[Ed. Note: The Art21 Blog is running a bit behind this week due to superstorm Sandy. Our thoughts are with everyone who has been impacted by this storm; we hope that all of you out there are safe, warm, and dry.]

This is a slightly delayed post due to Frankenstorm Sandy taking out Internet access for the past few days. My thoughts are with those who, like our family member who lives in Sheepshead Bay, had their home totaled, possessions lost, or power and sanity cut by the crazy weather.

This time two weeks ago I was in sunny Durham, North Carolina, for SECAC (the Southeastern College Art Conference) and I presented on a project I have shared on Art 21 before, Art History Teaching Resources (AHResources). I first began to conceptualize AHResources almost two years ago while speaking to my academic advisor at the Graduate Center and telling him how my first semester as a Graduate Teaching Fellow had gone. I think I used the phrases “baptism of fire,” “like jumping off a cliff,” “like bungee jumping – in both good and bad ways,” and “[expletive] Stokstad.” Teaching the art history survey certainly felt like a rite of passge somewhere in-between sweet sixteen and blood sacrifice.

My main concern was that, unlike at my previous place of work (the Guggenheim Museum), I hadn’t found any basic template or peer-to-peer platform for sharing teaching resources. I felt like I’d spent a semester reinventing a very linear wheel. I was searching for the conversations teachers of all levels have (or don’t get to have) around such issues as how we prepare to teach, what professional development we have (or don’t), what obstacles and frustrations we face in terms of implementing best teaching practices (and identifying these pratices), and what to do with the contentious beast that is the chronological art history survey. Now three years in, I realized that it’s not just newbie me. I have found that survey instructors are often teaching in the dark, isolated from opportunities to converse on this subject, afraid to ask for help for fear of seeming somehow incapable, or often just too time-strapped. Whether tenured or contingent teacher, it can be difficult to innovate and experiment with teaching the art history survey when so much else is demanded from our time. How often do we observe other teachers teach survey? Give constructive feedback to our peers? Have time to practice and refine class activities before debuting them?

Compounding this, a recent article in the Guardian hit home the fact that good teaching in the academy isn’t rewarded like it should be. Published books are. Published articles are. Yet innovative and dedicated teaching is not tenure portfolio material. The article pointed to this disregard for best teaching practice as part and parcel of gender disparity in the academy. The Guardian cites statistics that show that of those who hold the title of professor in UK institutions, only 20% are women, even though 45% of all academic staff are female. Per the article, “at the highest levels, the most senior management positions are judged on research output rather than teaching expertise and – for all the above reasons [see the full article] – women are likely to have done more of the latter.” Those highest on the work ladder, often men, are individuals who have focused on the old-school track of publishing and left the child rearing–both at home and in the classroom–to others. Those teachers of both genders who take the time to prioritze great teaching pratice? Silly them. The statistics reinforce the fact that focusing on good teaching is a time-suck that–generally–hobbles rather than helps us all up the career ladder.

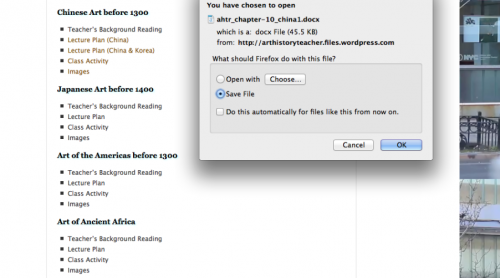

My first semesters in the classroom were a rude awakening in terms of managing expectations I had for myself as a teacher, and the expectations I had of my students, all of whom took the art history survey as a required class. But what I really struggled with was the content I was tasked with teaching, which was a global survey. My specialization is twentieth-century architecture and museums, not the Arts of Africa, or Asia, or even – as a Brit – the Arts of America. I felt like a total fraud. It was very different from my experience as an undergrad, where each segment had been taught by a specialist. It was also in stark distinction to my time at the Guggenheim, where monthly museum educator training in both pedagogy and content had been a mandatory part of teaching practice.

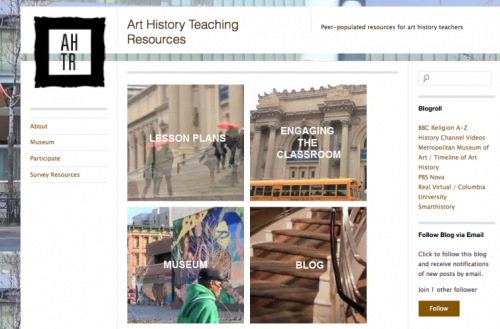

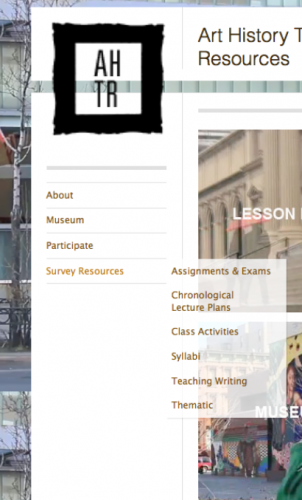

Cut to two years later, and I have almost finished building phase one of a website for sharing teaching resources. At SECAC, I co-chaired a panel titled The Museum and the Art History Survey Requirement with my colleague at Baruch College, Professor Karen Shelby, who has pioneered an awesome museum video project that the AHResources site will host. I shared my motivations for building the AHResources platform for art history survey teachers and my hopes for its final incarnation, and I got a lot of great feedback, critiques, suggestions, and questions. Last time I posted about this project on Art 21, I also got lots of great feedback for which I was truly grateful. One commenter suggested that this type of centralized resource was obsolete as there are so many resources already available online. While I agree that there are a range of materials already out there – from British Museum Director Neil MacGregor’s A History of the World in 100 Objects, to the truly awesome Smarthistory, and the Met Timeline of Art History, for a start – the culling of these resources into a thoughtful thematic lesson plan is what takes time, and what I want to short cut for time-short teachers. If we have access to a basic set of materials when we start out, we have more time to think about alternative teaching strategies. The lesson plans I have gathered so far gesture to many existing resources, including suggested short readings for students, at-home and in-class videos, and class activity templates. Other readers were more receptive to the idea of giving teachers basic tools. As one commenter pointed out, “so many of those who teach survey courses have no experience or training in teaching methods, a baffling irony of American higher education.” Another discussant rightly chided me for not doing more to support an interactive, participatory design process at this early stage, reminding me that any such platform should always work in “perpetual beta”–and so, more on this in a minute.

However, one comment really made me stop and consider what a great teaching resource should do, suggesting that by teaching survey at all “we’re doing our students a disservice … most of us seem to teach by the book, and little of us have the resources available to teach in a way that un-surveys and promotes deep learning and understanding by our students … I’ve rarely experienced innovative pedagogy– even our [graduate] programs place great emphasis on the survey model in order to prepare us for our many slide identification exams. We should forget about teaching whole cultures, it’s insulting and wrong.” I began to realize that the model I had built thus far still largely hewed to the traditional survey chapter divisions. What model might be more open-ended? What might happen if the images we look at chronologically in Stokstad might be pulled apart and offered to the instructor in different clusters (another great suggestion given to me via feedback)? What would happen if other images were swapped in instead, the vernacular and the local augmenting or replacing the canonical? What would happen if a dancer, or a mathematician, or an anthropologist made the content choices instead of someone like me, raised on the art history canon?

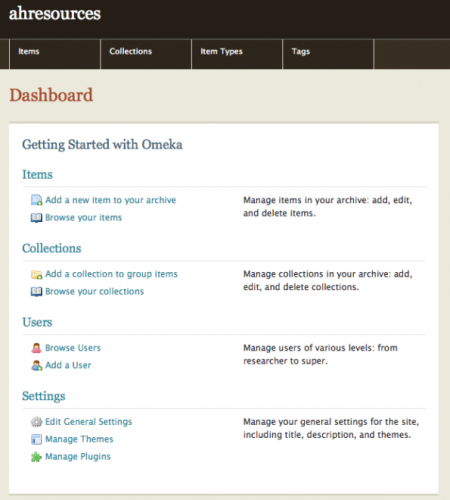

To that end, I have just begun to work with a new program, Omeka, which will take the images, lesson plans, class activities, and other materials I have gathered so far and enter them into a database as separate entities. It’s a system much like those used in museum collections to store the information of every object and the associated research undertaken around the object. This will allow the current survey materials and–key to exploding the canon–other materials and resources contributing teachers would like to add, to be tagged in multiple ways in order to make a searchable collection that can be sifted through thematically as well as chronologically. A first-time teacher can still find a lesson plan on the Arts of Africa, but instructors can also search, for example, under “animism” and link a crocodile toguna hut in Mali to a Shinto shrine in Japan.

The project I outline above is still in progress, and is one beginner’s theoretical exploration as much as a practical project. As I see it, a resource like this has to tread the fine line between shying away from prescribing the Stokstad canon, and actually being of use to really new teachers who have little clue what to do in their first few semesters at the lectern. Innovative teaching methods can be hard to imagine and implement at the beginning of a career as a teacher–and, as I have heard at SECAC, also difficult when teaching as the lone art historian in a small department, or when totally overloaded, or after following the same plan for many years. I would suggest that having the confidence to shatter the template comes after having a template in the first place. Leading a great classroom discussion often requires a really well-prepped template.

The most important result of the panel Karen and I hosted at SECAC is that we were approached by those whose curiosity was piqued enough to offer themselves as beta testers, interested in sifting through the site, classroom-testing Karen’s museum video project, and adding their own materials. If you’d like to beta test the site with us, or know someone about to start teaching survey soon (or in their first year or two), please get in touch at [email protected]. I want to say thank you to the New Media Lab at the CUNY Graduate Center for supporting my project, to Dan Shields for brainstorming Omeka with me, and to Karen Shelby for many conversations about how our projects could mutually support each other for the benefit of teachers and students alike. Hopefully this site will offer something useful, not least the opportunity to simply see other models and share with peers. Heck, if models like these could save us time on teaching prep and give us more time to negotiate the tricky career ladder, publishing, research, and gender disparity, then sharing resources becomes not just personal but political.

Pingback: Debuting arthistoryteachingresources.org on Art21 | Michelle Millar Fisher

Pingback: What Inspires Your Museum-Based Teaching? | Art History Teaching Resources