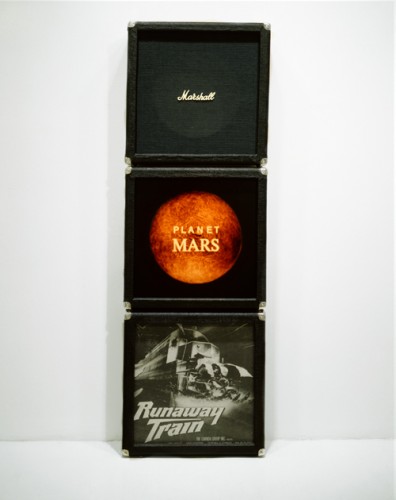

Jennifer Bolande. “Marshall Stack,” 1987. Three handmade vinyl and wood speaker cabinets, color photos, Marshall speaker cloth, plastic Marshall logo. Photo by Eeva Inkeri.

Last Friday, Los Angeles enthusiastically welcomed the space shuttle Endeavour as it made its final journey through the sky on the back of a Boeing Jet, after showing off on a cross-country journey and finally landing at LAX. But the patriotism and cheers meeting Endeavour as it made its way toward its new home at the California Science Center—in a city starved for monuments—seemed to mask the melancholy surrounding the waning of NASA. The space shuttle, which was supposed to be the final mission in the NASA space shuttle program (though Atlantis ultimately took that title) simultaneously embodies triumph and defeat. Our space program developed as a means to flex the muscles of capitalism and American might against communism and the iron curtain. Now, decades later, in the face of economic catastrophe, we see laissez-faire capitalism failing nearly as dramatically as communism did, and our priveleged place in the international pecking order slipping away.

Endeavour flying over the Hollywood Sign. Courtesy Reuters.

On the same day as Endeavor’s arrival, Jennifer Bolande’s survey exhibition Landmarks opened at Cal State Los Angeles’ Luckman Gallery, having previously traveled from Milwaukee to Philadelphia. Employing the same title as her debut exhibition, the idea of landmarks pervades Bolande’s photographs and sculptural installations. Long before settling in Los Angeles, Bolande began engaging with physical manifestations of cinema, mass media and technology.

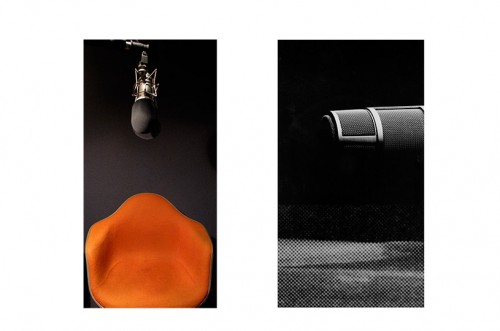

Her engagement with specific kinds of machines—big speakers, old-fashioned microphones, spotlights, and even printed photographs themselves—tend to point to bygone eras, while resisting nostalgia. Rather than idealizing, celebrating, or mourning the past, Bolande’s works displace the objects depicted, destabilizing their relationship to time and place. In part, she transcends this trite reading by pairing these man-made machines with (equally dated) didactic emblems of nature and scientific exploration—globes, mountains, and photos of distant planets repeat throughout many works. Thus, Bolande’s work seems to point not to isolated eras of the past, but to our ongoing struggle to understand our place in the natural world through the constantly evolving technology of representation.

Jennifer Bolande. “Diptych #3,” from the series Space Photography, 2009. Courtesy of the artist.

I misread the announcement for Landmarks; as I was rushing through the empty Cal State LA I discovered that I had missed the opening reception by 24 hours. The gallery happened to be unlocked at 9 pm on a Saturday night because of a performance in the adjacent theater, which made for a wholly uncanny experience. Scurrying into a space expecting it to be full of bodies and finding it completely empty felt like wandering into the twilight zone—but it also seemed like the perfect way to experience Bolande’s work. From the bodiless chairs in Space Photography, to the headless bust in The Rounding of Corners, to the empty laundry rooms in Appliance Contact, each of Bolande’s objects swell with a pregnant lack of the human body.

Jennifer Bolande. “Movie Chair,” 1984. Wooden chair, velvet, bronze, enamel paint, light stands, lights, gaffer’s tape. Courtesy of the artist.

Though this emptiness references isolation, the sense of a void implicates the viewer in each work, rather than pushes the viewer away. Landmarks positions its mechanical elements as fertile emblems of transition and liminality instead of nostalgic shells of historical moments. Thus, Bolande manages to bring dynamism and warmth where one might expect to find melancholy and coldness. Next month, Endeavour will travel across the streets of Los Angeles to its final home at the California Science Center. As a city conspicuously devoid of grand landmarks, having favored cultural production over public space, Los Angeles seems thrilled with its new monument to space travel. Like Endeavour, the iconic machines explored by Bolande embody not just a historical moment, but remain animated as representations of transition and transformation.