be invented in line with what students want as a temporary platform, a labor-act existing only under the particular terms of propositions and responses and more propositions. These days I am much more invested in an idea of such performed partnerships: just as the artwork I make now takes a great deal of time sitting alone in a room acting out – talking to people who are no longer here.

Group Material. "The Castle," 1987, installed for documenta 8, Museum Fridericianum, Kassel, Germany. Courtesy Doug Ashford.

4. What have been your favorite projects to work on and why?

A simple experiment for me these days is to see how the documents of social engagement I perform, collect and remember can be re–imagined as shapes and colors. It’s like playing a substitution game between memory and form. Sometimes the immersive experiences of abstract shapes can reposition the psychological and political reactions I have to documented history into distinctly new feelings; disunited from the context of rational progress and shifted into associated affect. I am still unsure of the results when working beyond the capacity of thesis and essay. I worry that this may just be an empirical gesture or a recuperative project where the past can take the place of present actors, a palliative tableau that mixes therapeutically with social expectations. But by painting “against” a document, the cruelties of facts take on multiple stories in distorted recognition with expectations. And this is very pleasurable.

On a more anthropological level, this kind of intellectual freefall seems only able to take precedence when its formal configurations, its outline or impression, can be perceived as repeated entities. Perhaps this is like a daemonic possession or a ritualized occupation in the animistic sense (“they visit me every night”). To be possessed by an image might mean to be offered the chance to be other than the “human” the world has already defined in me. But I don’t mean to make it so grandiose. This sounds too large for what I am actually doing – making small abstract pictures.

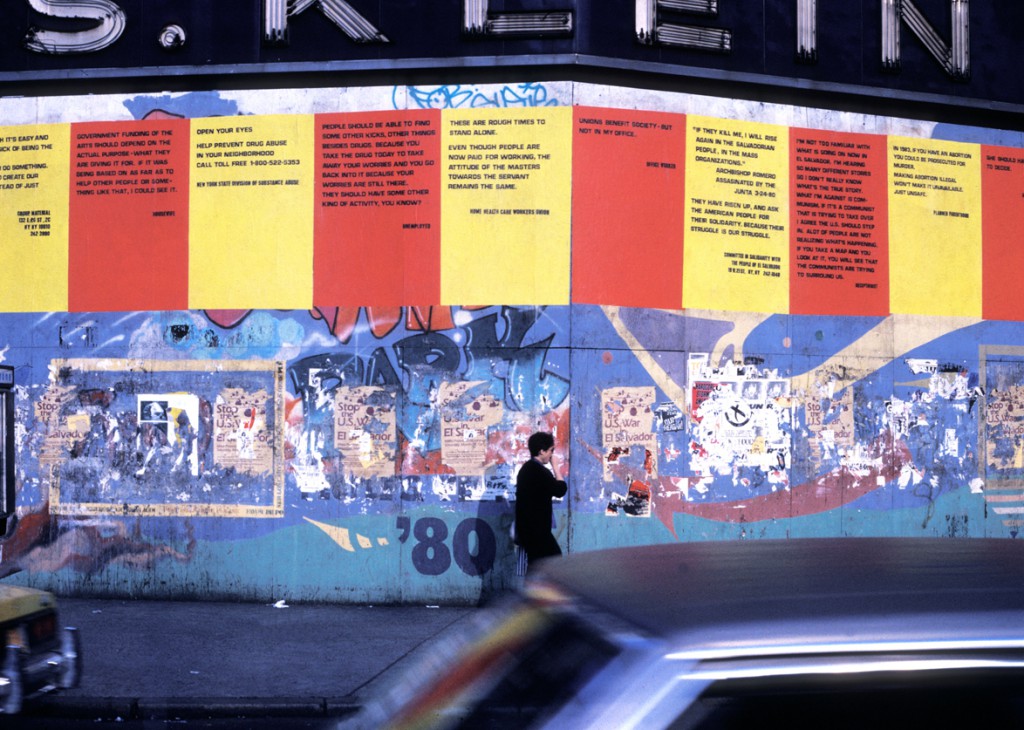

Group Material. "DA ZI BAOS," 1982. Installed on April 16th at the former S. Klein Building, 14th Street and Park Avenue South, New York. Courtesy Doug Ashford.

5. What projects would you like to work on in the future? What directions do you imagine taking your work in?

This would be a more theatrical context of design, where pictures can take the place of people, a tableau vivant of social mediation. By positioning paintings against documents and bodies, I’m wondering what it means to look away, or to look backwards at reality as if betrayed, allowing the facts in a photograph to take on new recognitions.

This theatre would be designed into a room where the division between agency (what I can do) and effect (what is done to me) would appear to dissolve into relationships between colors and shapes. There is a huge reservoir of feeling produced by abstraction, daily in the dark impartiality of economic systems that tear our cultures apart – and more rarely as the brighter possibilities of a distanced view. Both are positions of looking (and thinking and making) and both are incandescent in the separation that shines from them as they leave spaces of reality. This room would propose a place between the dark abstractions of normality and the bright ones of our aspirations, suggesting the failures of life lit up.