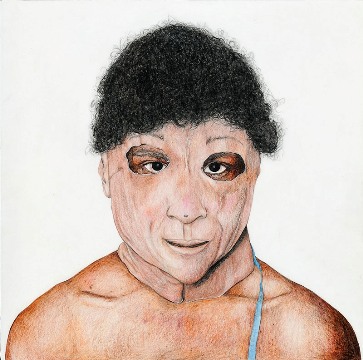

Desirée Holman. Television (Conduits of Fantasy) 1, 2007. Color pencil on paper, 16 x 16 in. Courtesy the artist.

As a family we watched television. We watched during dark afternoons with the blinds closed and on summer evenings with the doors open. We watched during dinner and on afternoons and sometimes late into the night. We watched on a large television set downstairs with a pirated cable box on top and on two small sets upstairs, one in my parents’ bedroom, another hidden in a cupboard in the living room. We did not discriminate: game shows, golf tournaments, detective shows, sci-fi, sitcoms, and slapstick played across the various screens.

Bill Cosby as Cliff Huxtable on The Cosby Show.

Of all the shows we watched, sitcoms affected me the most. I could see myself and my family in their anesthetized versions of daily life and longings: in Cliff Huxtable’s penchant for hoagie sandwiches, in Mallory Keaton’s superficial preoccupations, in the Brady siblings’ rivalries. But I also didn’t recognize us: the jokes were too funny, the clothes too stylish, the conflicts less enduring. A foreign element persisted; enough was unfamiliar for the shows to function as an escape. As a family, we watched these onscreen families, not always certain which of us was real and which was imagined.

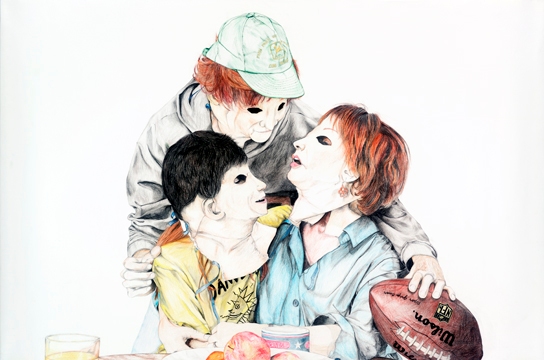

Desirée Holman. At the Park with Football, 2007. Color pencil on paper, 24 x 36 in. Courtesy the artist

Named for a 1939 ad campaign for TVs, Desirée Holman’s The Magic Window (2007) captures the ease with which we project ourselves onto television characters and the inherent folly of such an act. In Oakland-based Holman’s series of drawings and a three-channel video, individuals depict characters from The Cosby Show and Roseanne, as they frolic and act out family charades. Their portrayals are deliberately unconvincing. Their masks are baggy and crude. Eye sockets are too large, necks are unfitted, proportions are all wrong. Real hair spills out from beneath the coverings; actual eyebrows peek through.

Desirée Holman. Not Cliff (Conduits of Fantasy) 1, 2007. Color pencil on paper, 16 x 16 in. Courtesy the artist.

Desirée Holman. At the Kitchen Table with Football, 2007. Color pencil on paper, 24 x 36 in. Courtesy the artist.

Faces turn monstrous as sitcom icons become hollow zombies, perhaps their true identities all along. Here masks reveal, rather than conceal, real identities. In their implausibility, the ill-fitting faces mirror the discord between sitcom reality and reality—the former will never be the same size as the latter, no matter how many times we try it on.

Alf: the personification of suppressed difference in suburban life. No matter how he tries, he’ll never fit in.

Nuclear family life can be an alienating affair. Members are inserted into predetermined roles, forced into emotional intimacy, expected to conform. The pressure to assimilate can cause mutations and twisted outcomes. Shows like ALF, in which a furry alien infiltrates an otherwise conventional suburban family, give form to the difference suppressed within family life. The Magic Window achieves something similar, turning our desire for a uniform and idealized world into a grotesque pantomime that doesn’t fool anyone.