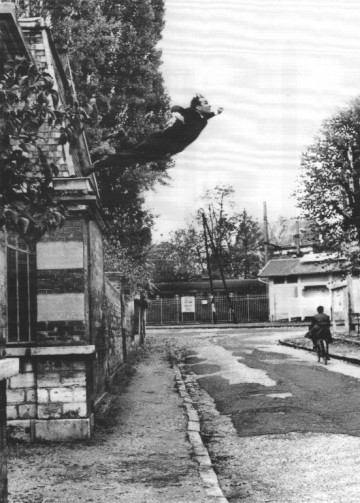

Yves Klein. “Le Saut dans le Vide (Leap into the Void).” Photomontage by Shunk Kender of a performance by Yves Klein at Rue Gentil-Bernard, Fontenay-aux-Roses, October 1960.

Can art help us to understand and negotiate space? The question comes in part from considering the relationship between art and architecture, and in part from the idea that you are continually learning to see. Given this framework, and without attempting to ponder the theory of knowledge or epistemology, I began thinking about the notion of the void in art, which in my estimation, rather than empty space, can amount to a visual description of some alternative dimension of space, time, or perception. Experiencing a void is a way of acknowledging new possibilities, or learning to see space in new ways.

Consider, for example, the work of James Turrell, which uses light or the absence of light to describe one’s existence at the moment of viewing, and offers a very distinct and precise experience of space that lies apart from mundane daily movements and thoughts. In some ways, this also makes it possible to grasp the elements of a seemingly arbitrary or empty space, or an abstract condition, and understand it as actually tangible, here and now. Translated in utilitarian terms, this could be an effective way to “get out of your head” and feel a connection with the space you inhabit. It could also serve to introduce “negotiability”: the idea that a space can change depending on input and engagement, a process often made readily apparent by the changing nature of light.

But it’s not just site-specific, light-dependant works such as these that could transform our understanding of space. Markers of space exist in more visually complicated works of painting and sculpture as well, and are elements that can effectively challenge our perceptions of depth and distance by offering illusions or obstacles on the path to perception. It seems obvious that having a heightened awareness of the space you inhabit would allow for a more enhanced experience, but to go a bit further, how does awareness make us behave? How might it inform our approach to utility?

All of this musing is to say that I hypothesize that experiencing artworks that deal with space in this way should somehow teach us to navigate, or at least understand, our built environment in a more sophisticated way: perhaps to become more aware of the sublime in the aforementioned mundane, to decipher illusion more adeptly, or to think of scale and proportion in more inventive ways, among other things. To put the original question in more of a concrete context, would taking an artistic approach to architecture and design help us to achieve the goals of fluidity, harmony, and happiness that our buildings ideally would provide? How might it help us to understand our capabilities in creating formal relationships, and harnessing and using light? Finally, how might it help to inject humanity, the power of experience and memory inherent in art, into the built environment?

Big questions. Possibly too vast to be useful. Nevertheless, I am excited for the opportunity to examine a few pieces of architecture, art and ideas that might help illuminate or at least refine some of them. At this stage I am (sometimes woefully, sometimes blissfully) under-equipped in terms of the reserves of history and philosophy that I have to draw on, so my observations will likely depend primarily upon my own visual experiences. They will serve to record my attempts to understand and talk about works of art that undertake a challenging view of space, in hopes that they can help explain some aspects of our experience in the broader built environment.