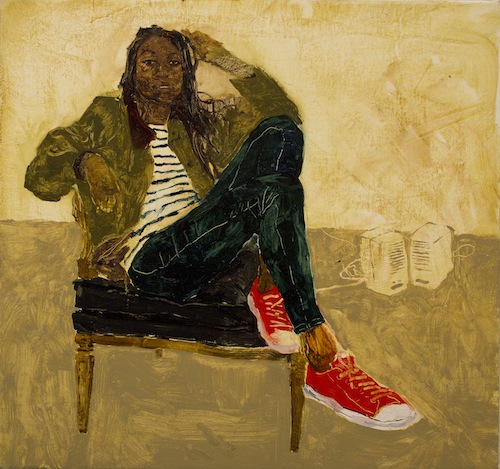

Cullen Washington, Jr. “Caped Crusader,” 2011. Mixed media on canvas, 100 x 77 in. Courtesy the artist, cwashingtonstudio.com.

Fore, the fourth exhibition in The Studio Museum in Harlem’s “F” series, brings together twenty-nine young emerging artists of African descent born between 1971 and 1987, working across the United States, in painting, performance, photography, video, assemblage, and sculpture, with many of the artists crossing media within their own practices. The energy in the show reflects the curatorial endeavor, a collaboration of the Museum’s three curators: Lauren Haynes, Naima J. Keith, and Thomas J. Lax, each with divergent interests and areas of focus. Through cross-country studio visits and extensive discussion, they’ve created an exhibition that feels nuanced and layered, with the works pulling from multiple art historical traditions and lineages, pop-culture references, black culture and history, regional histories, social, political, and individual concerns, competing narratives, new media. Nowhere is curatorial discernment and vision more explicit than in a group show of emerging artists, and Fore demonstrates it, presenting a selection of artists that open possibilities and new channels of thought.

Performance feels very present in Fore, filmed and digitized performance, as well as live. In conjunction with the exhibition, the Studio Museum will also host PerFOREmance, two three-day performance series in December and February, to present new and commissioned work. At the opening, Jacolby Satterwhite, whose work I always find compelling and difficult to categorize, was performing Reifying Desire: Model It (2012), a live and two-channel video installation, emphasizing the tension between real and virtual space. In a silver body suit and headpiece, Satterwhite posed on a low, white platform, while behind himself, on screen, he performed choreographed moves for another intrigued passing audience on the street, and in front of a series of outrageous “natural” backdrops, destructively swinging a rope-like braid on top of his head, or gyrating in front of retreating space.

Satterwhite has full-range play with simulacra. He brings the oddly anachronistic, the sci-fi, the 3-D animation, the body suits, the way the future was envisioned by the past, into the present, through the immediacy of performance. The line between “performer” and person is repeatedly crossed—his work has an approachable, open quality, and he often incorporates the personal (floating through digital screens, sometimes on his own body, are drawings by his mother made during her struggles with mental illness). It’s fascinatingly suggestive of how we’re living now, in a multisensory, layered, representational, and digitized way. The future, as Satterwhite suggests, seems not so much a place we will arrive at, but the opening of a new portal of perception into our present.

Jacolby Satterwhite. “Reifying Desire: Model It” (video still), 2012. Two-channel video installation, painted wooden platform, spandex catsuit, and live performance; 6:28, color, sound, 10:32, color, sound. Courtesy the artist and Monya Rowe Gallery, New York.

Visually separate in the Museum’s first-floor gallery, Taisha Paggett was enacting Decomposition of a Continuous Whole (2012). Blindfolded, she methodically works her way across the wall with an oil pastel, in a choreographed score that corresponds to a list of written cues on the gallery wall: “arc sink,” “forward high circle,” “dot.” A dance artist, Paggett’s movements, and the synesthesia in the undertaking, is mesmerizing, beautiful, and discomfiting to watch. The work recalls Carolee Schneemann’s performance from the 1970s, and is interrogating the performing arts canon, and who is visible within it. Next to it is Nate Young’s Closing No.1 (2012), a church pew facing a blank wall with a pair of headphones. Through them, a man is delivering an impassioned sermon on painting in the rhetorical tones of a preacher. Art, it suggests, asks the same devotional intensity of its acolytes, the sacrifices and the fated leap the unknown. It’s an inspired installation decision. While sitting in the pew, out of the corner of your eye, you see Paggett move in and out of sight along the adjoining wall, the physical manifestation of this very human and yet transformative, spiritual force.

In the area of painting, Jennifer Packer’s series of portraits done in loose Impressionist brushstrokes, of friends, classmates, and family members in repose, investigate the tradition of portraiture, and our expectations from it. (Packer, along with Cullen Washington, Jr. and Steffani Jemison are the Studio Museum’s artists in residence for 2012–13). Toyin Odutola’s supremely intricate portraits in marker and ballpoint over color wash, trace the musculature and reflective surfaces of the face and body, questioning “black” as a color and a concept. Sienna Shields contributes several large-scale, intoxicating collages, a chromatic remapping as finely shaded as paint. Her work recalls the tradition of collage, strong at the Studio Museum, with Romare Bearden’s presence in its founding, in the permanent collection, and as an inspiration for the Museum’s city-wide show, The Bearden Project, organized by Haynes. The past also emerges in Zachary Fabri’s 16mm film Forget me not, as my tether is clipped (2012), an elegy to the ten years the artist spent living in Harlem, and a meditation on letting go of it.

What makes something feel truly new? I was thinking about this while staring at Cullen Washington, Jr.’s Caped Crusader (2011). Washington’s mixed-media works on canvas are layered, physically and symbolically, with cultural references, words divorced from their signifiers, remnants and visual markers of cities, and memories of cities. He has a sensitivity to how experience has materiality to it, a texture, that corresponds to the physical elements in our environments and the tactile way we process the world. Experiences are not only cumulative, they are also freighted with nostalgia and desire and dreams, subject to personal and collective histories, which appear in partial or submerged forms. In Caped Crusader this layered expressiveness rises over a T-Mobile sign like an information cloud. It says so much about the way we communicate now, as new and varied as the methods of communication feel. There’s a massive subtext to discourse, to language, that will always exist. It is the land around words, “land before words,” as Washington says of his own artistic process—an experience that precedes the language he has to describe it. It is this awareness and integration of that space, the many meanings of “before,” that makes this show feel as if it is articulating something very forward thinking.

Fore is on through March 10, 2013, at The Studio Museum in Harlem. PerFOREmance will be held December 13–15 and in February 2013.

I welcome thoughts, ideas, show announcements. Please email me at [email protected].