The inspiration for this column came from conversations with artists about how ideas develop into finished work. It’s something that has always fascinated me as a fiction writer. The process of making art seems almost alchemical, drawing from yet exceeding our personal history, as there are traces of the transmutation in it, that agent of the unknown, all that’s otherworldly and unpredictable about creating.

As for the known properties, they are often incredibly specific to our lives, the situations and secrets, worries, the people we’ve loved. Preoccupations and details, from the mundane to the exalted. These are, as Louise Bourgeois has it, the stray portions of our consciousness that coalesce into a creative work. As such, we’re typically both authorities and alarmingly ignorant about what’s going on there.

But the human element is often more enormously complex than the few defining details on the wall panel would indicate. In that sense, I hope for this column to be exploratory, interviewing and reviewing, looking at the lives and multiple sources of inspiration for iconic, established, and emerging artists. While acknowledging that art will always exist outside the system of signs and signifiers that we use to navigate the world.

I’ll begin with one of the most talked-about shows in New York this summer—the Yayoi Kusama retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, closing at the end of the month. The Japanese artist, born in 1929, arrived in New York in 1958, where she became part of the ’60s avant-garde, Donald Judd, Warhol, Claes Oldenburg. She was best known at the time for her naked “body festivals,” which included a lot of ’60s-style orgiastic touching and skin painting in public places. Very much a cultural phenomenon, with many enthusiastic participants, that looks as if it were far more interesting in person than archivally.

The exhibition itself, though, seems framed not by this salacious history, but something even more provocative—for the past thirty years Kusama has been living in a mental hospital in Japan—she does most of her work offsite, in a studio across the road. Her illness is the most lurid detail on the wall panel, and the installation decisions magnify the sense of mental claustrophobia in the work, the rapid, unchecked multiplication of an obsessive mind, and one inhabited by fear. In the show’s final room, the most recent work, a replicating series of tiny faces, eyeglasses, teacups, and footed shoes, sinisterly decontextualized, march across hysterically bright canvases. The outsized paintings are stacked two to three deep, floor to ceiling, so that we, too, are walled in by them. Then we exit to the elevator.

Kusama readily associates her art with her illness, calling it, in an interview with Bomb, an expression not only of her life, but “particularly of [her] mental disease.” She began having hallucinations at the age of ten. That’s also when she began painting them.

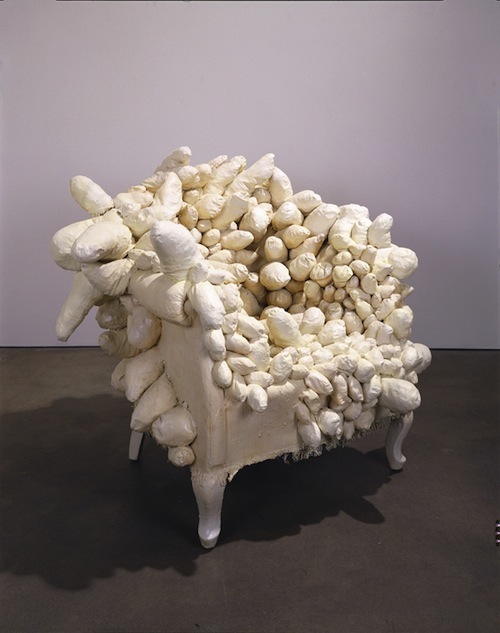

The Sex Obsession and Accumulation series of the mid-60s, some of her most famous work, stems from a sex-fear vision. Composed of the most un-phallic phalluses, these are little warty, benign protuberances that in their sheer proliferation, and stubbornness, become terrifying. They hang off the shoulders of her dress, grow out of her shoes, and handbag. They’re in the kitchen, all over the cooking utensils, on the furniture. As personal as this nightmarish vision is, it may have also sprung from a lived reality. At the time Kusama was fighting to make a name for herself in a Pop Art movement dominated by male artists who would alternately assist, overshadow, obsess over her (see below), and sometimes rip-off her style (Oldenburg, according to Kusama, developed his monumental soft-sculpture work after showing with her at the Green Gallery in ‘62).

Yayoi Kusama (b. 1929). Accumulation, c. 1963. Sewn and stuffed fabric, wood chair frame, paint, 35 1/2 x 38 1/2 x 35 in. (90.2 x 97.8 x 88.9 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase 2001.342. © Yayoi Kusama. Photograph by Tom Powel.

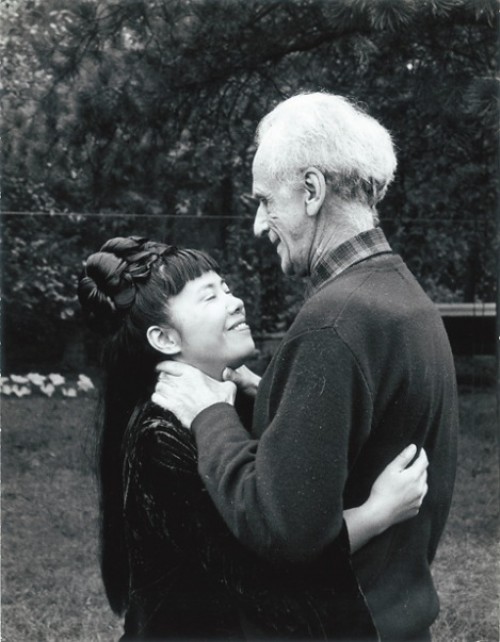

If the illness does threaten to be a defining inspiration, it is also, in truth, what she’s always made to talk about in interviews. The question is asked and Kusama answers it, offering the internal explanation for an outwardly lived life. Which is why one of the most touching, and telling, parts of the exhibition is the biographical room of letters and clippings and notes, where her obsessive disorder doesn’t seem to have much of a foothold compared to everything else. The standouts there are two charming and intriguing black-and-white photographs of Kusama (looking very lovely) with her once-boyfriend, twenty-five years her senior, artist Joseph Cornell. Cornell, the odd-duck, the loner who lived with his domineering mother in Flushing, Queens, and who spent his days, too many, bickering with her and waiting for the mailman to come. And dreaming—of romance, vanished European cities, long-dead ballerinas. He channeled all that longing into his boxes, creating intricate little worlds the dimensions of thoughts.

Around 1964, Cornell, himself sixty, was looking to try sketching from a live model. The thirty-five-year-old Kusama, an admirer of his, was sent over to pose. There is a strong possibility that this was the first time Cornell had ever seen a naked woman. As Deborah Solomon notes in her biography, the sketches he did that day look as if his hand “was trembling.”

According to Kusama, it was love at first sight for Cornell. But this sort of thing really didn’t bring out his best self, largely because he could never take it to the level of a relationship, or even sex, which he feared more than she did. A passionate passive, a suitor with no end game, he had all the relentless ardor of someone used to taking it to the next level in his own head. He began tying up the phone line, setting ablaze the mails. On one day he sent her thirteen letters. He successfully set up a barricade of attentions so that “I was just not able to make any other boyfriend,” Kusama said. She wasn’t all that keen on being on the receiving end of someone else’s obsessive behavior. After a while, she says, “I was dying to break it off with him.”

But with Kusama, Cornell would experience his first kiss, touch a woman’s body for the first time, as well as a few other things. Experiences so intensely and gratifyingly sensual, he could only ever talk about them in French. Kusama’s accounts are far less rhapsodic and reveal a lot of frustration. So, was the famous Cornell more of a mentor, an influence on her collage work of the 1970s? He may have been many things to her, but not that. Kusama actually attributes the influence on collage to flow in the other direction.

This says a lot about her. For all the pathologizing of her source of inspiration, the hallucinations that have plagued her, Kusama was also an incredibly determined and willful and courageous young artist. In her twenties, unknown, she wrote Georgia O’Keeffe a letter from Japan and, after receiving a not-so-encouraging reply, showed up anyway. She did this with little English, even less money, and no support, material or emotional—her horrendously abusive mother used to tear up her paintings. But what overrides the torment in the artwork is pleasure, a sort of visual exuberance, and the tenacity of its creator, who was looking to overturn the American idea of “Japanese girls as delicate hot-house flowers.” Even with all her private turmoil, more than forty years before this Whitney retrospective, Kusama understood herself to be a “human dynamo of creative energy and artistic achievement.”

I welcome thoughts, ideas, show announcements. Please email me at [email protected].

NOTES

Louise Bourgeois, Louise Bourgeois: Drawings and Observations (New York: Little, Brown, 1995).

Yayoi Kusama, interview by Grady Turner, Bomb 66 (winter 1999).

I’m very indebted to Deborah Solomon’s fascinating biography on Cornell, Utopia Parkway: The Life and Work of Joseph Cornell (New York: FSG, 1997) for the anecdotes above.