Coincidentally, I was bound for Chicago the day after celebrating the results of our presidential election. Charged with the energy of President Obama’s acceptance speech on Tuesday evening, I came to the city to prepare for an upcoming show and have continued to mull over his words. With a slight shift in context, I realize that the language of art and the language of politics are not so far from each other.

“I have always believed that hope is the stubborn thing inside us that insists, despite all evidence to the contrary, that something better awaits us so long as we have the courage to keep reading, keep working, to keep fighting.” –President Barack Obama

Last month in New York, Creative Time held their fourth annual summit on the current state of artistic activism. I’d heard rumblings about the summit, but little more. It was during a recent William Powhida lecture that the topic resurfaced and I began to investigate the concept of activism in this realm and learn how it could also inform my practice.

In his talk, Powhida referenced a letter from Stephen Duncombe and Steve Lambert, co-directors of the Center for Artistic Activism. After participating in the 2012 Creative Time Summit, Duncombe and Lambert published an Open Letter to Critics Writing About Political Art. They released the letter in an effort to address the lack of vocabulary and meaningful critique in this area, a gap illuminated during this year’s summit. What I found most interesting was the investigation and dissection of its very definition, clarifying that “art about politics is not necessarily political art.” Its primary function, rather, is to challenge and change the world. Beyond using social injustice and political struggle as mere subject matter, political art moves beyond representation of the world to act within it.

Referencing political art’s engagement with the world, they encourage an acceptance of its messy nature. Embracing less traditional venues, certain elements are out of the artist’s control. But in contrast to the diluting effect of compromise for the traditional artist, compromise for the political artist is “the very essence of democratic engagement.” Ultimately, Duncombe and Lambert argue that the power of art “lies in its ability to open up a space to ask questions rather than deliver answers.” In their minds, this approach creates a solid foundation for politics as well.

Returning to the words of President Obama’s acceptance speech, similar themes emerge. As citizens in a Democratic nation of 300 million people, he recognizes that the political process is noisy, messy and complicated. There are the battling egos and special interest groups. There is passion and controversy. But there is also the undeniable strength of our liberty, and our ability to engage. As artists, this means exercising our rights as citizens, in whatever way we feel that necessary.

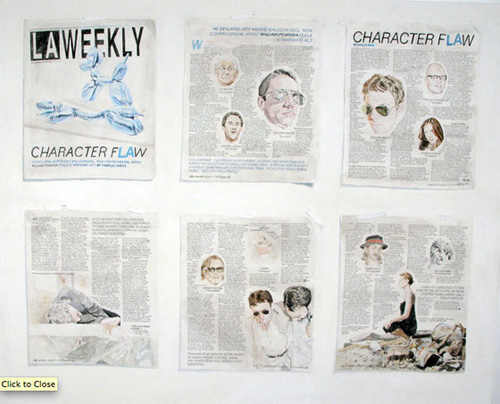

As a visual artist based in Brooklyn, the work of William Powhida revolves largely around a critique of the contemporary art industry. In response to his observations of the art world, he creates “art criticism” in graphic form. Using his trompe l’oeil painting and drawings on paper emulating notes, letters, enemies lists, rants, and to-do lists, the artist develops a fictional artistic personality which critiques, insults, complains, and articulates life as a contemporary artist in a market-driven economy.

This lecture coincided with my return to Cranbrook; it was the first time I had spent real time back since graduating from the Academy in 2011. I had returned to do some work at Vessel & Page, a nearby gallery providing a liaison between the Academy of Art and the greater community through a calendar of exhibitions and events integrating the work of alumni and local artists. As part of my residency, I prepared an artist lecture to be presented during an open studio event. Thinking about the quieter approach of my own work and its engagement with place, I considered my own politics. How do the subtleties of this work deliver their own types of political beliefs? As we move forward in our careers and formally speak about our work on a more regular basis, how are these framed?

I return to Obama’s declaration of hope as “the stubborn thing inside us that insists.” At the base level, perhaps what the pursuit of art and politics share is that desire to keep reaching, to keep fighting. It is the aim to continue building and dissecting our own work, sharing the complexities of our practice with others in the process. It’s not necessarily about delivering the answers so much as presenting the questions, as Duncombe and Lambert would agree. By investing our beliefs in the act of making, and staying the course when the odds are against us, that stubbornness is what keeps us afloat.