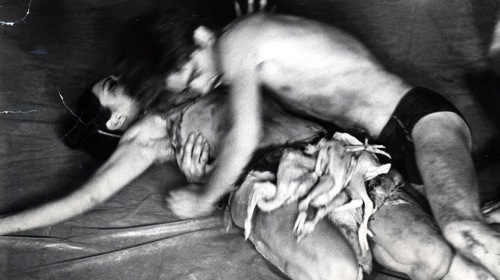

Carolee Schneemann performing “Meat Joy” at Judson Dance Theater, 1964. Image credit: Al Giese.

This post is a recap, highlighting events so far this fall that have captured my attention. Unfortunately, in the hustle of being a working artist, my reflections get filed away during commutes and in spurts of studio time. At the same time, I have been immersed in reading, talking and thinking about the history and legacy of Judson Dance Theater (JDT) in the 50th Anniversary of its collaborative creation. I found myself writing an extended essay on the subject in relationship to both activism and gender politics. While it awaits publication, its themes have woven their way into my perspective when viewing performance lately. It seems many kinds of performance practices can be seen to be in dialogue with JDT, or its wake. Not that the work has to be wholly reflective of those occurrences in the 1960’s, but a strand of something comes through and lights up a picture of performance now.

Relating to this history is a sense of place that I have been re-experiencing since returning to New York after a five year absence. It might not seem like much, but in that time, entirely new generations have taken up residency in different neighborhoods–populating, gentrifying, re-combining, and creating entirely new topographies than those I had previously known. The focus of this post is on work that I have seen in Brooklyn.

Rob Fischer. “Ten Yards,” 2003. Mixed media, 54 x 174 x80 in. The window of my studio looked over Fischer’s studio on Varet St. at the time when this piece was exhibited in the 2004 Whitney Biennial. Image Credit: thecityreview.com.

There is something to be said of the juxtaposition of history and place in thinking about where forms originate, in what communities, and how these communities are established. In 1962, Judson Memorial Church in Greenwich Village was home to a diverse array of artists the way (remaining) loft spaces and studios in Brooklyn operate now. Once, I lived as a poet at such a loft among choreographers, composers, visual artists, and aspiring yogis. Since then, however, the building has become a luxury loft youth hostel.

The site of Fischer’s old studio, now a courtyard for the New York Loft Youth Hostel. I lived up on the second balcony (there was no balcony whirlpool). Image credit: hotelsclub.com.

Here I am, perambulating around this place imbued with memories, a former sense of belonging to a world of artists who have since become more itinerant, or who have relocated to Europe with the promise of a more fluid lifestyle and a better chance at funding. The feeling of being new is both thrilling and terrifying, especially when memories of a bohemian past clash wildly with a privileged present (illustrated by the contrasting images above). For some artists, living in New York means finding a means to brand themselves in the pursuit of fame and fortune, and for others, living here means having the freedom to be an artist, perhaps not through fortune but by simply making something can be seen and appreciated by others. There is a market. There are many communities. Sometimes we move up, and sometimes we move through. I find this point highly reflective of Judson Dance Theater, where artists were looking to experiment with one another for their own aesthetic goals and desires. Some performances became blockbusters, others stayed local, and some performers are reaching the height of their careers fifty years later. Now that’s an enduring artistic practice!

Katy Pyle and Jules Skloot performing “Covers” at the Bushwick Starr. Image credit: Christy Pessagno.

Let the log of Brooklyn performances begin:

On September 7, I went to the Bushwick Starr, a studio founded in 2001 that developed into a theater in 2007. I went to see the “propeller project” by Katy Pyle and Jules Skloot, an evening-length performance of Covers. I had gender and performance on the brain, after exploring a comparison of performances by JDT artists Carolee Schneemann and Yvonne Rainer. I was thinking about how each artist confronted “the gaze”– the expectant gaze of the audience–the “male gaze,” or the permitted inheritance of scopophilia. This performance intersected with my concerns as the performers spent most of the first half of the performance under quilts. What better way to present a performance confronting gender identity than to remain hidden? It reminds me of my previous Art21 blog post, “No Future,” where I discussed Miranda July’s t-shirt dance in The Future and the imagery of “hiddenness.”

Lucinda Childs re-performing “Pastime” from 1963 at Danspace Project, Sept. 17 2012, for its Judson Now Platform. Image credit: Ian Douglas.

While Pyle and Skloot briefly reveal the lower half of their naked bodies under their quilts, they change into a series of costumes throughout the piece that never completely reveal their “real” bodies. Their campy mermaid and sailor number, or their duet in coveralls and sunglasses, play with performing roles–femme-butch roles, the veneer of hetero and homo normative roles, and the performance of fantasy in pop and rock ballads. Each of the “covers” calls greater attention to an image that can never be attained than to the perfection of that image, as the choreography and music outlandishly exploit sentimentality for conventional roles and conventional desire. At the end of the piece, after Pyle and Skloot have a back-and-forth dialogue of phrases that start with, “I thought you were…,” Pyle says she always wanted to have a party with an invitation that would read:

To all the adults who will never grow up and will never be allowed to, to all the boys whose mothers walked in on them kissing the bathroom mirror, to all the girls who lost themselves in baggy clothes, to all the children who threw up in the locker room, to those who wake up differently every morning, to those who are pressured to choose, to those who left home early but whose homes won’t leave them alone…to those who stuff and who bind, and to those who strive for connection, protection, submission and domination, consummation, and liberation, please come dressed as yourself.

Pyle, left and Skloot, right, singing after a dialogue inside of a fort made of blankets. Quilts in the background made by Pyle. Image credit: Christy Pessagno.

The text, written by Francis Rabkin for Pyle and Skloot, speaks to this “thing”–this event, movement, or object called queerness that is its own emergent context. We’re at a threshold of the queering of everything, but it is thankfully far from the derogative meaning of queer during the early 1960’s. Gender expression was paleolithic at that time, confronting the audience with the fact of the body, and deconstructing virtuosity took the place of a dialogue about identity. These issues intersect and diverge at different points, but the search for autonomy of the body and the denial of fixed meanings of identity are part of the legacy of JDT. Schneemann directed Meat Joy with men and women raucously dancing with loin cloths and old meat, while Rainer denied the spectacle completely, dancing at angles that subverted a fixed idea of her body. Now we’re dancing and performing in the legacy of these choices, making our own, and opting for them all.

Michael Paul Britto. Video still from “Free Dem,” 2011. Image courtesy the artist.

On Septmeber 9, I went to the NARS Foundation for GO Brooklyn open studios. I didn’t actually participate in the voting part of the competition because I’m more interested in supporting my friends than choosing who the best artist is among them. I personally don’t see the need for another new competitive arena in the art world, after Work of Art, Gallery Girls, whatever. It’s almost like the curators got everyone and their friends to do the leg work for them! Having said this, I am happy to have met Michael Paul Britto at NARS. I was struck by his collage, video and performance work critiquing and parodying popularized images of Black identity. I was struck by his video “Free Dem,” where he superimposed images of women “slave-dancing” next to one another, so that they are dancing with a ghost-image of the other. Britto stages much of his work that he then uses for video, and works with acting students to create parodies of a menacing history that he then makes more disturbing through a slight change of audio or visuals. “Free Dem,” is a dance video–and a haunting one that asks the viewer whether the past can truly be left behind.

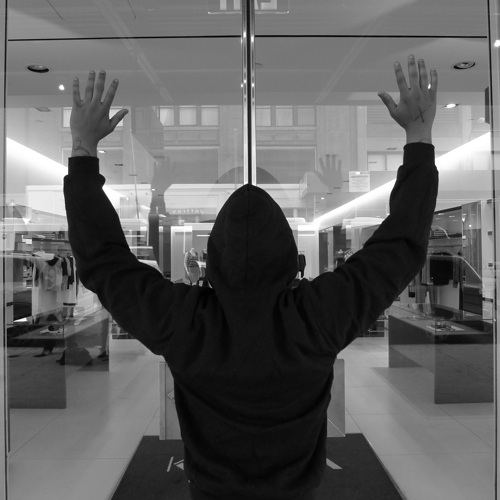

Britto. “The Suspect War.” Image courtesy the artist.

Britto’s latest project is “The Suspect War” for Art In Odd Places Oct 6-7. A “Stop & Frisked” runway for anyone who has been racially profiled, “models” gathered at Krizia in Chelsea to strut the outfit they were wearing when they were stopped. Britto defined appropriate fashion for the event:

Black Hooded Sweatshirt

Black Sweatpants

Red Hooded Sweatshirt

White T-Shirt

Yankees Caps

Jeans

Any Type of Graphic T-Shirt

Sneakers

Work boots

Brown Skin

Tan Skin

Dark Brown Skin

The concept for the piece was generated by Britto after he was stopped and frisked in Chelsea when attending openings earlier this year. When the officer searched his bags and found his camera equipment, he said to Britto, “There’s no reason for someone like you to have all this equipment.” Fortunately, Britto saw opportunity in the worst of circumstances and got the boutique near the location where he was stopped to host his runway. Stay tuned for a further discussion of “The Suspect War,” and more performances in Part 2 of this post.