Lin Tianmiao. “Bound and Unbound”, 1997. Dimensions variable (detail). White cotton thread, 548 household objects, video projection, sound. Courtesy Asia Society Museum.

As one of the few female Chinese artists to emerge from the generation born in the 1960s and to come of age during the Cultural Revolution, Lin Tianmiao’s rise to international prominence in 1990s is in itself significant. The current exhibition of Lin’s work at the Asia Society Museum in New York—her first major solo exhibition in the United States—confirms that her status as an important artistic voice within Chinese contemporary art is indeed warranted. “Bound Unbound: Lin Tianmiao” traces the arc of Lin’s career from the mid-1990s, foregounding a body of work that addresses a broad set of concerns that range from gender roles to personal and cultural identity in post-Tiananmen China.

The mixed-media installation that gives this exhibition its title, Bound and Unbound, is among the earliest on view, dating from 1997. First shown in Beijing at a time when installation art was rarely seen in and often banned from state-run museums, Bound and Unbound consists of 548 household objects strewn across the gallery floor. Off to one side hangs a scrim with a video projected upon it. The objects on the floor are all wrapped cocoon-like in white cotton thread, a signature technique of Lin’s that she calls thread winding, where she winds silk or cotton thread tightly around an object until it is completely enveloped. Close inspection yields the identity of many of these cocooned objects scattered around the room: pots and pans, woks, teapots, toys, various drinking vessels and a sewing machine.

Lin Tianmiao. “Bound and Unbound”, 1997. Dimensions variable (detail). White cotton thread, 548 household objects, video projection, sound. Courtesy Asia Society Museum.

As noted in the informational wall text, one of Lin’s earliest and clearest childhood memories is that of her helping her mother sew clothing for their family. Lin, who was born in Taiyuan, in Shanxi Province in 1961, went on to become a textile designer. She and her husband, the video artist Wang Gongxin, would spend several years in exile in New York, repatriating in the mid-1990s after Tiananmen and settling in Beijing. But if the origins of Bound and Unbound are found in Lin’s childhood recollections and her earlier career in textiles, the installation’s eerie tone suggests that this assemblage of objects is not solely in the service of some romantic reconstruction of the past. Indeed, while the array of cocooned objects littering the exhibition floor takes on a decidedly oneiric tone, the uneasy atmosphere that pervades the room undercuts the prospect that the installation might be a wistful remembrance of times past. In enveloping these objects in thread, Lin has transformed utilitarian items traditionally associated with humble domestic life into objects that summon poetic and unconscious associations, but they are associations permeated with a sense of desolation and loss.

Lin’s mundane objects and their unusual presentation seem freighted with cryptic symbolic associations, collectively functioning as some sort of silent monument to a lost time and history. Their evocation of funerary objects summons thoughts about the deleterious effects of time, and their uniform treatment with thread creates a tension between individuality and sameness that takes on particular significance in the context of the Cultural Revolution that defined Lin’s youth and recent Chinese history. The array of woks and simple drinking vessels becomes a quiet yet psychologically charged testament to the rapid political, social and economic transformations that have reshaped a rapidly modernizing China, and to the upheavals in domestic life, social convention and tradition.

Lin Tianmiao and Wang GongXin. “Here? Or There?”, 2002 (detail). Fiberglass, fabric, thread, mixed media. Courtesy Asia Society Museum and Galerie Lelong.

An engagement with the turbulent changes that have impacted life in China over the past several decades is more obviously evident in Lin’s Here? Or There? (2002), an ambitious installation that the artist created in collaboration with her husband, in which haunting figural sculptures, their faces veiled and their bodies disfigured by accumulations of thread and fabric, stand like ghostly sentinels before video projections of serene pastoral views abruptly punctuated by footage of the noise and imagery of modern urban environments.

But unlike the clear message in Lin’s Here? Or There?, the video accompanying Bound and Unbound only heightens the ambiguity of the work’s overall meaning. Bound and Unbound’s video is a close-up of a hand cutting thread with a pair of scissors, which has been projected onto a screen made of thread hanging from the ceiling. The snipping sound made by the shears pervades the room; it is decisive and rhythmic, but its symbolic effect is unclear. It could be read as a provocative and liberating gesture, which would support a reading of the installation as a meditation on the female experience in China and a transgressive commentary on traditional gender roles (calling to mind Martha Rosler’s iconic film from 1975, Semiotics of the Kitchen). Alternatively, the cutting scissors could signal an incisive break with the oppressive systems and traditions of the past, or it may also function as an ominous and even threatening reminder of authoritarian attitudes. No definitive resolution is forthcoming, but in the context of the flux of post-Cultural Revolution and post-Tiananmen China perhaps the answer is meant to remain uncertain.

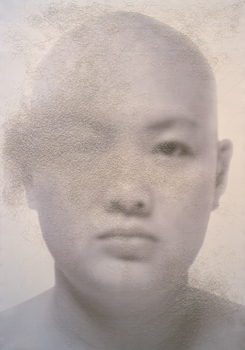

In Focus (2001), Lin explores issues of individual and cultural identity and forms of remembrance within the context of recent Chinese history more forcefully, if still somewhat obliquely. Focus is one of a series of works—perhaps her best known—in which the artist transferred black and white images of herself, her family and friends onto canvas. Lin then embroidered or sewed thread onto the surface of the larger than life-size portraits, often obscuring part of the sitter’s face.

Lin Tianmiao. “Focus,” 2001. Digital C-Type print on canvas, hair, silk threads, cotton threads, 95 1/4 x 5 x 69 3/4 inches. Courtesy Asia Society Museum.

Portraits carry particular weight in China given that during the Cultural Revolution, portraits of Chairman Mao Zedong were not only ubiquitous but the only ones permitted. Lin’s embroidery of the work’s surface instills a sense of intimacy and uniqueness to the work, offsetting the detached, bureaucratic austerity of Lin’s self-portrait, which has the stark frontal appearance of a mug shot. But the embroidery also obscures, thereby creating a tension between the thread as restorative device and occlusive object, transforming the portrait into a meditation on the memories, identities and histories lost or transformed by Mao’s reign, and to the ongoing effort to memorialize and reclaim them.

Lin’s thread winding proves less successful in some of the most recent works on view, including More or Less the Same (2011), in which she has wrapped macabre, hybrid objects made of synthetic human bones combined with utilitarian tools. While vaguely Surrealist, they lack the subversive spirit, fantastical imagery and discomfiting energy found in earlier works. But it is her haunting early works that affirm Lin’s status as one of the important artistic voices to have emerged from China in the past twenty years, and which make “Bound Unbound: Lin Tianmiao” necessary viewing.

“Bound Unbound: Lin Tianmiao” is on view at the Asia Society Museum in New York until January 27, 2013.