Objects need not be natural, simple, or indestructible. Instead, objects will be defined by their autonomous reality. –Graham Harman, The Quadruple Object, Zero Books, 2011.

The frame of an installation encloses the maximum number of components in the field. At the same time, the frame creates an image that “opens onto a play of relations which are purely thought and which weave a whole. Therefore, there is always out-of-field, even in the most closed image. — Jungmin Lee, “Modes of Exhibition as Mediated Space: Projection Installation as Spectatorial Frame,” Art&Education.

In this particular frame we find ourselves on the second floor of the Hyde Park Art Center. Light streams through a few windows into a clean, contemporary exhibition space. In the back of the room towards the window, colorful objects rest on folding tables — a bicycle wheel, for instance, a ceramic pumpkin, an umbrella and a life preserver: those objects have been arranged according to their color (orange, pink, white, black etc.) and seem to wait either for a still life drawing class or a curious church sale. In another portion of the room hollow metal cubes (what might have once functioned as store display cases) have been decorated with a variety of objects — a rubber brush, a draped piece of fabric, a mannequin’s hand, a card printed with various kinds of exotic fish — on the one hand these object seem random but given their painstaking placement, they command attention as monuments made with white elephants.

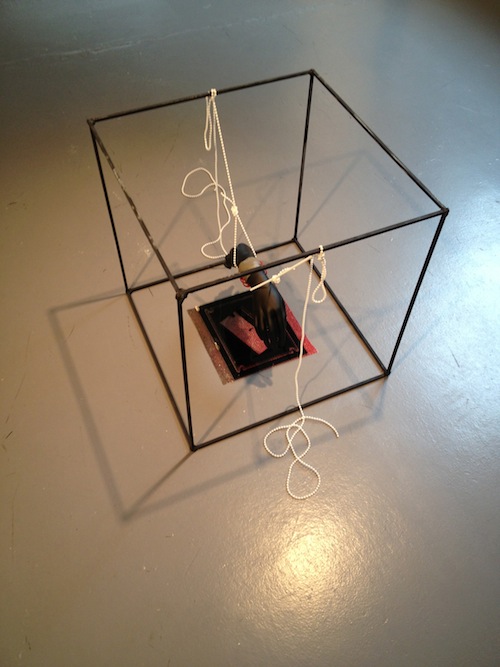

Laura Davis. “Two Histories of the World: Part Two,” 2012. Mixed Media. Hyde Park Art Center. Photo by Caroline Picard.

Small, brightly-colored paintings hang on the wall composed with various layers of green or pink paper, plastic and fabric. The gestural folds of these various mediums intertwine and layer like paint. A video projection streams large on the back wall and across from it, a sound installation loops through a parabolic speaker. Standing beneath the speaker, you hear a collage of voices recounting their experience — it is evidently common because they happen to describe the same phenomena and on several occasions repeat similar phrases. Sometimes the voices run through and on top of one other, sometimes you only hear one speaker alone. The authors of these multi-media works remain obscure at first glance (although an exhibition map is available) and their initial absence enforces the already mysterious character of the objects at hand.

Mara Baker. “Two Histories of the World: Part Two,”2012. Mixed media. Hyde Part Art Center. Photo by Caroline Picard.

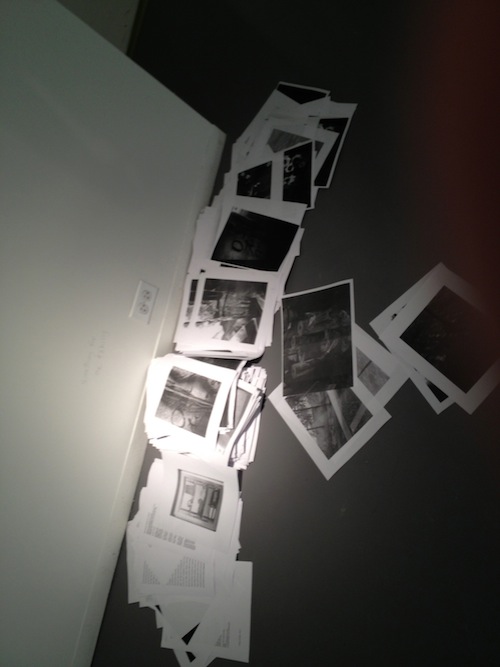

Sara Black and Jillian Soto created the folding table assemblages. The hollow metal cubes were made by Laura Davis. Mara Baker composed each of the four paintings and the video belongs to Mike Schuh. Heather Mekkelson made the sound piece. On the whole they do not fit easily into any category: as sculptures or readymades or basement leftovers. Their resistance seems like a resistance of identity, as though these things possess something larger than what is immediately present. They might contain a static purpose — something imbuing the objects with an interiority not easily accessible. These objects point to their life outside of the Hyde Park Art Center, into a past, dimly-lit warehouse. A scattered pile of Xerox pages lies to the right of the Art Center’s gallery door — these are there for the taking, as supplementary texts. Their seeming chaotic placement is perhaps the most obvious echo of this exhibit’s first iteration. It is, after all, Part Two of Two Histories of the World.

“Two Histories of the World: Part Two.” Supplementary paper materials available to viewers. Installation view, Hyde Park Art Center, 2012. Photo by Caroline Picard.

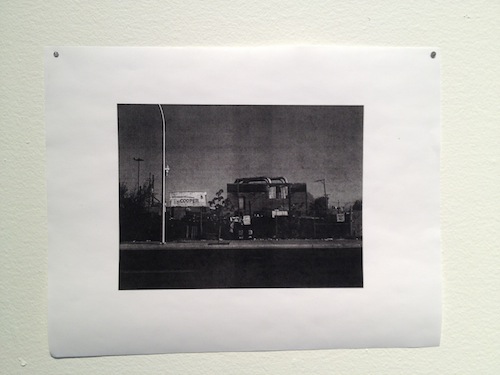

“Two Histories of the World: Part Two.” Xerox image of the William H. Cooper Mfg. on display at Hyde Part Art Center, 2012. Photo by Caroline Picard.

About a year ago five of these seven artists installed Part One of Two Histories of the World in an old resale warehouse, William H. Cooper Mfg., at the behest of curator Karsten Lund. The warehouse was full of everything — just so much stuff, and random stuff at that: trash cans full of never-used (but dusty) shampoo bottles, old refrigerators, a 1983 RV truck, piles of wood and sawdust, never-before-used mirrors from the 1990s, computer parts and cardboard boxes. It was like a warehouse where Things go to die.

The building itself was immense and exceptionally dirty. Water leaked from rusty faucets and tarps flapped against broken windows. Overhead the skylights hung in brittle shards where a hailstorm had smashed the glass several months before. Artists used the materials on site to create works, which they then installed in a variety of strategies. Black created a still life installation under a trip light that flashed on when someone walked passed. Mike Schuh composed a series of on-site sculptures, where he repositioned certain objects in combination with one another, almost like the stacks of rocks you find on a hiking trail. However, you couldn’t really tell what objects he’d organized together, and what objects happened to be that way before, or after his intervention. “Nothing I did for [Part One] is identifiable,” Schuh said about these works, “because it was intentionally done in such a way that I could not recall what I did and therefore could not share it with anyone.” Since objects were constantly getting moved around over the course of day’s work, what sculptures Schuh did create could have been moved before Part One even opened. Laura Davis salvaged a series of foam rectangle packaging and installed them like plinths on an upper mezzanine. Baker constructed roving paper sculptures that clung to the wall like dense and colorful webs. In all of this, Lund successfully used the warehouse as a frame; the viewer had to walk through that site and actively decipher works of art from what might otherwise be considered trash. The whole context, meanwhile, pointed to a greater network of economic production, especially what remains unsold and eventually becomes useless.

Lund has since invited his artists to recreate the show again, in a new site. Jillian Soto and Heather Mekkelson were added to the group. Soto collaborated with Black and Mekkelson interviewed those who visited the first Two Histories of the World, recording their observations. Through this new constellation of objects, something of the William H. Cooper Mfg warehouse has been translated for Hyde Park. In that translation something essential is lost while a new aspect (what was perhaps dormant in Part One) comes into view. Lund describes this second revival as “a new show made of absent works conjured up again.”

“Two Histories of the World: Part One.” Laura Davis, mixed media installation, William H. Cooper Mfg., 2012. Photo by Caroline Picard.

Echoes of those first works are certainly present at Hyde Park. Black goes so far as to quote her first piece directly with a rack of postcard photographs that feature her original trip-light installation: as a memento or souvenir; a nostalgic remembrance of the past. Schuh videoed himself creating his original sculptures on-site in the warehouse; he pulled the audio track from that video and made a vinyl record. The video at Hyde Park shows him playing and manipulating that record. Its jostling, unsteady frame underlines the past’s inescapable distance, it can never be recreated entirely, only conjured as a figment in the imagination. One might imagine that both iterations of Davis’ cubes are translations of the same original sentence. The “sentence” looked like one thing in a warehouse, and another in an art center. In tandem they point to a larger meaning outside of their respective contexts (or, if you will, “pages”). There is also an evident grasping, a desire to reach into the past and pull something from it.

Part Two obviously feels very different. Nevertheless there is a direct bridge between both scenarios. The objects at the Hyde Park Art Center appear to be waiting, as if for a yard sale, and perhaps in the same way they seemed to wait in that warehouse. These objects cannot shake their uselessness. And yet for that reason, they become enigmatic and inaccessible. These things point directly back to their past — to an elsewhere that is out-of-view. “What is seen through this virtual window is the out-of-field that is attached to what is inside the frame.” In his essay, Modes of Exhibition as Mediated Space: Projection Installation as Spectatorial Frame, Jungmin Lee points out that every exhibition has a frame. The frame of an installation is similar to that of a painting except that a viewer can actually enter the installation. At Hyde Park, one could say the William H. Cooper Mfg is out-of-view, but nevertheless active and present. Everything at the Hyde Park Art Center points to it. In pointing to that site of origin, the viewer becomes a participant. “Installation shifts consumers of culture from being spectators to being actors. The rigid structure and identity of cultural production are, in turn, fractured by the participation of members of the public as actors in a common symbolic action.”

“Two Histories of the World: Part One.” Suspected Mike Schuh installation, William H. Cooper Mfg., 2012. Photo by Caroline Picard.

While Lee spends the majority of his time talking about the way a frame operates in Rirkrit Tiravanija’s fleeting installation, Community Cinema for a Quiet Intersection, Two Histories of the World offers a similar opportunity. Except in this case, the relational possibilities lie between objects rather than people. “Installation instantiates perceptual shifts and invokes an alternative mode of social engagement of the self with the other, and even with the others within the self. Installation embodies a ‘sensorium of possible selves.’” I would argue that part of what remains so enigmatic about the work in Two Histories of the World Part Two is precisely what felt so curious about Part One, that is, the objects seem to have a life of their own. Obviously, they were manufactured by humankind, however, these things live on the periphery of human life. Their material legitimacy cannot be denied (they are tactile and occupy space) and yet they no longer fulfill the human functions they were once intended for. That potential has never been fulfilled, nor was it ever exhausted; still they fulfill themselves. One might even call these things smug, or self-possessed. That is something that has not changed according to the site of this exhibition. To try and better understand these objects, I want to apply Graham Harman’s object oriented ontology: to imagine these things possess their own autonomous being, even if it is not entirely accessible to me. They have not fulfilled their potential as human objects, but nevertheless do so in their own right, and on their own terms. These assembled objects seem absurd in the context of a warehouse (whose sole purpose is to house them indefinitely), or in an art center that cannot wholly elevate these everyday things to the status of Art Object. Consequently, one is forced to examine the relational possibilities between the objects themselves, and concede that they are at once pointing to a past — the life in the warehouse, the systems of production from which they were born — while nevertheless withholding those peculiar, embodied experiences.

You can read about my first impressions of Two Histories of the World Part One here.

“Two Histories of the World: Part Two,” Sara Black and Jillian Soto, mixed media. Installation view, Hyde Park Art Center, 2012. Photo by Caroline Picard.

Pingback: Two Histories of the World Part Two | The Lantern Daily

Pingback: Fall 2012 Activities, Events, Trips, etc. « Sculpture: Materials Lab