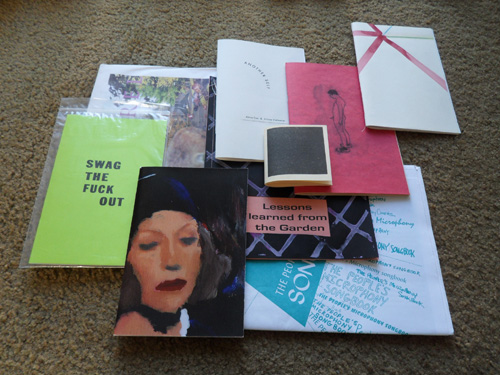

A selection of recent zines by Los Angeles artists. Authors clockwise from left: Keith Rocka Knittel, Christopher Russell, Anna Mayer and Laura Aldridge, Akina Cox and Ariane Vielmetter, Akina Cox, Christopher Russell, Akina Cox, Elana Mann, Christopher Russell. Photo: Carol Cheh.

American zine culture seemed to reach critical mass in the 1990s, when self-published pamphlets and journals of every conceivable stripe proliferated in underground communities throughout the country. Both a product and a progenitor of DIY culture, which was flourishing in response to the advent of corporate mass media, zines provided an uncensored, unregulated, and unsponsored outlet for personal expression, which encompassed everything from homegrown thrift store tips and day job horror stories to the birth of the influential riot grrrl movement. It seemed that everyone was making and reading zines, so much so that alternative periodicals like RE/Search and Factsheet Five published popular zine guides and directories that are still in print today.

I hadn’t really thought about zines too much since my days of living in San Francisco, when I was an avid reader of Rollerderby, Mudflap, and I Hate Brenda, among other gems, and even did a one-off, I Scare Myself, in collaboration with my old friend, the music journalist Kimberly Chun. For me, zines seemed almost emblematic of a certain moment in the indie culture time/space continuum. But then a funny thing happened—artists I know here in LA started sending me zines, one after another. Some were documents of recent projects, others were discreet art projects in themselves. Curious, I put out a call on Facebook to see if anyone else wanted to share their zines with me, and promptly found myself deluged with offers and tips. Were zines back? Or had they always been there, and I just hadn’t been paying enough attention? And how were the zines of today different from the zines of my youth?

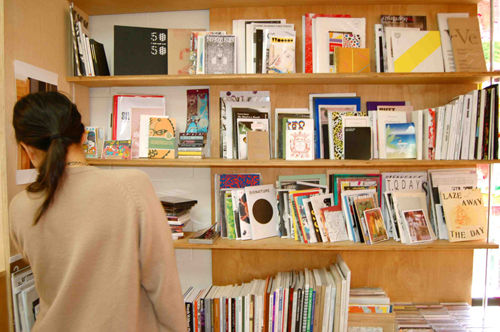

Proprietor Wendy Yao tends to the shelves of zines at Ooga Booga Store in Chinatown.

Photo: Kenza Chaouai, via heartymagazine.com.

To answer these questions I had to consult someone who’d had a deeper and more consistent history of engagement with zine culture than I did. So I phoned up Wendy Yao, the proprietor of Chinatown’s Ooga Booga Store, which is known for carrying a large selection of local and international zines and artists’ books, among other wares. As a teenager in the 1990s, Yao had co-founded an early riot grrl band called Emily’s Sassy Lime with her sister Amy and their friend Emily Ryan; since then, she has maintained steady connections with DIY culture through various music and art related projects. I asked her for her thoughts on how zines have evolved since the 90s, and what the relationship is between zines and the visual art world.

“There’s definitely been a lot of evolution,” Yao said. “In the 90s it was very much about DIY culture and modest productions, but now you actually have zine publishing companies like Nieves that will carry your work. Also, there are a ton of artists’ zines coming out now, and that was not the case even eight years ago when I started Ooga Booga. Zines in the 90s were very much oriented around specific discussions of music or politics, or they were diaristic rants. Of course there were zines dealing with culture and art might have been included in those, but you did not see the kind of art zines you are seeing now, not even coming out of art schools.”

We both mused on how there had been a long history of artists’ books that dated back to the early twentieth century, and some of them had taken zine-like forms. I remarked that the current surge in artist-made zines seemed to represent an intersection between the lineage of artists’ books and that of underground self-publishing. Yao concurred and reflected: “Johanna Fateman, who co-founded the band Le Tigre, went to art school and used to do a bunch of zines with art-related themes. But even those were more discussion-oriented in the vein of the punk fanzines—they served the same purpose that I guess blogs do now. Maybe blogs have taken the place of zines in that regard. Zines are handmade after all—it’s natural to think of them more as art objects than just as tools for getting the word out.”

LA Zine Fest and Rookie Mag zine workshop at Meltdown Comics. Photo: Meredith Wallace, via LA Zine Fest Flickr pool.

To get some additional perspective, I decided to also check in with two of the organizers of the new LA Zine Fest, whose first big event this past February was a huge success. They hold periodic zine workshops during the year, and are now planning for their second festival in February 2013. I asked them for their take on the broader zine scene in Los Angeles, and found that their insights roughly dovetailed with Yao’s. “Zines are resurfacing from the underground, and it’s not uncommon to find a well-stocked zine section in local independent bookstores around town,” said Meredith Wallace. “I think that traditional means of success is harder to come by these days, and so people are investing more time and effort into their creative passions again. With more and more people unemployed or underemployed, DIY publishing is an attractive and affordable medium to promote one’s creative exploits.”

Bianca Barragan added the following comments on the historical arc of the LA zine scene: “An important trend I’ve seen is that zines have become increasingly visual. Illustration, comics, photography—these were always present in the zine world, but in LA, it seems like they are sort of enjoying a uptick in attention. Zines used to be these super-personal, super-political publications. My favorites were ‘perzines’ that made you feel like you were reading somebody’s diary or a note you got passed in class. I don’t see a whole lot of these anymore, but maybe I’m just looking in the wrong places! In LA at least, there’s of course a rich history of punk zines like Flipside and Slash, but there was a big-time explosion and appreciation for zines and their potential for illustrators and comics in the Asian-American community, something that Giant Robot famously encapsulated. My best friend is Filipina and growing up, to see stuff like that—it was awesome, like looking into a secret world. That’s what zines were always about, and something that continues to this day.”

Next month: a closer look at several of LA’s artist-made zines.

Pingback: LA Art Book Fair’s press coverage 2013 | fireplace chats

Pingback: Naptime Comics + mail call! | breakfast in the bay window